My grandfather kept ledgers logging every day he worked in the U.S. The dry entries ‚ÄĒ ‚Äú18 boxes of cherries, $4 per box‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ tell a story of success against the odds.

HUAJUAPAN DE LE√ďN, Mexico ‚ÄĒ My grandmother told me about the missing notebook.

It had a blue cover, she said, and was unmarked except for ‚Äúcuaderno de trabajo‚ÄĚ written in the italicized superscript taught in elementary schools around Mexico. Kept by my grandfather when he labored on farms and orchards in the United States, the notebook recorded where he had worked, how much money he earned and ‚ÄĒ most important ‚ÄĒ where that money went.

The problem, my grandmother said, was that the ‚Äúnotebook of work‚ÄĚ probably had been destroyed or thrown out. My grandfather, a man of few words, didn‚Äôt know where it was either.

But what if that notebook wasn’t gone?

After graduating from college in 2023, I traveled to the Mexican state of Oaxaca to visit relatives and to report on the effects of remittances sent back to Mexico. I was unable to find old bank records or receipts, but my grandmother mentioned the missing notebook one night after dinner.

I knew I had to see it to learn more about my family’s history, so I went to the last place Herminia Rodríguez Andrade remembered having seen it: the village where she and my grandfather, Pedro Martínez, were born in the 1940s and started a family.

