Palestinian who was imprisoned at 13 seeks early release in case that shook Jerusalem

JERUSALEM — It was a crime that convulsed Jerusalem.

On a fall day seven years ago, 13-year-old Palestinian Ahmed Manasra and his 15-year-old cousin tore through the streets of a Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem, armed with knives. His

cousin, Hassan, critically wounded a 13-year-old Israeli boy who was leaving a candy store and stabbed an Israeli man. He was shot dead by police. Ahmed was run over by a car, beaten and jeered by Israeli passersby.

Now, Manasra, a 20-year-old in isolation and tormented by psychosis, has asked for an early release from prison after completing two-thirds of his sentence. Several courts have rejected his request, arguing that even if prisoners would ordinarily be eligible for release after so long in prison, Manasra — a “terror” convict — was not, regardless of his age or mental condition.

The Israeli Supreme Court will decide whether to hear his appeal in the coming days.

His case has been a lightning rod for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, incensing Israeli Jews who viewed Manasra as a terrorist seeking to kill Jews his own age and enraging Palestinians who saw him as the victim of a vicious mob and unfair trial, punished for a crime his dead cousin committed. A graphic video of Manasra lying in the street, bleeding from the head while Israelis taunted him, garnered millions of views.

His lawyer argued at the time that Manasra had sought to frighten Jews in retribution for Israeli policies toward the Gaza Strip, not kill them.

In the last six years since Manasra was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 9½ years in prison, doctors say he developed schizophrenia in solitary confinement and tried to harm himself and others. As of Thursday, he has spent 354 days in isolation. On Tuesday, he told his lawyer he drank bleach. Just hours later, Israel’s attorney general asked the Supreme Court to dismiss the appeal for Manasra’s early release, citing a 2018 counter-terrorism amendment.

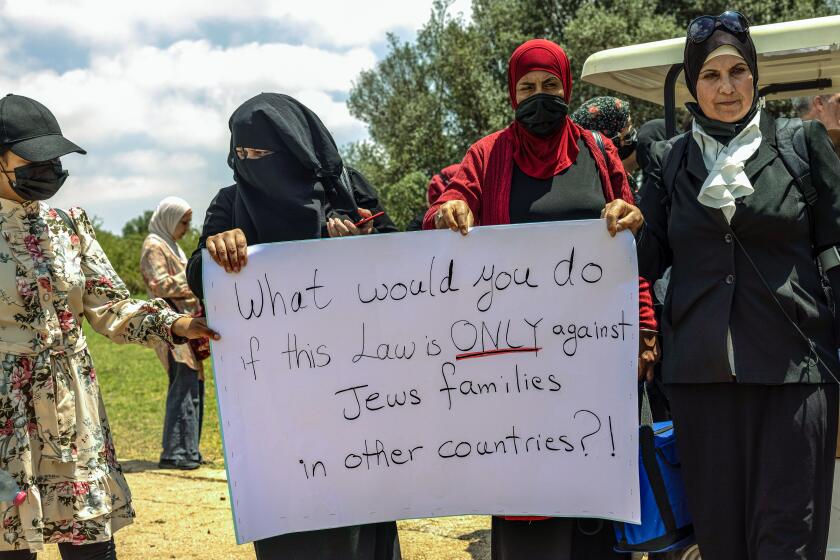

Manasra’s lawyers say it’s the first time a parole committee retroactively applied the law that forbids early release for security cases. Rights groups have decried the law as creating two separate legal norms for Israeli and Palestinian convicts.

“People who commit rape are eligible for early release, but Ahmed, who was arrested at age 13 and with a prison sentence that’s endangering his life, is not,” said Budour Hassan, an Amnesty International researcher.

Typically in Israel, those younger than 16 are sent to juvenile detention centers, where they get education and counseling in better conditions than normal prisons. Then judicial officials decide whether to transfer them. Manasra was sent to a public prison after two years.

