Seattle is boarded up. This artist has made plywood his canvas

SEATTLE â When most people look at the thousands of sheets of plywood that encase storefront after storefront in Seattle, they see a city ravaged by coronavirus lockdowns and break-ins.

Malcolm Procter sees a canvas.

Last week, the 32-year-old street artist and clothing designer dipped a brush in white paint and considered the plywood that covered a shattered display window at Nordstromâs downtown department store.

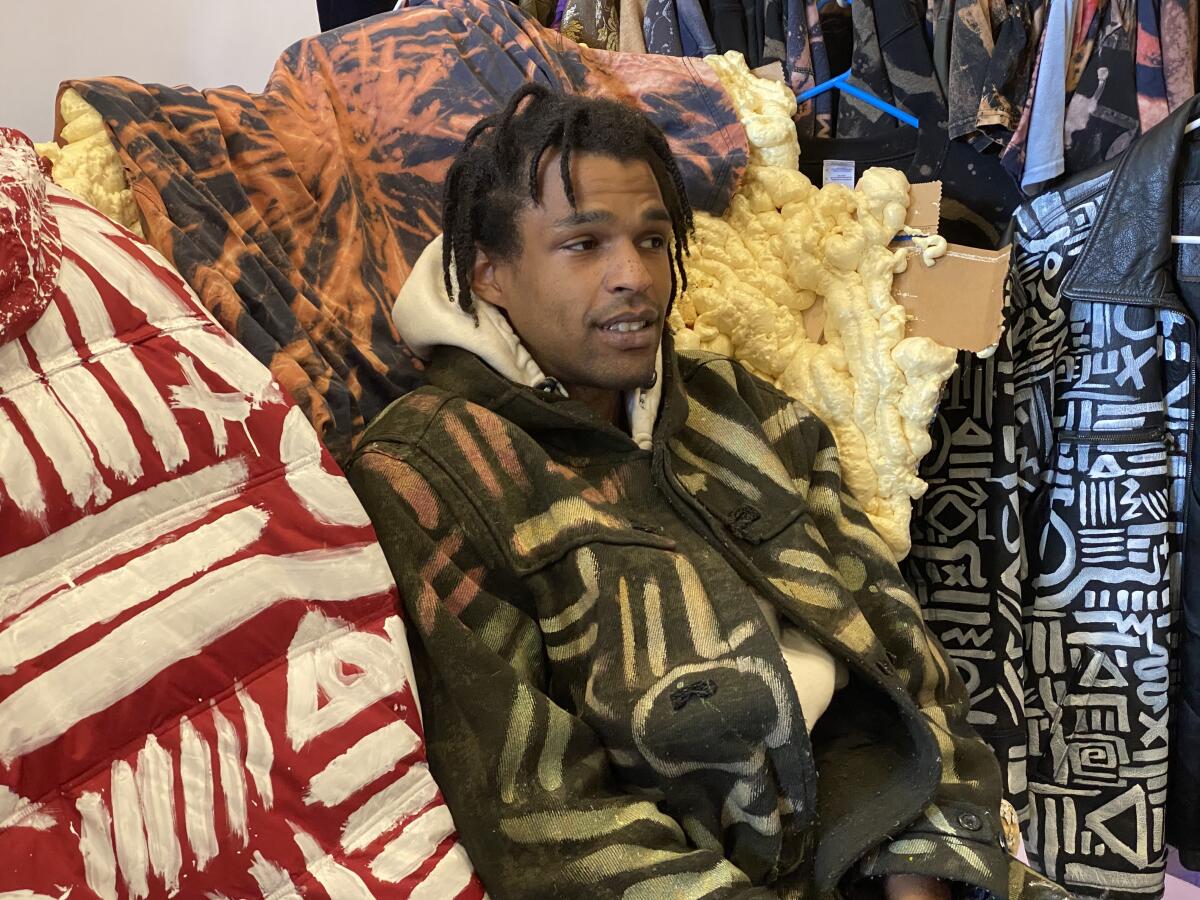

Soon, Procter filled the expanse â about the size of a cinema screen â with lines and squiggles. The distinctive patterns matched shapes bleached into Procterâs cap, coat and pants, camouflaging the 6-foot-1 dreadlocked artist atop a step ladder as a mural emerged.