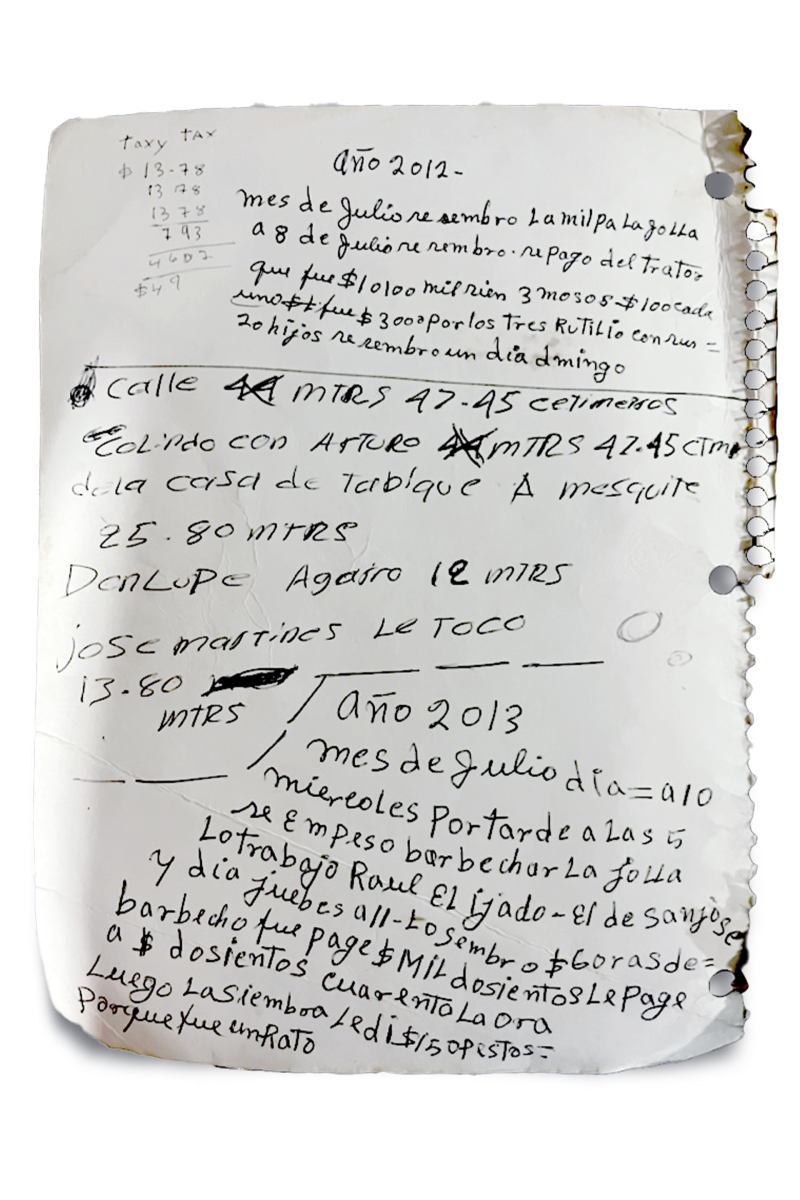

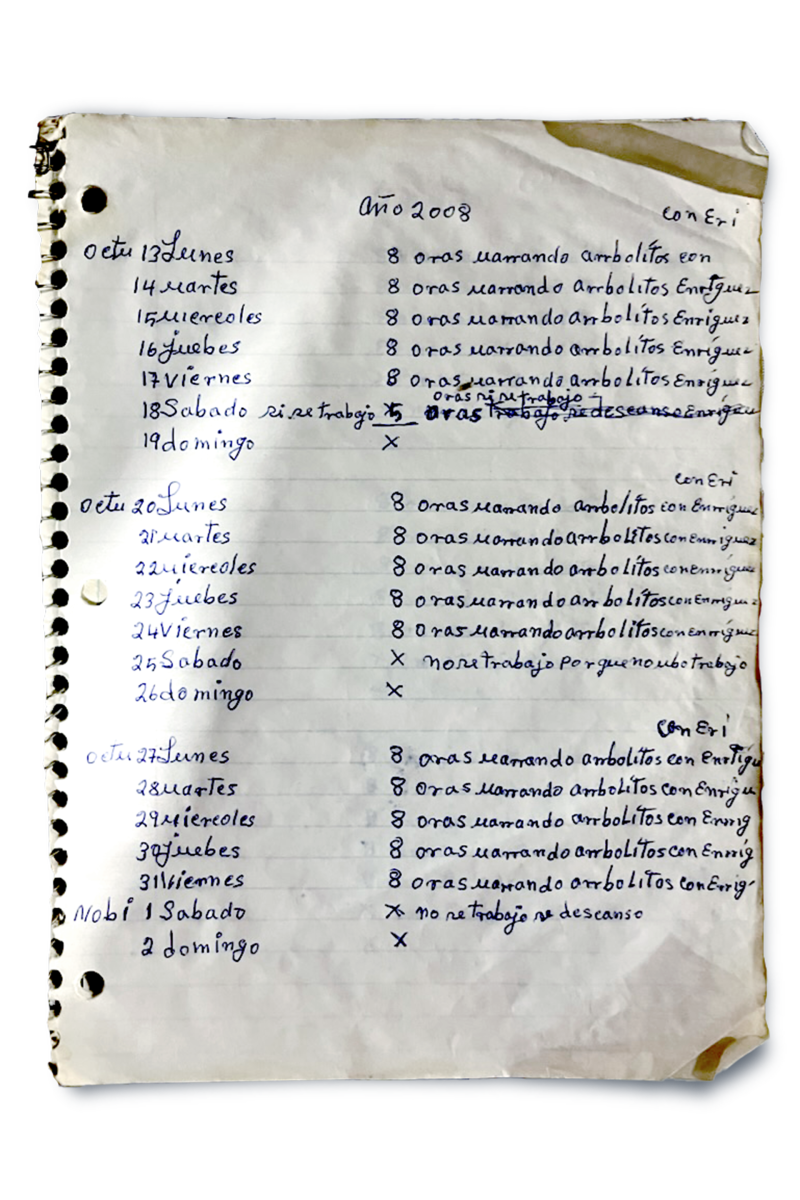

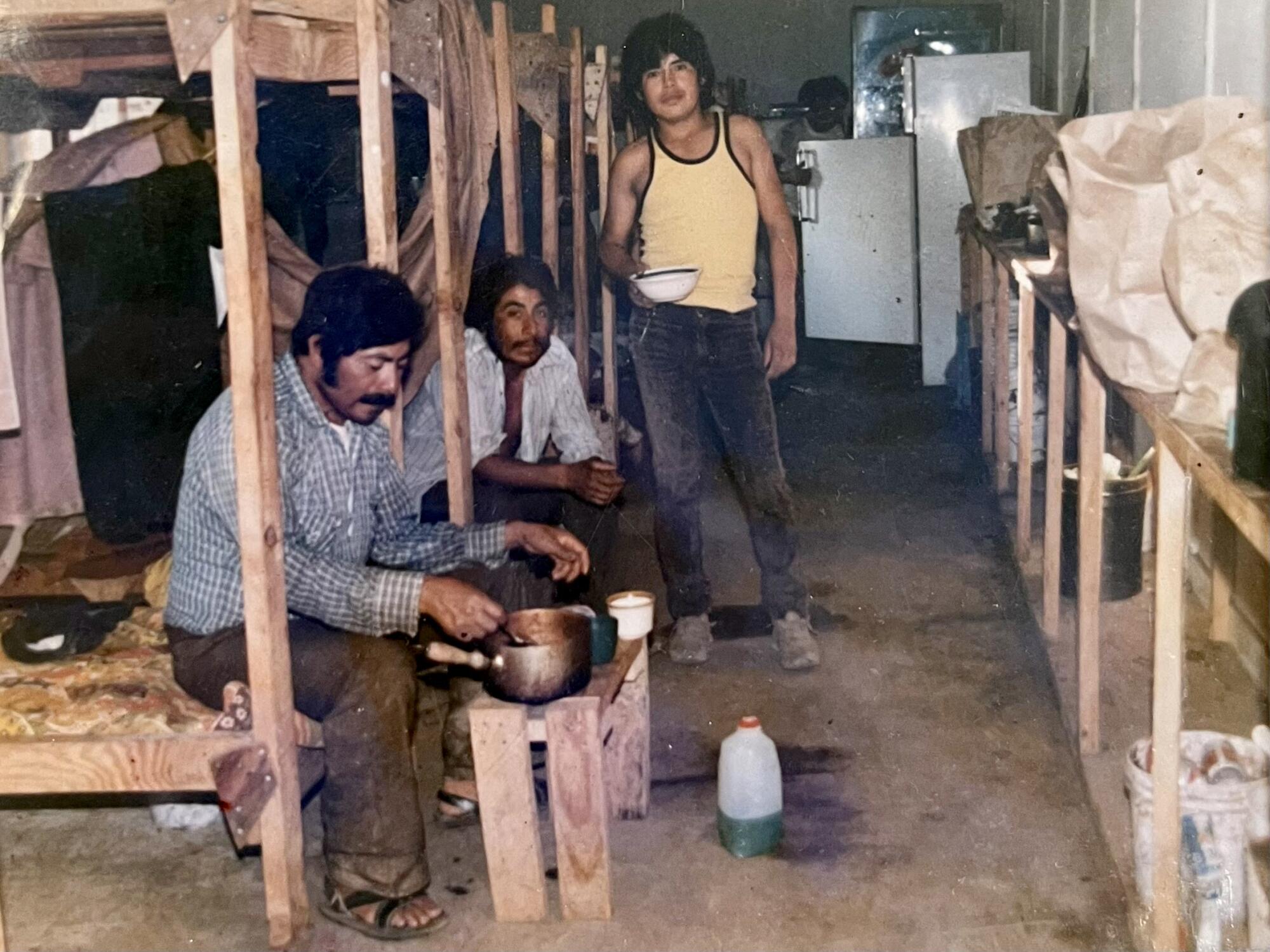

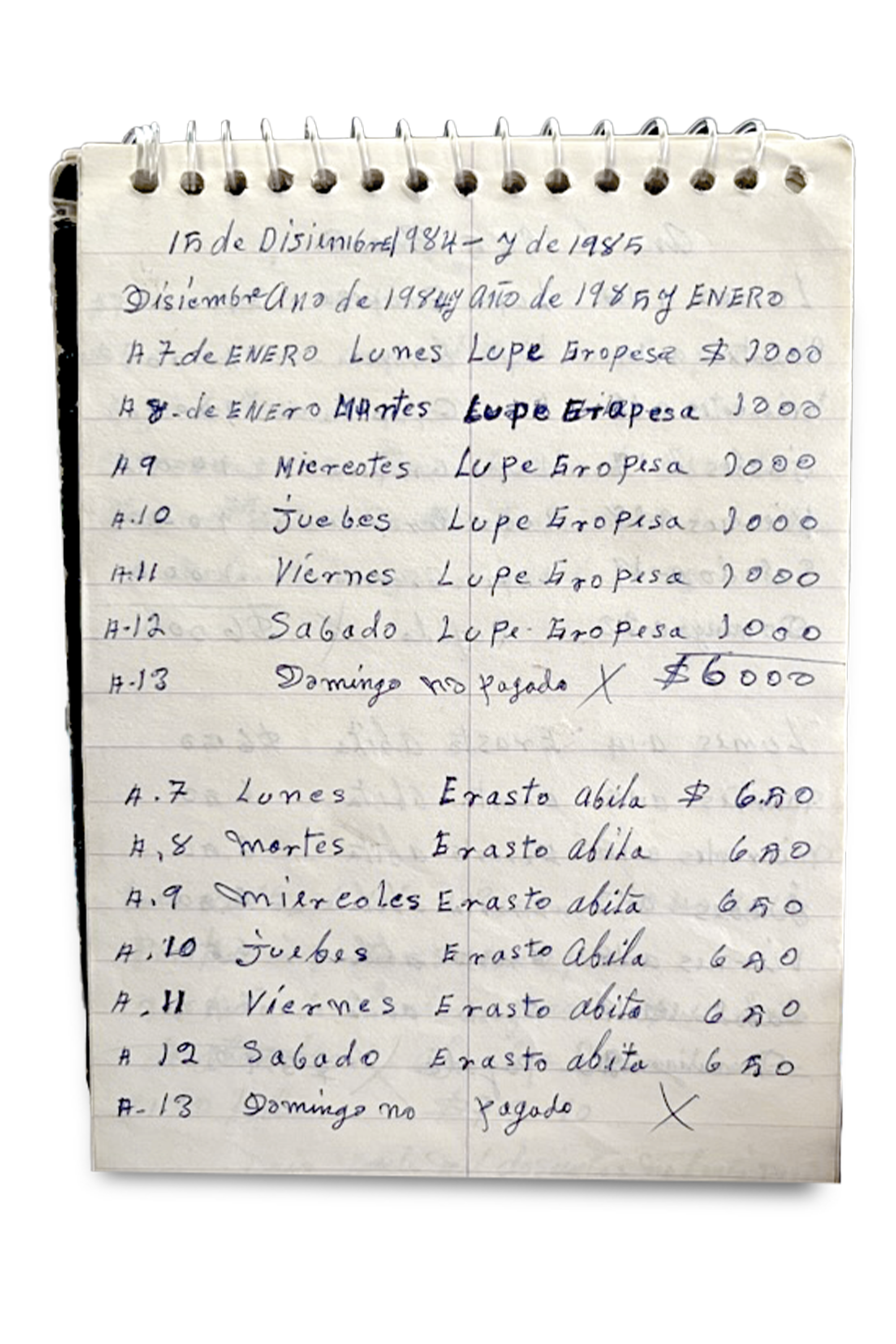

Inside the two-room adobe house where the couple and their eight children once lived as subsistence farmers, I sifted through photographs and utility receipts filling a cardboard box that sat next to the only bed. At the bottom, I found it: a Mead brand