CHIMAYO, N.M. â Enrique Garcia staggered to his feet, took a few shaky steps forward, then fell back into his wheelchair. He stood and did it again. And again.

His wife, Lupe, maneuvered the chair in front of him so he could brace himself while slowly pushing it up the crowded road toward their destination.

They still had about a quarter of a mile to go.

The couple are among the roughly 300,000 people who each year make the pilgrimage to the Roman Catholic shrine known as the Santuario de Chimayo looking for a miracle, spiritual renewal or forgiveness.

âI have deterioration in both knees and ankles,â Garcia, 77, said last week. âI will put the holy dirt on them. It doesnât take away the pain, it helps me live with the pain.â

The shrine has become the most significant Catholic pilgrimage site in the country. People come all year, in all ways. Some walk 90 miles from Albuquerque or 27 miles from Santa Fe, camping along the roads or behind churches. Most drive part way and walk the rest.

Pain is part of the pilgrimage.

âWe come for the sacrifice,â said Lupe Garcia, 74. She and her husband had driven from Albuquerque and parked as close as they could to the church.

Over the years, Chimayo has morphed from an unincorporated collection of close-knit neighborhoods into a major tourist attraction and a destination for spiritual seekers. Newcomers are moving in. Over the last three years, Chimayoâs population grew to 3,208 from 2,779.

At the same time, some of the rich, complex history of the region is fading, including the unique dialect of Spanish spoken only in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

The town of EspaĂąola, N.M., has struggled with drug addiction for generations. But fentanyl has contributed to rising homelessness and overdose rates.

But the pilgrimage endures.

âPilgrimage is praying with your feet,â said Pat Trujillo-Oviedo, a local historian whose family has lived in the area for 12 generations. âItâs an active prayer. There is a reason you are making a pilgrimage and mostly itâs to purify yourself.â

In the days leading up to Easter, up to 40,000 pilgrims come through the Santuario, a small church that forms the centerpiece of the shrine. They pray, visit various chapels and enter a small room where crutches hang from the wall alongside written testimonials of healings.

A few steps away is a tiny chamber known as âel pocito,â or little well, where the pilgrims shovel âholy dirtâ from a small hole into baggies, baby food jars and assorted vials.

