Craftsman in struggling Egypt ‘a man with two souls’

The promise of the revolution has shriveled along with the economy, turning a Cairo goldsmith into an iceman with little hope for his future and the nation’s.

- Share via

"What do you want to write about?" asked the iceman.

He glanced down the alley. A cat dashed over his damp feet.

"The poor?" He thought for a moment. His eyebrows arched. What about the story of a goldsmith, a man who once made lockets, rings and bracelets? The iceman looked at his reddened hands, dirty clothes, ripped shoes. He wiped his forehead and spoke as if unspooling a riddle.

"I was a boy," he said. "My father took me to his friends who worked in gold. I made tea and coffee for them. I studied their craft. I grew. I worked for a goldsmith in a shop in Khan Khalili bazaar. I started selling my own creations on the side."

He swallowed.

The shop closed two years ago, the gold in his hands vanished.

"I had been known for one thing all my life," said Mohamed Gamal Mohamed. "But I've become someone else. I am a man with two souls."

He shut his eyes.

"Ice," he whispered, "was the only work I could find."

He stood in an alley outside the bazaar he knew so well. It was hushed. Paperweight pyramids, onyx pharaohs, tin and copper trinkets shone in the sun. All for sale, but nothing selling; the tourist crowds have thinned since the 2011 revolution that overthrew Hosni Mubarak, turning craftsmen into desperate men, their families destitute.

"These are shabby times," said Mohamed Ibrahim, a carpenter with a workshop down the alley from the iceman. He tapped his chisel; wood curls blossomed and blew away. Eighty percent of his business has disappeared. "This is not the way to bring back the Egypt that once was."

What once was here is often more imagined than real. But the man many believe will set the nation right looks down from a banner hanging in the alley: Gen. Abdel Fattah Sisi, commander of the armed forces, hat brim pulled tight, chest tinkling with medals. Ibrahim said Egypt needs a strong man such as the one who just brought down Islamist President Mohamed Morsi in a coup and crushed his Muslim Brotherhood movement.

The promise of the revolution — songs in the air and Mubarak slinking away in a helicopter — seems distant now. Gone like so much gold, the uprising that reshaped the Arab world has degenerated into a succession of military men, Islamists and ceaseless unrest.

The news that trickles through the alley is seldom good and the shopkeepers, once clever chameleons reflecting the sentiments of prevailing politics, don't bother anymore to mask their bitterness.

"Morsi told us things would get better, but he wasted Egypt's blood. He is not worth three pennies," said Ibrahim, rubbing thick hands over the smooth inlay of a chair back. "I fought in the 1973 war against Israel. It was a time of great patriotism. Sisi is full of that kind of nationalism. We need someone like that."

A poster of Gen. Abdel Fattah Sisi, commander of Egypt's armed forces, hangs in a Cairo alleyway. It reads: "A man for the Times."

The sun crept higher but barely pierced the narrow alley at the edge of the bazaar. The man selling Korans was half asleep; the butcher took off his apron and lodged a cleaver in his cutting block. Men argued politics over tea but no one at the tiny cafe had much of a tip for the boy waiter, who was on his own after leaving his village to earn money for his family.

"Someone has to pay attention to the poor man," said Ali Sokkar, stringing prayer beads with a needle in a nook just off the alley. "The poor man" he spoke of could have been any man in the alley or in any alley across this dusty, sweltering country, where almost half the people live on $2 or less a day.

"We need a new leader who is educated and far removed from religion," said Sokkar, whose wares are sold from glass cases in an upstairs room by a woman who turns on the air conditioner only when a customer enters. "The nation should be for everyone. Religion is for God."

"We didn't hate Morsi," he said. "We just wanted him to be fair. He failed. He only cared about the Islamists and the Brotherhood."

We didn't hate Morsi. We just wanted him to be fair. He failed."— Ali Sokkar, who strings prayer beads in Cairo

Men head to the mosques. Minarets, hazy in the heat, prick an ancient skyline that seems to float toward the Nile and the western desert. A woman carrying groceries leads her daughter home through the distant blare of car horns. A beggar roams through traffic.

The iceman knows every face in this kaleidoscope, especially the juice shop vendors, who buy most of the ice he hacks from blocks with a pick and mallet. He earns about $4.30 a day, a sum that reminds him of how far he and his nation have tumbled.

"I used to spend that much a day on tea and coffee for my gold customers," Mohamed said.

His father made folding tables all his life. The old man is retired but Mohamed can't help him much. No one knows what will happen next in Egypt. Mohamed thinks Sisi is "beautiful," but generals have lied before.

His wife told him she must find a job to help the family. He doesn't want that; it would be a mark of shame for a man who once impressed his bride's family with a pocketful of cash, an apartment and a few trinkets.

"Egypt has stopped. We're not going anywhere. Where is the future? Where is the money?" he said. "I have a wife and two small children. The only person living a good life in Egypt is the thief. He has no conscience. A man without a conscience will survive."

