SHEVCHENKOVE, Ukraine â Before war came to his village, 12-year-old Tymophiy Z. had many of the usual tween preoccupations. And his closest confidant was his diary.

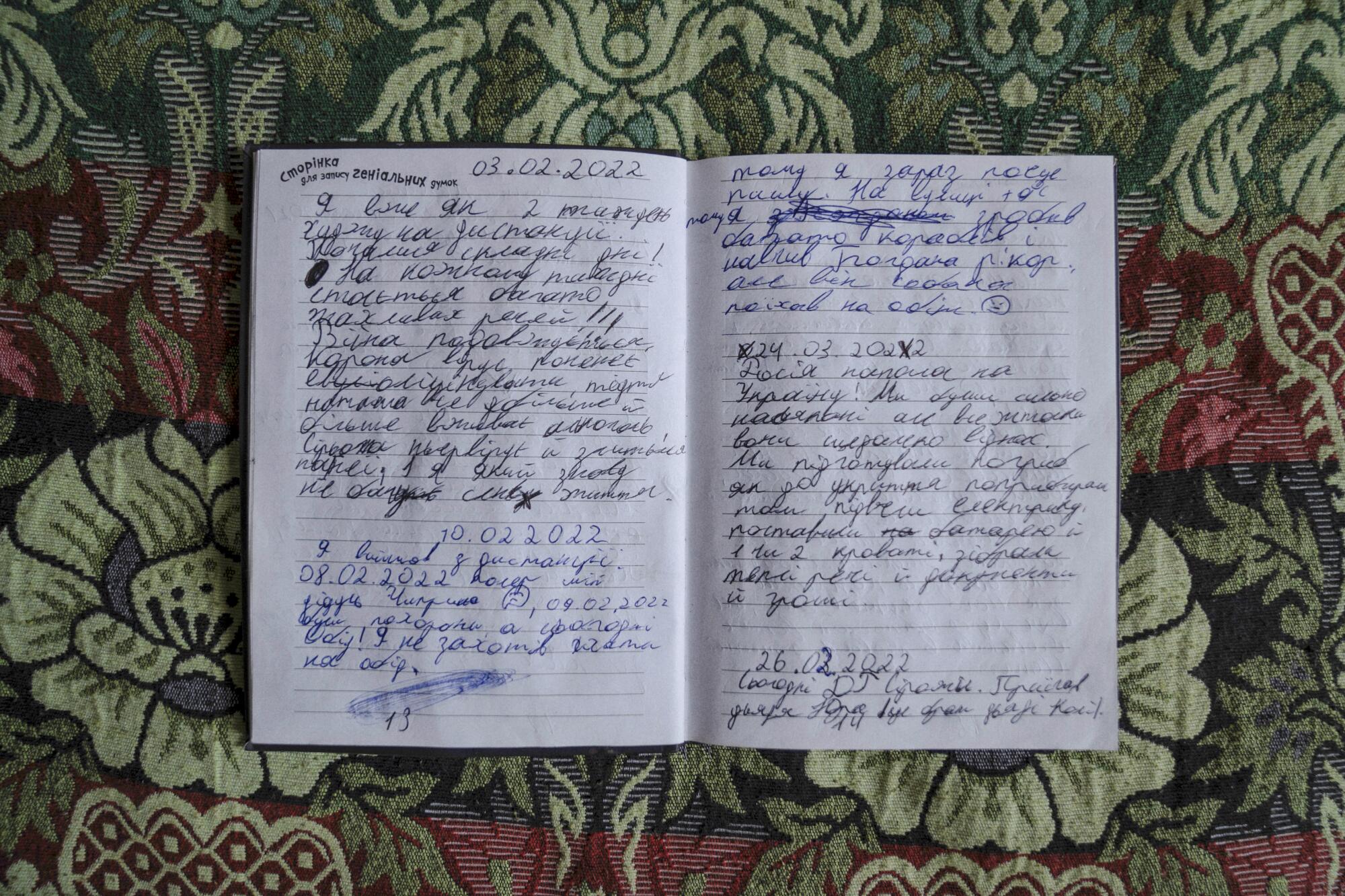

There was a special girl, Yarina, he wrote, but she ignored him. He loved the video game âMinecraftâ and the familyâs half-wild cats. He grumbled occasionally about his mischievous 6-year-old half brother, Seraphim, who did not always live up to his angelic moniker. When his stepfather drank, it worried him.

