Torture, darkness, rotten food: Freed Nicaraguan dissidents describe their prison ordeals

MIAMI â Constant fear. Screams and the sounds of torture. Darkness in a small cell with just a hole in the floor for a toilet.

Nicaraguan dissidents recall the months â and sometimes years â they spent in the notorious prisons run by the regime of President Daniel Ortega.

âThose were three terrible years. There were threats, and I thought they might kill us at any moment,â said Victor Manuel Sosa Herrera, who was held in three separate prisons. He said water was in short supply, and what little food there was often came in the form of rotten beans.

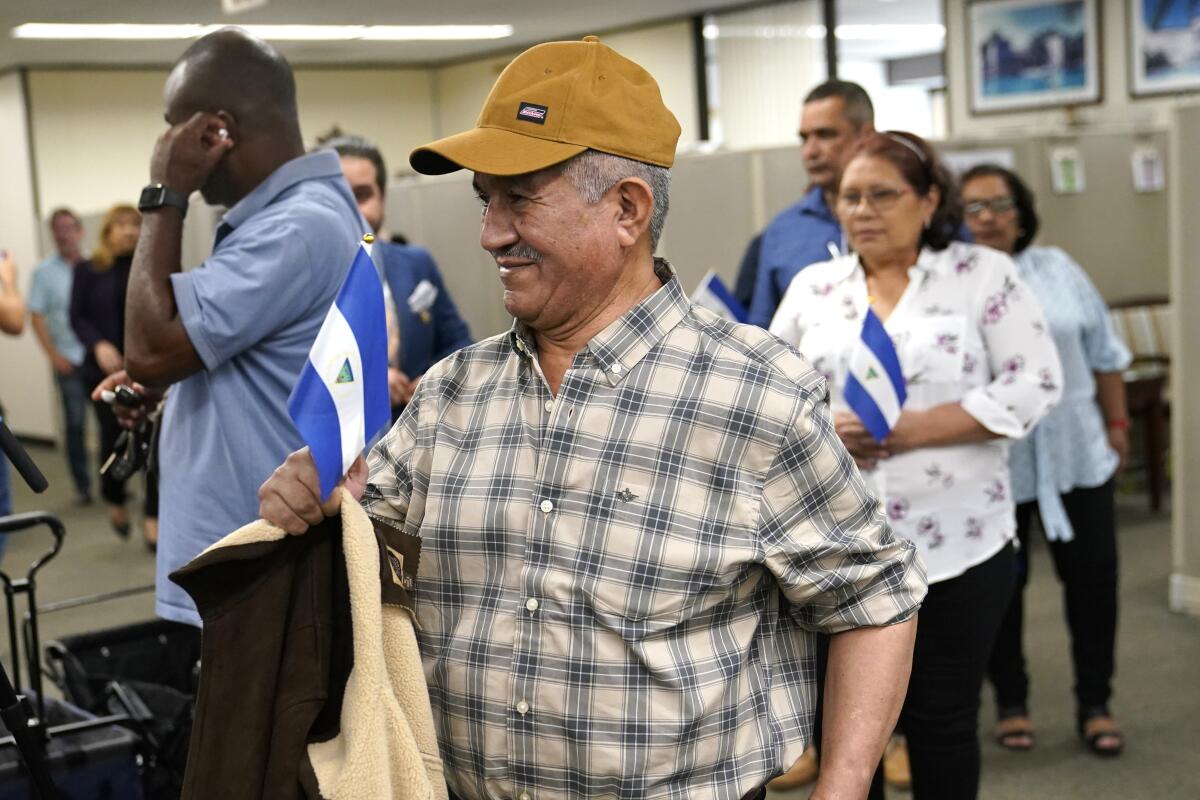

Sosa Herrera was among 222 imprisoned opposition figures released earlier this month by Ortega, as had long been sought by his critics. However, Ortegaâs government went a few steps further, deporting them to the U.S. and saying their Nicaraguan citizenship would be revoked and their property confiscated â moves criticized as banishment in violation of international norms.

The dissidents have begun telling stories of the harsh conditions in prison, where visits were strictly limited or prohibited entirely.

Sosa Herrera, 60, ran a grain and feed business in the northern Nicaragua city of Matagalpa when he was arrested in early 2020 and sentenced to 110 years in prison for treason and destabilizing the government.

Roman Catholic Bishop Rolando Ălvarez, an outspoken critic of Nicaraguaâs government, has been sentenced to 26 years in prison and stripped of his Nicaraguan citizenship.

He says he wasnât an activist in the massive 2018 protests that shook Ortegaâs government, but suspects he was arrested for his refusal to join government paramilitary squads that violently put down the protests.

At one prison, the Modelo penitentiary, he was locked up alone in a sunless cell measuring 6 by 9 feet, in the maximum security section known as El Infiernillo, or Little Hell. He says that another prisoner in a similar cell believed he had gone blind from years of living in the dark.