âNever did I think Iâd get a canvas like this,â he said. âThis is a dream spot for sure. Iâm going to bring my grandma out.â

Procter has joined an assortment of artists trying to paint Seattle back to life.

Some of his works, including the Nordstrom mural, are commissions that come with stipulations â in this case, no words or overt political messages. Others have been passion projects on panels he claimed before other artists could get their brushes on them.

Thousands of boards are still bare, but everyone from graffiti taggers to would-be Picassos are claiming locations fast.

âIâm trying to get as many spots as I can,â Procter said. âThis kind of painting is disaster relief.â

His most coveted piece wraps around the corner of a brick building in the Capitol Hill district. He has labored to defend it, first from taggers and then from activists known as Black Blocs.

âThe first time those people hit it, I found out who the dude was, and he was cool,â he said. âNext, the Black Blocs tagged it. Some people call them anarchists. But everyone is quick to call everybody anarchists.â

Braving tear gas, Procter worked amid violent clashes between protesters and riot police, who struggled to guard a precinct on the same block before boarding it up and leaving â yielding six blocks that have been dubbed the âCapitol Hill Autonomous Zone.â

Television coverage of the zone has included images of Procterâs shiny eight-foot-tall mural. It features his hallmark symbols in yellow, against broad horizontal stripes of red, black and green â the colors of the Pan-African movement, which seeks to strengthen solidarity in the African diaspora.

Procter, who is African American, rarely gets more political than that. He said he shared outrage at the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police last month, but he has not marched in the ensuing protests.

On Sunday, he returned to dab white âstruggle flowersâ on the mural in the renamed Capitol Hill Organized Protest zone, as protesters and partiers milled about.

Born and raised in Seattle â his mom a postal carrier and his dad a Boeing test-flight computer programmer â Procter found his artistic sensibilities in graffiti, painting bridges, buildings, train cars and freeway ramps.

As a youth, he was caught among a group carrying spray cans and sentenced to 200 hours of community service.

As protests erupted over the killing of George Floyd, Angelenos honored his life with murals and street art, calling out racial injustice.

He fulfilled the obligation by signing up for the Washington Bus Project, which registers young voters, and then moved on to a variety of jobs â waiter, Seattle Opera extra, T.J. Maxx clothing sales clerk, assistant deejay, landscaper and head of a small commercial construction company.

After âlive paintingâ over the years beside nightclub bands and at private parties, he found his niche as a self-styled artistic entrepreneur.

Last year he joined other clothing designers opening a store in the Chinatown district, where heâs become a familiar character as he works on the sidewalk out front, bleaching patterns into clothing. His shapes and symbols evoke African mud cloth, a style of dyed fabric traditional in Mali.

Paul Nunn, projects lead at Urban ArtWorks, a nonprofit organization underwriting public works of art, said he sees people wearing Procterâs clothes around Seattle and follows his works on Instagram.

âHeâs totally found his mark,â said Nunn, who chose Procter for the Nordstrom project as part of a mural-painting initiative funded by the Downtown Seattle Assn.

Procter, a free spirit accustomed to a casual pace, was scrambling this week to fulfill all his commitments.

There was his own boarded-up storefront to paint, primed in purple to hold the spot.

Fortune Garden restaurant wanted him for a seafood-themed work across from one of his first plywood paintings, a non-commissioned four-panel display bearing the phrase âWe are aliveâ and âOhana,â a Hawaiian word meaning âfamilyâ in a broad sense.

Managers of two Chinatown community newspapers were reviewing his concepts in a competitive process, eager for depictions of young people reading the news.

Then there was the piece heâd promised the Louisa Hotel apartments, a portrait of Ernestine Anderson, the late jazz and blues singer whom his grandfather knew.

At the Nordstrom mural last week, Procter stepped back to review his progress. Climbing the ladder, he transitioned to sweeping blue and red brush strokes, outlining a peak resembling Mt. Rainier.

He worked on as darkness fell, spraying a gold streak on each white symbol surrounding the mountain. The spray paint glowed, illuminated from above by lights on a fractured plate-glass canopy. A golden circle stood out. Sun? Moon?

âIâm not sure yet,â he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.