âItâs too hard to live this yearâ: Chinaâs workers struggle with coronavirus unemployment

BEIJING â Zhang Junliang couldnât believe he was at the train station again.

He watched as Old Liu handed out tickets to five men squatting on the ground next to rolled-up blankets and dusty bags of belongings. Another $10.60 spent on top of the same amount theyâd paid for the previous dayâs trip from their village in Junxian county, northern Henan province, to Beijing.

âWeâll be home by five in the afternoon,â Old Liu said, squinting up at the schedule, red numbers blinking against a black LED screen.

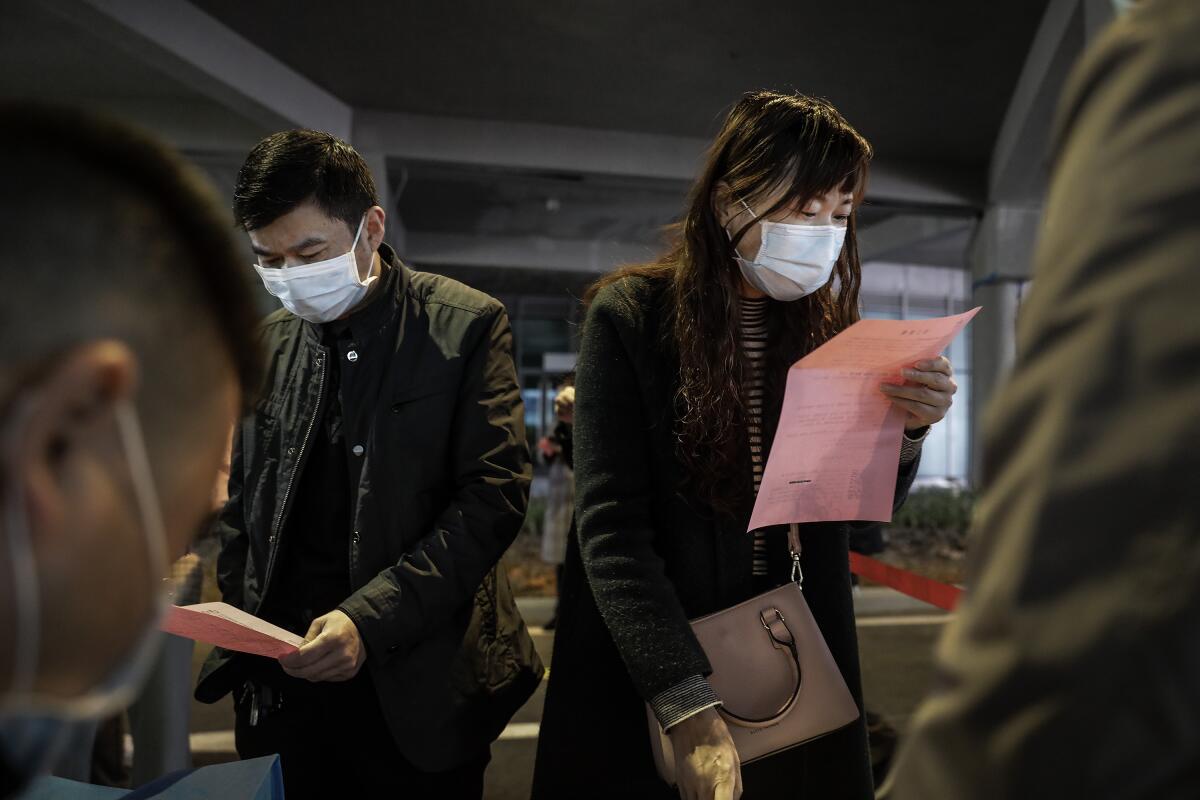

Zhang and Liu had come to Beijing with the others, hoping to get back to work after nearly three months of coronavirus lockdown.

Theyâd been promised salaries of $28 a day, plus potential overtime pay, for jobs in decoration â painting walls, installing plumbing, affixing windows â with on-site housing and meals provided.

But when they arrived, there was no work contract, no benefits, no time off. The boss said theyâd get $24 a day and no overtime. They were offered daily stipends of $2.83 for food.