Those boyhood musings were interrupted by a terrible noise in the sky on Feb. 24. Tens of thousands of Russian troops rolled across Ukraineâs borders, and suburbs of the capital, Kyiv â including Tymophiyâs farming village, Shevchenkove, some 30 miles to the northeast â were quickly overrun or menaced as the fighting drew near.

âYesterday in the morning there was an air raid alert. You could hear in our village how planes were dropping bombs,â Tymophiy wrote in a journal entry dated March 3. The family â he; Seraphim; his mother, Yulia Vashchenko, 37; and his stepfather, Serhii Yesypenko, 43, known as Serozha, hid in the cellar.

The parents began talking about trying to leave. But to where? They hesitated.

On the morning of March 8, less than two weeks into the war, the couple slipped out without waking the boys. The village market, a short distance away, was still open, and they needed the extra money they made by selling tea and other dry goods there.

After a few hours, Tymophiy wrote later, his mother called him. She was frantic. Russian armored vehicles were rumbling through the villageâs narrow lanes. She told him to grab Seraphim and hide in the bathroom. He didnât know it then, but it would be their last conversation.

A bit later, Tymophiyâs aunt and uncle â Olena Streelets, 47, called Lena by family members, and her husband, Serihy Provornov, 63 â arrived and hurried the boys to their nearby house. They told the brothers that their parents had been called away to Kyiv, but that fighting made it impossible for them to return just now.

Tymophiy, whose full name is being withheld because he is a minor, was worried but not unduly so. The rush of events â the thunder of artillery, Seraphimâs antics, settling into their aunt and uncleâs cramped home â kept him distracted.

âI have gotten used to shells flying over my head,â he wrote on March 13. âWe still donât have electricity.â

More days went by, and Lena and Serihy made excuses over Yulia and Serozhaâs absence. It was Seraphim â the unnoticed little eavesdropper, overhearing low-voiced, anguished adult conversations â who blurted out the truth.

Tymophiy raged to his diary, his fury at first overwhelming his grief. In slashing red ink, he drew a horned devil with angry darts shooting from its eyes.

âI found out what happened to my mom and Serozha,â reads a March 14 entry, nearly a week after the deaths. âThey were killed!â

His aunt and uncle had held back yet more unbearable news. The bodies of the couple â who died from large-caliber fire aimed nearly point-blank at their car by a Russian tank â lay mutilated, unretrieved and alone inside their silver Opel Vectra for three days while Tymophiyâs uncle tried to negotiate safe passage to collect the remains.

Like hundreds of other civilians killed by Russian troops in the once-placid Kyiv suburbs â many people slain execution-style, some corpses bearing signs of torture â Yulia and Serozha had to be buried temporarily in makeshift graves. Theirs was near a garden gazebo.

Shelling shook the village for nearly three more weeks, before the Russians pulled back as abruptly as they had come, abandoning their bid to seize the capital and regathering in the east.

The family wanted a proper funeral, but it had to wait for an exhumation and examination by forensics experts and investigators, who were collecting what was rapidly becoming a mountain of war crimes evidence. More than 1,300 bodies were recovered in the capital region alone. Russia continues to deny its troops deliberately targeted civilians.

Finally, among more than a dozen other fresh graves, the two were buried side by side in the village churchyard on April 12.