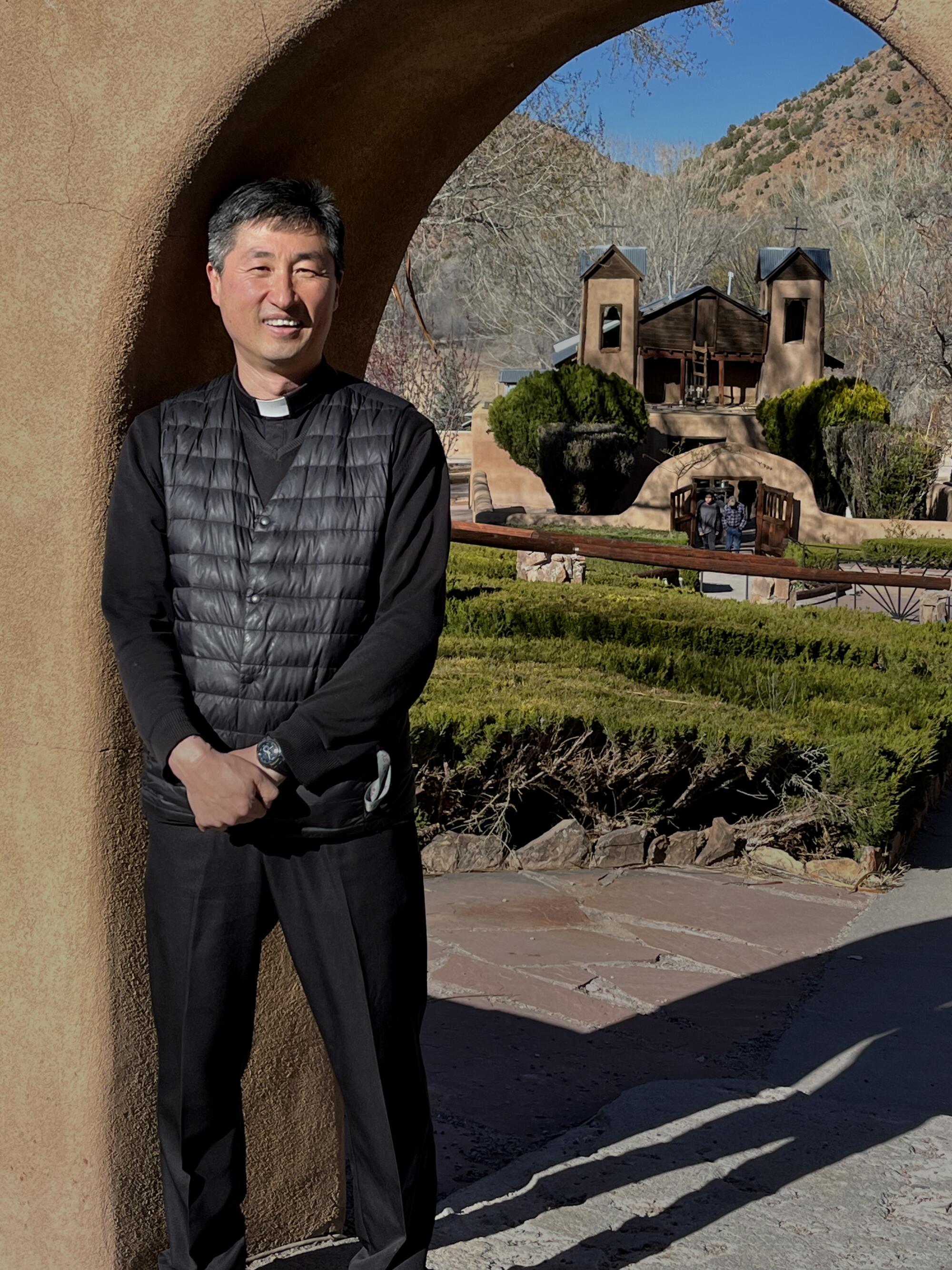

âWe refill the dirt every day,â Father Sebastian Lee, the priest at the shrine, said last week during a rare break from blessing pilgrims, topping up the holy water and making sure the dirt didnât run out.

âThere is a construction company that has been bringing in the dirt for 70 years now,â he explained. âThey bring a truckload every two or three months and we bless it.â

Tests have revealed nothing special about the soil, which mostly originates in the nearby foothills. But Lee said he believes it can work miracles through the power of faith.

People tell him the dirt has cured skin diseases, brain cancer and infertility. Heâll often ask for a medical report to send to a doctor in Santa Fe to determine whether the healing happened without medical intervention. Heâs lucky to get one a year.

âI keep telling people that if they are serious about this they have to send me a report,â Lee said. âPeople have told me that they have seen someone come in in a wheelchair and walk out. It happened twice, but I didnât see it. I would like to see it.â

The Catholic Church has taken no position on the claims.

Lee said healing comes in many forms.

âPhysical healing is very important, but to some people having hearts that are peaceful and joyful â that is real healing,â he said.

The Santuario was built by Don Bernardo Abeyta, a member of the Penitente Brothers, a Catholic lay order once known for extreme acts of penance including self-flagellation.

According to legend, in 1810 Abeyta saw a light shining on a hill. He investigated and found a crucifix sticking out of the ground where the holy dirt sits today.

He took the crucifix to a nearby church. By dawn it was gone and back on the hill. This happened three times. Convinced he was witnessing something miraculous, Abeyta built a small chapel on the spot. In 1813, a shrine was constructed and dedicated to Christ of Esquipulas, a pilgrimage site in Guatemala said to have healing clay.

The early Native American inhabitants of the area, a Puebloan people who spoke the Tewa language, also believed the dirt was medicinal.

The mystery of the crucifix and the curative dirt proved irresistible to pilgrims who slowly trickled in. The Good Friday pilgrimage, the largest of all, began after World War II. A handful of local soldiers, captured by the Japanese in the Philippines during the war, vowed to make the pilgrimage every Good Friday if they survived. They lived and kept their promise.

When Father Casamiro Roca took over the church in 1955, it was in danger of collapse. He repaired it while promoting the pilgrimage and the holy dirt. The shrineâs popularity grew. Some called it the âLourdes of Americaâ in honor of the French shrine where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared, followed by healings.

Roca began to lament the very crowds he helped foster.

Before his death in 2015, he told a journalist with the Santa Fe Reporter: âItâs the faith that heals, not the dirt!â

Last week, as Good Friday approached, the Santuario sprang to life. On Thursday, Penitente Brothers from the nearby village of Cordova knelt near the altar and recited the rosary for an hour in Spanish. The church pews were full. Wooden saints and statues of Christ looked on from every direction. People lighted candles, others ducked into an alcove to write prayer requests on bits of paper.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

David Ortiz, 58, was sitting just across the road drinking coffee with his mother, Dee Silva, 75, after visiting the church.

âWhen I was in high school our football team was really bad,â Ortiz said. âSo I prayed to God that if he let us win, I would make this pilgrimage every year. We won and I have been coming ever since.â

Ortiz, who lives in Albuquerque, usually walks for eight or nine hours until he reaches Santa Fe and the next day does another eight or nine hours to Chimayo.