spiral-bound notebook. The front cover nearly fell off when I opened it, revealing page after page of entries that were dry, even monotonous.

‚ÄúOctober 3, Friday. Eight hours laying wire with Enriquez.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúNovember 21. Friday. Eight hours pruning pears. Pruning started today.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúDecember 5, Friday. Eight hours pruning apples with Eri.‚ÄĚ

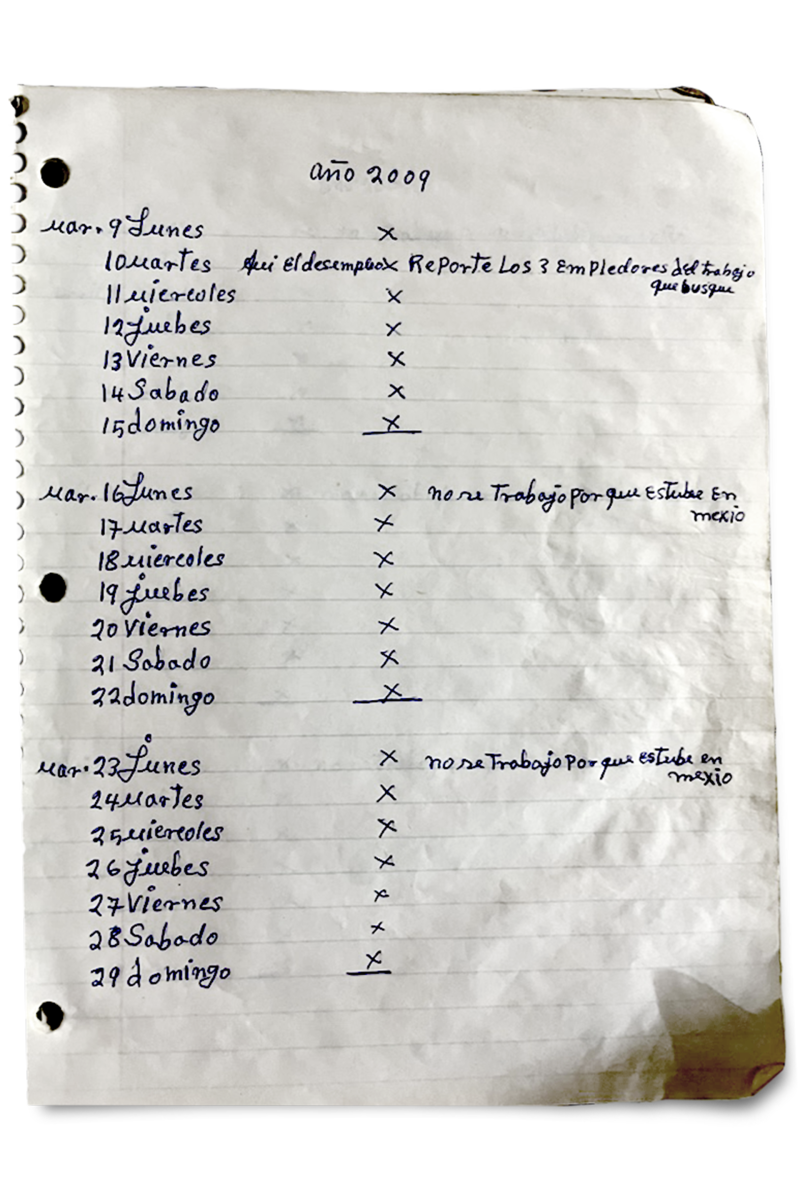

Page after page, line by line, I saw how Pedro lived and worked in 2008 and 2009 in the orchards of central Washington. They traced every job he had and even indicated the days rain cut a workday short.

The notebook was the first of about a dozen ledgers that I would find in the adobe house and at the family’s current home in Huajuapan de León, a Oaxacan city of 80,000.