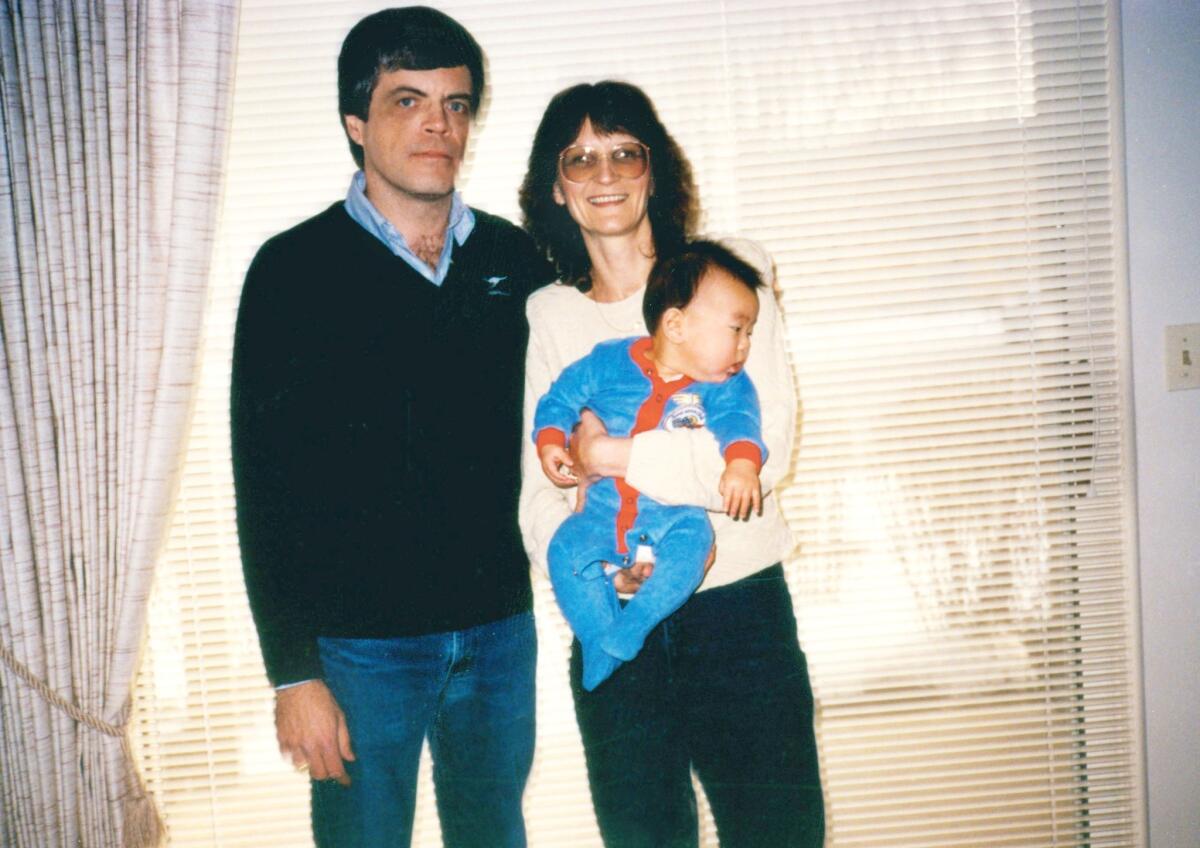

Mohamed Gamal Mohamed used to create pieces similar to those he points out in a shop not far from where he later sold ice.

Mohamed's hair is receding. His eyes are tired but bright; coils of gray gleam in his mustache, which is neatly trimmed. He is a young-looking 34, but already there is a shadow of how he will age around the eyes and drawn cheeks, how the veins in the hands will rise. His voice is soft. A long bus ride away, beyond the ragged northeast rim of Cairo, his 4-year-old son waits for his father's return.

Mohamed said he will not teach the boy about gold or how to carve a locket.

"No," he said. "My son must have a college degree. What I didn't do he will do."

Many fathers say such things these days. Others have collected the bodies of their sons from morgues, driving them to graveyards and cursing the guns of the police. As Mohamed spoke, fading streamers left over from the holy month of Ramadan crisscrossed the alley, like silver tails of birds.

There was ice to be delivered; the mallet wet, the pick ready. Tap, tap, tap. The air was hot and a man dusted with flour teetered past, balancing loaves of bread on his head. Merchants peeked from shop fronts at the scrape of footsteps, and anyone who resembled a tourist was greeted with a practiced smile and a quick "Welcome to Egypt."

Mohamed finished his rounds at dusk and left for home. He was troubled. His ice chest had no lock; people were sneaking in and stealing from him. His boss appeared unconcerned. Mohamed complained the next day, and the next. He argued with the boss, who refused to spend money for a lock. The men yelled at each other. A few days ago, Mohamed quit and stormed out of the bazaar.

He had gone from gold to ice to nothing.

Special correspondent Ingy Hassieb contributed to this report.

Follow Jeffrey Fleishman (@JeffreyLAT) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Dodgers pitchers are quite the hit at the plate

Every time Greinke pitches, if he doesn't get any hits ... I tell him he had a bad game."

A virtual way to be with their deported friend

The more we learn about immigration, the more unfair it seems."

An adopted son discovers more than he expected

I had misjudged the magnitude of this meeting — both for my biological mother and for me."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.