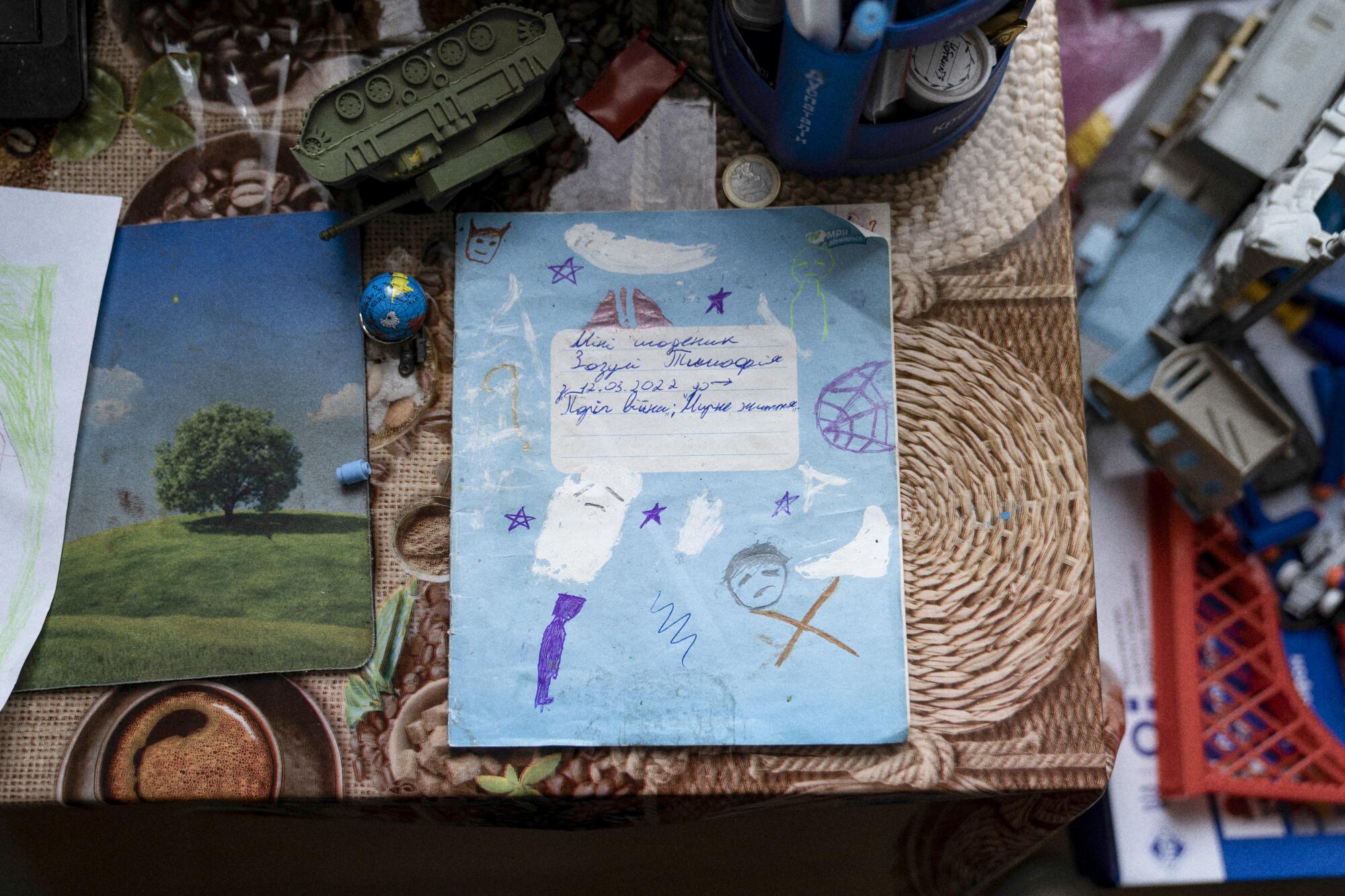

In the margins of his journal, its blue cover now decorated with drawings of a pair of ghosts and a boyâs sad face, Tymophiy wrote: âDreams do not come true.â

--

The war in Ukraine has been uniquely horrific for its children. About one-third of them, more than 7.5 million youngsters, are displaced from their homes, according to United Nations estimates. At least 348 children have been reported killed as of mid-July, Ukrainian officials said, but those numbers, which do not include an accounting from still-occupied areas, are acknowledged to be low, probably dramatically so.

Itâs as if childhood itself has been scoured away and something terrible has taken its place.

âI would say that every single child in Ukraine, their lives have been touched by this war,â Afshan Khan, the regional director of UNICEF, the United Nations childrenâs agency, told reporters at the world body in June. âTheyâve either lost a family member, or they have ... witnessed trauma themselves.â

In a brutal conflict heavily documented on social media and in news photographs, there was some reticence at first over circulating images of tiny corpses.

But now, nearly six months on, war and outrage propel endless online postings of disturbing photos and videos: pictures of dead children beside their dead parents, kids bandaged and bloodied in hospital beds â if they are lucky enough to make their way to one â little ones wailing and bewildered, or stunned and silent, as they are bundled into trains and vans carrying them away from the battle zone.

Sometimes, relatives who are exposed again and again to the sight of dead and maimed loved ones, especially the youngest victims, beg for a respite from the graphic images. But they keep coming.