âOver the years I have come for different reasons,â he said. âI pray for my mom. I ask for God to give her another 10 years.â

âOnly 10?â asked his mother, who drove to the shrine.

âAnd then 10 more and 10 more,â he quickly added. âThis year I want to ask the priest to bless my marriage and make it last 100 years.â

Chimayo is the spiritual hub of a region steeped in Catholicism dating to the arrival of Spanish missionaries in 1598. Hispanic settlers and their livestock came along with them. Lacking enough priests to serve the far-flung outposts, the Penitente Brothers helped fill the gap. They still do.

In Truchas, about eight miles north of Chimayo, a dozen or so Penitentes walked somberly up the hill and into the Morada de Nuestra SeĂąora del Rosario. The brothers meet in plain, stucco chapter houses called moradas.

Though secretive about their ceremonies, the groupâs leader, Jeremiah Martinez, opened the door to the morada, revealing a simple altar with crucifixes and a few wooden pews.

Martinez, 66, has been a brother since he was 12.

Over the years, the number of brothers has dwindled, he said. They sing to those in nursing homes, pray for the dead, chop wood, hold services and do chores for people who canât.

âWe are highly misunderstood because of stories of people wearing crowns of thorns and flogging themselves,â Martinez said. âWe donât do that. We realized that God didnât want sacrifice. He wanted obedience.â

Pope Francis begins new decade as âa bit of a Californian.â That means lots of love â and hate

Pope Francis, whose leadership of the Roman Catholic Church has resonated with many Californians, celebrates his 10th anniversary as pope on March 13.

As morning broke on Good Friday, pilgrims began flooding the streets leading into Chimayo. New Mexico State Police blocked the main road into the shrine to vehicles.

Elderly women wearing black headscarves mixed with excited children, families and leather-clad bikers all making their way toward the shrine. A few carried crosses bearing the photos of deceased loved ones or those in need of prayer. Vendors hawked roasted corn and peeled mangoes drizzled with red chili.

âThis line for the church, this line for the holy dirt!â shouted a volunteer in a fluorescent orange vest. The dirt line stretched to the street.

Jerry Barreras, 63, was in the dirt line. Heâs had eight back surgeries and done the pilgrimage for 25 years. Faith and holy dirt help him cope with the pain.

Father Lee appeared outside the church.

âThe father is handing out blessings â he is right by the door,â Barreras said. âGo and get blessed!â

A procession carrying nearly life-sized wooden statues of a bound and bleeding Jesus followed by the Virgin Mary moved down the road, parting a sea of believers.

At the back of the march were dancers in Native American attire beating drums and carrying banners with the words âViva La Virgen de Guadalupe.â

Andrea Vigil, 60, watched it all. When she was younger, doctors told her she was infertile.

âWe gave up on having a child, but then I rubbed some holy dirt on my belly and I had a baby,â she said.

Five strangers gathered at a hot springs in New Mexico last week. The priest prayed, dipped the faithful backwards, into the depths, then lifted them again toward the morning light.

Enrique Dominguez, 16, walked six hours from Espanola, carrying a drum.

He said he was there because of Santo NiĂąo de Atocha â the Holy Infant of Atocha â to whom one of the chapels is dedicated. A representation of the young Jesus said to have fed Spanish prisoners of the Moors in the 13th century, the saint wore tattered shoes â the reason that hundreds of tiny shoes are stapled to the roof of the chapel.

Enrique had three open heart surgeries, and early this year doctors suggested a heart transplant.

âThatâs when Santo NiĂąo told me I didnât need it,â he said. âHe came to me at night. I have been fine for the last four months.â

He stood before the shrine and beat his drum loudly.

Father Lee said that one challenge of his job is comforting pilgrims who donât get the miracles they seek.

âIf they donât get cured I tell them we are all here temporarily. Sometimes we suffer, we meet the suffering Jesus and join with him,â he said. âWhether it happens or not, your heart is a sanctuary. God lives in your heart. Be at peace. If you have to go, leave in peace.â

Gary Gonzalez, 56, understands.

He has done the pilgrimage since he was in high school in Santa Fe. When he married, he made the journey with his wife. She was later diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and they came seeking a miracle. She died just months later.

He remarried and kept coming. He plans to continue as long as possible.

âI have seen too many healings to count,â he said. âI wish my wife could have been healed, but that wasnât Godâs will.â

As darkness fell people gathered behind the church to dip their feet into the cool Santa Cruz River. Others began the long walk back to cars parked miles away.

But in the hills and along the roads, glow sticks and flashlights shone as pilgrims continued walking toward the shrine.

Kelly is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.