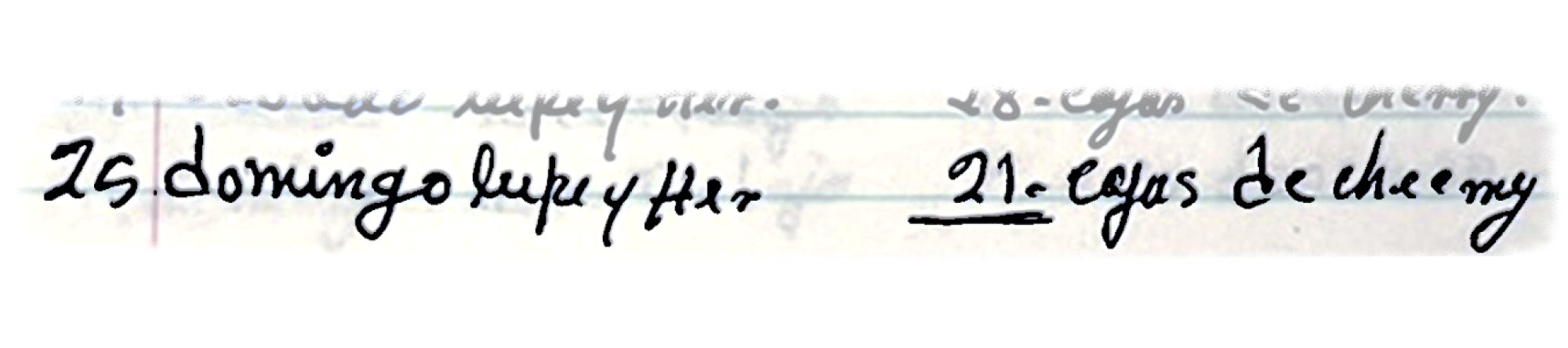

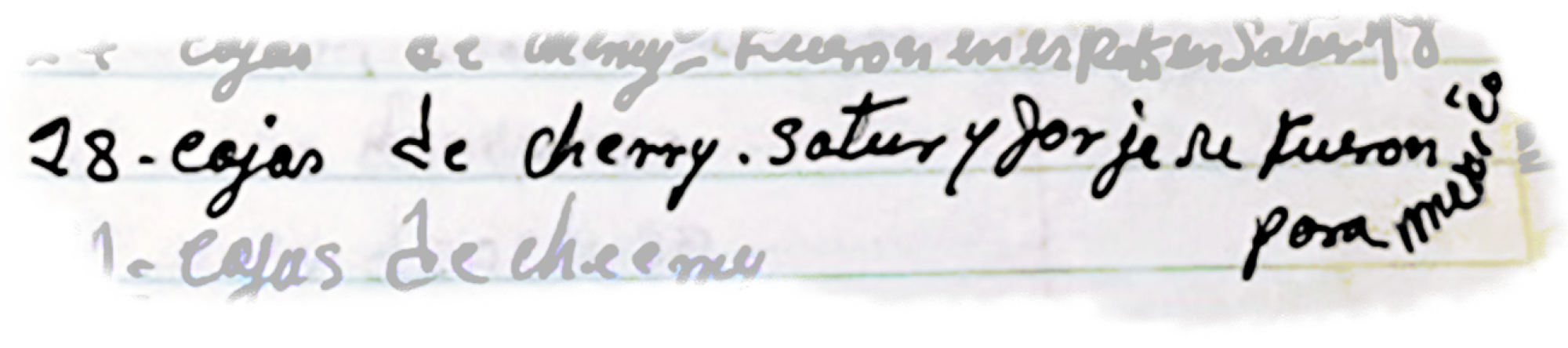

Pedro often recorded what he earned, as in this entry from 1999: ‚ÄúJuly 22, Thursday. 18 boxes of cherries. $4 per box.‚ÄĚ

He also recorded the day he made nothing at all. Using an X to indicate zero, on July 26, 1990, Pedro wrote, ‚ÄúX because there was no work.‚ÄĚ Some weeks had lots of Xs. The last entry from that year, in November, reads, ‚ÄúOn Thursday I left for Mexico at 5 a.m.‚ÄĚ

With entries from California, Oregon and Washington state, the books were kept to document the transfer of money. Now, in a larger sense, they tell the story of how remittances sustain life in Mexico. Over time, remittances provided a source of modest generational wealth for my Mexican grandparents, aunts, cousins, nieces and nephews ‚ÄĒ to the point where my American family no longer feels the need to send money, except in times of emergency.