Before the Russian invasion, Ukraine already had at least 100,000 orphans, many living in grim conditions in state care. Now their still-uncounted ranks have swelled. Family separations abound: fathers deployed to the battlefront while mothers and children seek shelter elsewhere. Whole families have been sent to âfiltrationâ centers in occupied Russian territories, with hundreds of children ending up inside Russia proper and put up for adoption, according to Ukrainian officials.

Every day at 8 a.m., Daria Herasymchuk, an advisor to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on childrenâs affairs, receives a recap of the previous dayâs events, including the latest on children killed, wounded, missing or believed deported. Or left motherless or fatherless, or both.

âItâs the worst moment of the day,â she said. âItâs every day.â

---

Lena said there was never any question that she and her common-law husband, Serihy â each on their second marriage, with adult children who long since left home â would take in Tymophiy and Seraphim. But itâs an overwhelming task.

Their run-down house consists of three tiny rooms: the bedroom, kitted out with new bunk beds for the boys; a living room with peeling paint where the couple now sleep on a double bed that also serves as the only sofa; a smoke-stained kitchen with a shower crammed behind a plastic curtain.

Serihy is working on a cinder-block addition, but for now, the yard is strewn with construction debris, and just outside the entryway, a hole in the ground is covered over with rickety boards.

Seraphim is in perpetual motion. He leaps onto the sofa bed demanding to be tickled, drags around a watering can nearly as big as him, rolls around on the floor, waving his feet in the air. He giggles and shrieks, but though seemingly thirsty for attention, he is far less verbal than most children his age.

âWe have to take shifts with him,â said Lena, a former kindergarten teacher, ruffling his hair.

Tymophiy, towheaded like his brother, has a sloping visage that foretells a blunt-faced manhood. He can appear simultaneously childlike and old, with pale eyes often either downcast or fixed in an unsettlingly intense stare.

His main hobby these days is collecting âfragsâ from village lanes and yards â heavy, jagged bits of shell casings and rockets, which he likes to thrust into visitorsâ hands.

The family is receiving some government support, including regular sessions with a counselor for both boys. But Tymophiy scowled when asked about his sessions with the therapist.

âThere are plenty of things I donât tell him,â he said, looking away.

He doesnât sleep well, he said. Sometimes he thinks he sees eyes watching him in the dark. The early summer light bothers him. He wakes up tired; at night, he must comfort Seraphim when he cries out.

This is the boysâ home now â but perhaps only for now. The sisters of Tymophiyâs stepfather, now estranged from Lena and Serihy, have moved into the family home a few streets away. They want to adopt Seraphim, their blood relative, his aunt and uncle said.

Lena and Serihy are adamant the boys should not be separated, and want to keep both of them. But the situation is complicated by family acrimony, missing documents and the unknown fate of Tymophiyâs father, who has not been heard from in years.

Tymophiy picks up his diary only sporadically now, he said. He sometimes writes in what he describes as a private code, and makes other entries in invisible ink. He willingly shows off the volumes but also declares angrily that the journals have brought him too much attention. Once a constant and a comfort, the diary-keeping has turned as strange as the upside-down world around him.

âSometimes I just want to burn them!â he said.

In the village, some aspects of normal life are beginning to resume. Flowers poke up through rubble. There is talk of school starting at some point. The market near where Yulia and Serozha died is open again.

Some of the family cats disappeared during the fighting, but others made their way home or were born weeks later. Tymophiy scooped up a limp-looking gray kitten, nuzzling it. That helps him sleep, he said.

Lena, a decade older than her dead sister, tears up when she reminisces about Tymophiyâs mother, although she does so only if she is out of his sight and hearing. Yuliaâs turbulent relationship with Tymophiyâs father nearly broke her, in the elder sisterâs telling. He abandoned her when the boy was still a baby.

But as a single mother still in her 20s, Yulia rallied and finished her education in Kyiv, Lena said. She got together nearly a decade ago with Seraphimâs father and moved back to the village, and the pair rejoiced six years ago over the birth of a baby, Seraphim.

Lena was godmother to both boys. Years ago, she would take Tymophiy to school on the back of her bicycle or, when he was small enough, snuggle him right into the front basket, where the breeze on his face made him laugh.

In her sisterâs place, she said, she would do her best to mother them.

âWe were family, even before this war,â she said. âNow we will try to be a new kind of family.â

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.