Emmett Till’s home is one of more than two dozen Black sites to get preservation funds

CHICAGO — Emmett Till left his home on Chicago’s South Side in 1955 to visit relatives in Mississippi, where the Black teenager was abducted and brutally slain for reportedly whistling at a white woman.

A cultural preservation organization announced Tuesday that the house he had lived in with his mother will receive a share of $3 million in grants being distributed to 33 sites and organizations nationwide that are important pieces of Black American history.

Some of the grant money from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund will go to rehabilitate buildings, such as a bank in Mississippi founded by businessman Charles Banks; the first Black Masonic lodge in North Carolina; and a school in rural Florida for the children of Black farmworkers and laborers.

The money will also help restore the Virginia home where tennis coach Dr. Robert Walter “Whirlwind” Johnson helped turn Black athletes such as Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson into champions; rehabilitate the Blue Bird Inn in Detroit that is considered the birthplace of bebop jazz; and protect and preserve Black cemeteries in Pennsylvania and on a tiny island off South Carolina.

Brent Leggs, executive director of the organization, which is in its fifth year of awarding the grants, said the effort is intended to fill “some gaps in the nation’s understanding of the civil rights movement.”

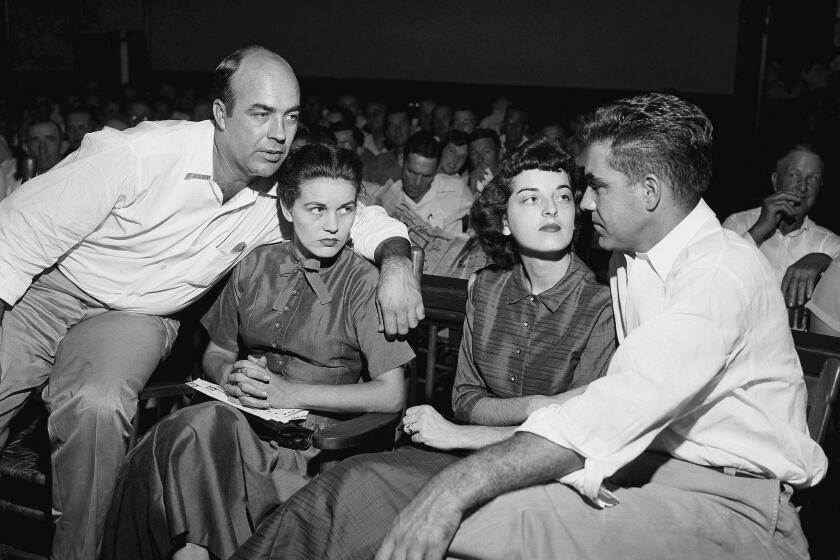

In the manuscript, Carolyn Bryant Donham insists she didn’t know what would happen to 14-year-old Emmett Till, who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955.

The brutality of Till’s slaying helped galvanize the civil rights movement. The Chicago home where Mamie Till Mobley and her son lived will receive funding for a project director to oversee restoration efforts, including renovating the second floor to what it looked like when the Tills lived there.

“This house is a sacred treasure from our perspective, and our goal is to restore it and reinvent it as an international heritage pilgrimage destination,” said Naomi Davis, executive director of Blacks in Green, a local nonprofit that bought the house in 2020. She said the plan is to time its 2025 opening to coincide with that of the Obama Presidential Library a few miles away.

Leggs said it is particularly important to do something that shines a light on Mamie Till Mobley. After her 14-year-old son’s lynching, Till Mobley insisted that his casket be open for his visitation and funeral, to show how his battered body looked when it was pulled from a river — to show the world what racism looked like.

It was a display that influenced thousands of mourners who filed by the casket and the millions more who saw the photographs in Jet magazine — one of whom was Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Ala., bus to a white man about three months later remains one of the pivotal acts of defiance in American history.

A team searching a Mississippi courthouse found the warrant charging a white woman in Emmett Till’s kidnapping.

“It was a catalytic moment in the civil rights movement, and through this we lift and honor Black women in civil rights,” Leggs said.

The news of the grant follows a recent revelation about the discovery of an unserved warrant to arrest the woman, Carolyn Bryant Donham, whose accusation led to the teen’s lynching.

Till’s Chicago home and the story of his open casket highlight the risks that the remnants of such history can vanish if not protected. The red brick Victorian built more than a century earlier was falling into disrepair as recently as 2019 when it was sold to a developer, until it was granted landmark status by the city of Chicago. And the glass-topped casket that held Till’s remains was donated to the Smithsonian Institution only after it was found in 2009 rusting in a suburban Chicago cemetery shed, where it had been left after the teen’s body was exhumed years earlier.

That discovery of the casket, which happened only because of a scandal at the cemetery, underscores how easily significant pieces of history can disappear, said Annie Wright, whose late husband, Simeon, was asleep next to his cousin Emmett the night the Chicago teen was abducted.

“We got to remember what happened, and if we don’t tell it, if people don’t see [the house], they’ll forget — and we don’t want to forget tragedy in these United States,” said Wright, 76.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.