The law prohibits extending citizenship or even residency to Palestinian spouses of Israeli citizens if they come from the occupied West Bank or Gaza.

For Manasra’s family and supporters, his transformation from a child who cared for birds and loved soccer into a mentally ill high-security prisoner with a growing tendency toward despair is a dark warning about the violence of the Mideast conflict and its effect on the younger generation.

“When he was 13 and he needed his mom the most, he was thrown in prison,” his mother, Maysoon Manasra, said from their home in Beit Hanina, in East Jerusalem. It’s just across the highway from the settlement Pisgat Zeev, where surveillance video had showed the knife-wielding boys chasing a man through the street. “The prison only offered pain.”

A rights group, Defense for Children International-Palestine, estimates that 700 Palestinians under age 18 are arrested every year in the occupied West Bank, and hundreds more in East Jerusalem. Between 2016 and 2021, the group documented 155 cases of prolonged solitary confinement in the West Bank, which Israel captured in the 1967 Middle East War.

The teenagers are typically held in a 3-foot-by-5-foot cell flooded with endless light, the group said. Their only human contact is with interrogators. They return to their families deeply scarred, said Ayed Abu Eqtaish, the group’s accountability program director.

An Israeli government deputy minister has come under fire for saying that if he could push a button to make all Palestinians disappear, he would.

“We learn from their parents that they become a different person,” he said.

According to Manasra’s family and lawyers, he is locked in a small cell for 23 hours a day. He struggles with paranoia and delusions that keep him from sleeping. Authorities first moved him to isolation in November 2021, after a scuffle with another inmate. He becomes so terrified by his hallucinations that he is taken to the psychiatric wing of Ramla Prison in central Israel every few months. Doctors give him injections to stabilize him before sending him back to solitary, his family says.

The Israeli Prison Service said Manasra “is kept in a supervision cell, and not solitary,” because of “his mental state.” It did not respond to questions about the difference between solitary and a supervision cell.

“His health condition stabilized and [there is] no reason for continued hospitalization,” it said.

An Israeli military body has released a list of rules and restriction for foreigners wanting to enter Palestinian areas of the West Bank.

His father, Saleh Manasra, described the conditions as agonizing.

“He speaks to no one but the worms on the cell floor,” he said. “He imagines someone is going to kill him. He imagines someone is chasing him.”

Saleh Manasra said prison authorities often deny his requests to visit his son. Through the plexiglass every few months, he can tell that his son “is getting worse and worse,” he said. His son’s only plea is that he be allowed to rejoin the other inmates.

Manasra’s mental anguish started soon after his arrest. Video leaked from his interrogation at age 13 shows him crying and pounding his head in frustration as Israeli interrogators shout questions at him about the attack.

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

At the time of his arrest, children under 14 could not be held criminally responsible under Israeli law. The trial dragged out. Manasra was convicted after his 14th birthday. Two years later, lawmakers cited his case as they passed a law allowing 12-year-olds to be imprisoned on terrorism charges.

“They’re treated like adult security prisoners,” said Naji Abbas, case manager at the nonprofit Physicians for Human Rights Israel.

After repeated requests, Israeli prison authorities allowed a doctor from the nonprofit organization to diagnose Manasra, then 18. Considering that he and his family have no previous psychiatric history, Jerusalem-based psychiatrist Noa Bar Haim attributed Manasra’s schizophrenia to the psychological toll of prison.

“His continued incarceration will inevitably cause his illness to deteriorate and create a permanent disability,” she warned, recommending immediate release and intensive psychiatric care.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Instead, he was placed in isolation. Over the last two years, his lawyer, Khaled Zabarqa, said that Manasra has tried to saw his wrists with whatever sharp edge he could find in his cell.

Despite the attention his case has drawn and the outrage it has spawned, his parents insist that, while growing up, their son didn’t understand the conflict that determined his life.

“They call him a terrorist. I don’t think he even knew what he was doing or what that would mean,” Maysoon Manasra said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.