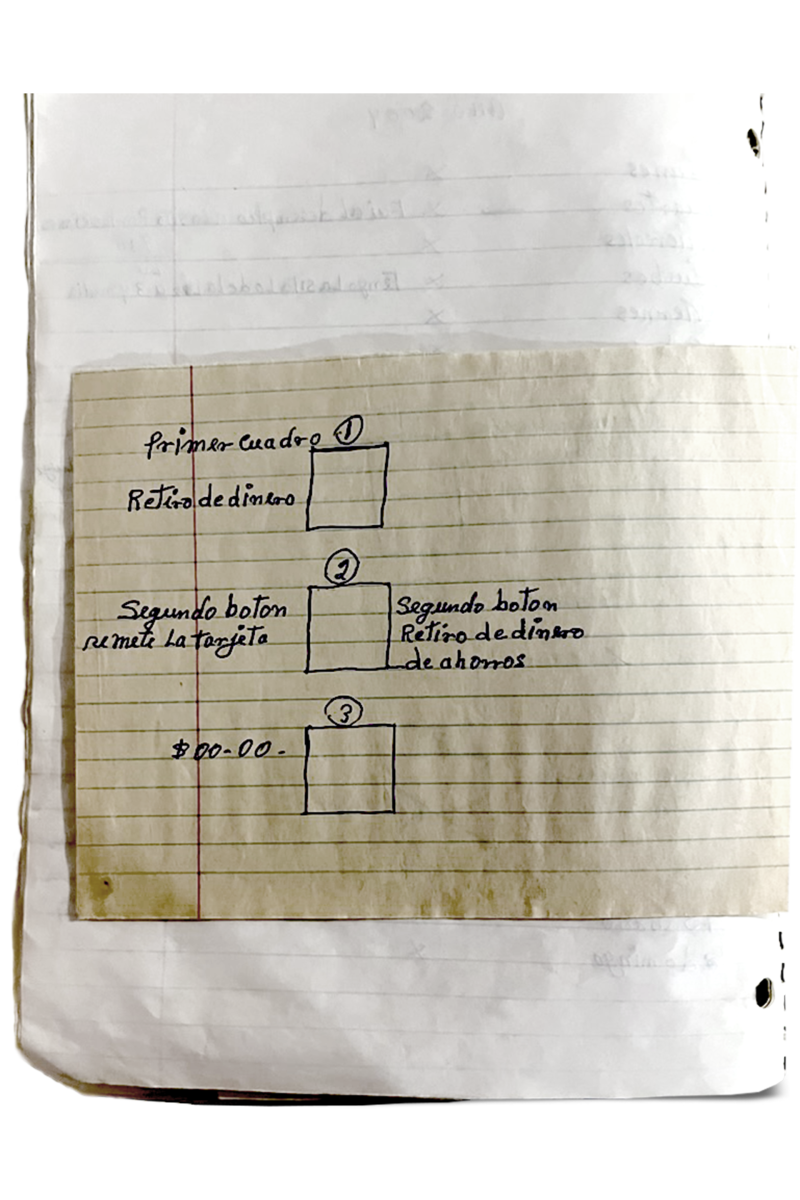

The notebooks capture pieces of Pedro’s life, work and aspirations from 1981 to 2010, when he returned to Mexico for good. They are far richer than any bank records.

Sometimes, Pedro drew sketches of the house he planned to build in Huajuapan someday. It would have six rooms across two floors, with windows along the north side.

Other times, he wrote English phrases that he copied from paperwork or learned from classes in the United States: ‚ÄúYour employee number with Wyckoff Farms is 46450. Please put it on the card.‚ÄĚ He also wrote down ‚Äúcherry,‚ÄĚ as in ‚Äú18 cajas de cherry,‚ÄĚ instead of the Spanish ‚Äúcereza.‚ÄĚ

Pedro’s notations, though repetitious and even tedious, opened my eyes to his meticulous nature, the way he viewed each dollar as one that couldn’t fall through the cracks.

Money sent from the United States plays an oversized role in the economy of rural Mexican states. In Oaxaca, home to more than 4 million people, residents collectively received $2.9 billion in remittances in 2022 ‚ÄĒ equal to about 12% of the state‚Äôs gross domestic product, according to the Bank of Mexico and government figures.

For many recipients of remittances, the funds are used to fill gaps in social services and to supplement a minimum daily wage of 207 pesos, or roughly $10.

More than 80% use the transfers for basic needs such as food and clothing, according to the bank BBVA, while fewer than 15% use the money for education. Even fewer use it to buy land, another way in which my family is an exception.

Since the money is often not invested in something that could ultimately generate income or promote development, like starting a business, its long-term impact is limited, said Jose Ivan Rodríguez-Sánchez, a research scholar at Rice University’s Baker Institute Center for the United States and Mexico.

Generally, he said, people stay poor.

But in my family, remittances have been used for decades as a pathway to upward mobility.

And it all began, as with the notebooks, with envelopes always bearing three stamps.