Sosa Herrera said he was held in isolation with only a concrete platform to sleep on. Water was turned on for an hour at a time, twice a day. The metal cell door had a steel window that opened just three times a day to pass him a âmealâ: a spoonful of rice and rotten beans. That was his only daily contact with another person.

His wife could visit him for only 15 minutes each month, and they saw each other through a glass partition.

With virtually no independent journalists left inside and foreign reporters banned from entering, Nicaragua has become âan information black hole.â

At night, he said, he could hear other prisoners being tortured.

âThe guards put them into handcuffs and shackles, and then beat them and dragged them,â Sosa Herrera recalled. âWe heard them screaming.â

The Nicaraguan government did not respond to requests for comment on the prisonersâ accounts.

Ortega has maintained that his imprisoned opponents and others were behind the 2018 street protests that he claims were a foreign plot to overthrow him. Tens of thousands of Nicaraguans have fled into exile since security forces violently put down those protests.

In Nicaragua, he was the âmarathon man,â famous for jogging through city streets to protest the government. Now heâs trying to re-create a bit of his homeland in L.A.

In some ways, those held in solitary confinement might have been lucky.

IsaĂas MartĂnez Rivas, a milk delivery worker, ran an independent online media outlet of the kind Ortegaâs government hates.

MartĂnez Rivas, 38, was arrested in late 2021 in front of his wife, their baby and the coupleâs adolescent son. He was dragged off to a maximum security prison without an explanation or a warrant. Six months later, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison for supposed antigovernment activity.

MartĂnez Rivas was held at the prison in Chontales, 100 miles east of Managua and two hours by car from his home.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

He was tossed into a cell with 13 other inmates, all but one of whom were common criminals.

âIt was terror â we lived in fear,â he said. The other inmates threatened the opposition prisoners and stole their food, clothing and shoes.

âIn prison I was subjected to psychological torture,â he said. âThey never let me see my family.â

He has been able to see his youngest, now 2, only on video calls from Miami.

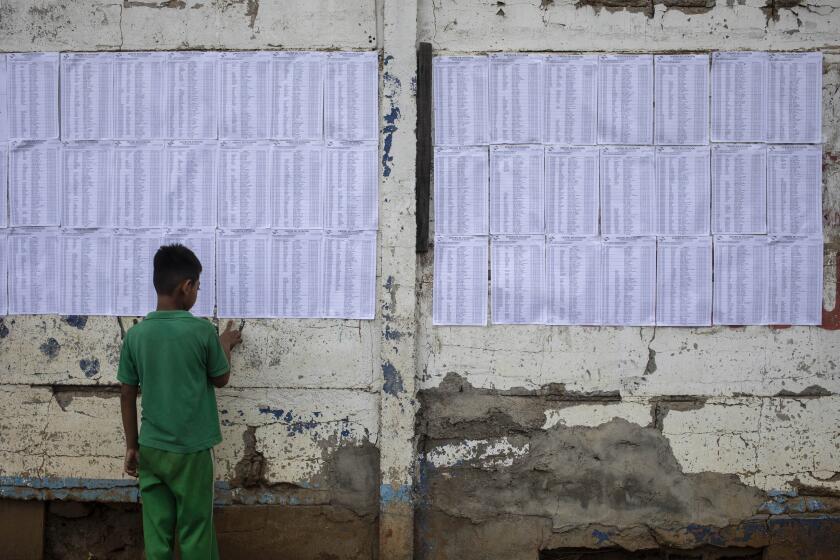

Nicaraguaâs Sandinista National Liberation Front won local elections decried as unfair in all 153 of the countryâs municipalities, cementing its rule.

Another prisoner, who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals against her family, said she still doesnât know why riot police burst into her home in November 2021 and pulled her away from her family as they were about to sit down to dinner.

A perfume distributor, the 43-year-old woman said she wasnât a political activist. But she was sentenced to 10 years in prison after prosecutors accused her of plotting to burn ballot boxes and receiving funds from abroad.

She spent 15 months locked in a cell with nine other female inmates, all of whom were in for homicide or drug trafficking. The guards would subject the imprisoned dissidents to psychological abuse, she said.

âThey would try to get at us by telling us we were going to rot in prison, to be eaten by worms,â she said.

Nicaragua has canceled the citizenship of 94 political opponents, including writers Sergio RamĂrez and Gioconda Belli, whom it has labeled âtraitors.â

Indeed, some prisoners didnât make it out.

Hugo Torres, a former Sandinista guerrilla leader who once led a raid that helped free then-rebel Ortega from prison in the 1970s but who later broke with him, died while awaiting trial. He was 73.

Torres was among opposition figures arrested in 2021 as Ortega looked to clear the field ahead of presidential elections in November of that year. Security forces arrested seven potential presidential contenders, and Ortega coasted to a fourth consecutive term in elections that the U.S. and other countries termed a farce.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.