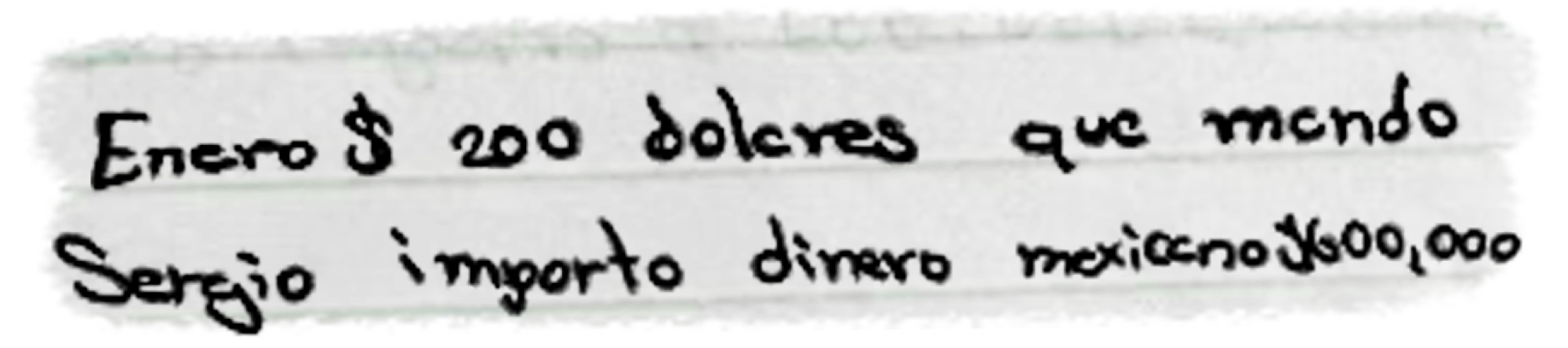

March 12, 1992: Sergio Martinez sent $200, worth 600,000 pesos

Growing up in Wenatchee, a small city in Washington state known as ‚Äúthe Apple Capital of the World,‚ÄĚ I knew the importance of remittances from weekly trips to the tienda mexicana. There, my dad, Sergio, would buy telephone cards and call his parents, Pedro and Herminia, to check on the family or confirm they received the money he‚Äôd sent.

I knew that my grandparents grew up the way most rural Mexicans did in the 20th century: extremely poor. I knew that poverty led Pedro to follow a gushing stream of laborers from Mexico to chase farmwork in the western U.S. Pedro drifted from San Diego County to Oregon’s Willamette Valley, until he found a job he liked picking fruit in arid central Washington.

But there’s a difference between stories passed down and truths I could learn as a journalist. It was only while reporting in Huajuapan that I understood the coordination it took to save my relatives from food insecurity and the discipline it took to avoid using newfound wealth for unnecessary purchases.

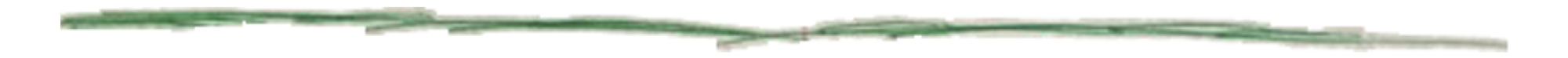

When Pedro first crossed the border without documentation in 1978 to pick strawberries in Escondido, he lived in a tent on a patch of flat dirt near the farm where he was working. Intent on saving almost every dollar of his pay for his return to Oaxaca, he ate wild cactus he harvested from the hills, recalling that they were ‚Äúdifferent ‚ÄĒ no, worse ‚ÄĒ than the cactus at home.‚ÄĚ

On his first trip home, Pedro brought an envelope thick with cash. It was the largest sum of money the family had ever deposited in a bank at one time: $3,600.

As detailed in the notebooks, that sum was the result of months of modest accumulation: $100 on a good day, when his wages were above $4 per box of fruit picked and he could fill more than a dozen boxes; less than $50 on others, when the dry summer heat made it unsafe to continue work in the afternoon.

After returning to the United States, he began to send home cash in monthly envelopes ‚ÄĒ always using three stamps to ensure prompt delivery. Herminia and her young children would pick up the mail and hold these envelopes up to the sun, estimating their value by the silhouette of the bills inside.

In 1985, the couple purchased land in Huajuapan, down the street from the central produce market. They built a small house where seven of their children grew up. Each time Pedro returned, he would build a wall to expand it.

When my father and two of his brothers, Jorge and Saturnino, joined Pedro in Washington in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with remittances paying the coyotes who got them across the border, they shared a room in a house and didn’t get to keep most of the money they earned picking cherries at $4 per seven-gallon crate. They let Pedro allocate part of their paychecks for their living essentials.

The remainder was sent to Huajuapan, where their sisters logged each remittance payment in yet another notebook for Pedro to review each time he returned for visits.

The girls bought new shoes and ate more meat, but along with Pedro’s financial savvy came a stinginess that extended to his family. He refused to pay for any education not provided by the government.

My grandfather never saw the point of using remittances for educational purposes ‚ÄĒ or for any expense beyond what he deemed immediately essential. This view is common among many Mexican recipients of remittances, either because their finances are so limited that extra money is spent on necessities or because they undervalue education as a key to advancement, according to Tania Castillo Villegas, who studies the effects of remittances at University of the Isthmus in southern Oaxaca.

By the mid-1990s, my father was in his early 20s and starting to become disillusioned with life in the U.S. He had left Huajuapan to avoid becoming a laborer like his father, and yet the only jobs he could find were in Wenatchee’s orchards.

Soon, he stopped taking agricultural jobs, enrolled in English classes at a community college and began to work in restaurants. Using the same method of accounting pioneered by their father in the blue notebooks, he and his brothers directed their remittances to go toward their sisters’ education.

My dad paid for his sister Nubia’s accounting school. Daifa Norma went to a teachers’ college in Mexico City, and Maribel went to Oaxaca City for nursing school.

July 25, 1999. Lupe and Herminia picked 21 boxes of cherries.

Eventually, Pedro, now 80, settled permanently in Huajuapan, his spine bent by years of climbing ladders with 40-pound bags of apples on his back. Macular degeneration slowly took over his vision until he was blind. And in July 2023, after coughing up blood for several days, he stopped eating altogether.

His gallbladder might burst at any time, a doctor warned, and the family had to decide whether Pedro was strong enough for surgery. Although an operation was risky, and the doctor gave a 20% probability of a full recovery, the chances of survival appeared lower without an operation.

The family opted for surgery at a private hospital in Huajuapan rather than at the nearest public hospital in Oaxaca City, which would have required a bumpy three-hour ambulance ride.

Sergio, my father, arrived a day after the surgery, using the frequent flier points he had stockpiled for years to secure a last-minute flight from Seattle to Mexico City. When he arrived in Huajuapan, he was still unsure of his father’s fate. At the hospital, he walked into Pedro’s room and found him awake and responsive. The toxic gallbladder floated in a dark liquid inside a plastic jar on the bedside table.

The decision to take Pedro to a private hospital rather than a subsidized public institution, despite the uncertainty of what the final bill would total, exemplifies the family’s financial stability. The hospital bill exceeded 100,000 pesos (roughly $6,000), an astronomical price for many in the region but a cost that the family could afford with contributions from Pedro’s children.

Remittances did not pay for Pedro’s potentially lifesaving surgery, at least not directly. But they did facilitate the generation of wealth that allowed my father and his siblings to save money for unexpected medical expenses. My aunt Maribel, the family nurse who tended to Pedro’s wounds after his surgery, gained the skills she had from the investment of remittances.

It has been years since the family has been concerned about having enough to eat. Though the family once relied on a field they planted with crops, that field has essentially been allowed to go wild, with corn and cactus growing on their own, along with avocado and mango trees. Herminia and Pedro now harvest whatever the field yields ‚ÄĒ something to supplement the pounds of meat and masa that are purchased each week to feed the home‚Äôs eight permanent residents: an assortment of children and grandchildren, and a handful of regular visitors.

The family has, in a way, grown out of its dependence on remittances.

My father, who got his green card in 2000, no longer pools money or sends set amounts each month. The investments he and his brothers made in education have paid dividends for those still living in Mexico. Norma is a teacher in Mexico City, Maribel a nurse in Huajuapan. The third generation, my cousins, are able to take private English classes and participate in enrichment programs that my father and his siblings could only have dreamed of.

Other Mexican families have not been as fortunate as mine. Sometimes, accidents or injuries prevent migrant workers from making enough to send money that can accumulate as wealth. In some households, remittance money is ‚Äúspent on something without any benefit for the family,‚ÄĚ said Castillo Villegas.

July 23, 1991: Pedro and Herminia picked 28 boxes of cherries. Saturnino and Jorge left for Mexico.

Shortly after my grandfather’s surgery, on a rainy evening in Huajuapan, my cousin Carmen Méndez Martínez sprinted across the concrete driveway to where the family was seated at a table.

‚Äú¬°Me aceptaron en la UNAM!‚ÄĚ she said, panting. She had been accepted to attend the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the country‚Äôs most prestigious public university.

The adults congratulated her, but their tone was somber. It meant that Carmen would be leaving Huajuapan and, if her aspirations of exploring the world as a doctor were fulfilled, she would not be returning. For Nubia, her mother, it brought to light concerns of the family’s closeness. Would her daughter visit? Would she still feel a duty to help her family?

Carmen is one of 16 grandchildren under the age of 21; the return on my family‚Äôs educational investment is just beginning. One cousin wants to be a dentist, another wants to join the U.S. military. Inevitably, they will continue to spread out. And to think those ambitions can be traced back to ledger entries such as ‚ÄúDecember 5, Friday. Eight hours pruning apples with Eri.‚ÄĚ

Three weeks after Carmen was accepted to UNAM, she was on her way to Mexico City. She said her goodbyes to her stoic aunts and siblings, tears in their eyes. When she got to Herminia, her grandmother, Carmen bowed her head for a blessing.

Xavier Martinez is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.