There was another problem: They were migrants who hadnât fulfilled a required 14-day quarantine for anyone entering Beijing. That quarantine would cost at least $28 per day per person. If they wanted to look for other jobs, theyâd need to pay rent or hotel expenses after that. A cheap shared apartment would cost about $282 a month, Zhang calculated.

Such is the troubling math of a migrant. Might as well go home.

China is recovering from the coronavirus. Infection and death numbers are low, and lockdowns are slowly lifting. But the nation is coming to a reckoning with the costs of the deadly pathogen. Officials recently announced the countryâs GDP had shrunk by 6.8% in the yearâs first quarter, breaking a 40-plus year streak of growth in the worldâs second-largest economy.

It was a staggering admission for the Chinese Communist Party, which has vowed under Xi Jinpingâs leadership to double the size of Chinaâs 2010 economy and eliminate poverty by 2020. Both goals were questionable by the end of last year, when Chinaâs economy grew by 6.1%, the slowest rate in almost three decades.

The partyâs biggest concern right now, however, is not GDP size but unemployment, which set a record at 6.2% in February. It declined slightly to 5.9% in March, but experts say those figures donât include hundreds of millions of migrant workers like Old Liu and Zhang.

A recent analysis by UBS estimated the pain is spread across sectors: 50 million to 60 million service workers and 20 million in industry and construction were unemployed at the end of March.

Even if China manages to fully resume work at home, its factories will be affected as the coronavirus causes economies to contract worldwide, reminding Beijing that its fate is intricately tied to the strengths and vulnerabilities of other nations. The manufacturing sector, already hurt by the U.S.-China trade war, faces a plunge in orders and the risk of foreign companies shifting supply chains elsewhere. Japanâs government has taken the lead, spending $2 billion to help companies move out of China.

After five Nigerians living in Guangzhou, China, test positive for the coronavirus, a campaign targets all Africans in the city.

Jobs and basic livelihoods are now the bedrock of the Communist Partyâs legitimacy. The State Council has called for an extension of welfare payments to some migrant workers.

Small protests have broken out across China: shopkeepers demanding rent cuts, construction workers protesting unpaid wages, taxi drivers asking for suspension of cab rental fees, and hospital workers, who have been heralded as heroes in state propaganda, asking for months of delayed pay and promised but unpaid subsidies.

âSister, youâre dreaming too beautifully,â Zhang, 35, said, laughing, when asked if he was receiving any government help to cushion the blow of the coronavirus lockdown.

The sobering financial news and the travails of millions of workers like Zhang come as Chinese authorities have been trying to shift Chinaâs economy away from manufacturing and exports toward service sectors and domestic consumption. Some cities and provinces are distributing shopping and travel vouchers to stimulate consumer buying.

Chinese companies producing faulty testing kits and masks are marring Beijingâs attempts to assert leadership in the fight against the coronavirus.

The coronavirus economic measures have so far focused on keeping small and medium-size companies afloat by boosting lending, providing rent subsidies and tax breaks, and lowering employersâ contribution to pensions and insurance. Direct cash handouts have been minimal as individuals are largely left to the social security system.

But that system covers only a small fraction of workers and excludes most migrants, who often work without contracts and have been blocked from urban welfare systems because of the hukou system, which ties peopleâs access to social services to their rural or urban status from birth.

The government is attempting to ease the burden on workers, including by giving 67,000 jobless migrants the equivalent of $864 in a onetime cost-of-living payment. By the end of March, 2.38 million people had received unemployment benefits averaging $571 per person, according to official statistics. An additional 5.78 million people received small subsidies to combat inflation.

Such measures are a step forward, but fall short of covering the tens of millions of unemployed workers.

Old Liu, 51, who asked that his alias be used instead of his full name, said this was the third failed job-seeking trip heâd made since March. He has never had a formal work contract. He sought seasonal jobs in different places each year: Inner Mongolia last year, Beijing now, maybe Xinjiang next. He is a man of hopes and maps. Wherever the pay is good, he goes.

But the coronavirus made this year worse than usual. No one was paying as much as before. Travel had been impossible in the first few months of the year, and while middle and upper-class workers adapted to teleconferencing from home, grassroots workers like him watched their savings evaporate even as they tried to eat cheaper.

âItâs too hard to live this year,â Liu said, shaking his head.

It has been the same for Zhang. He has worked in 10 different fields already, he said, but never managed to find a stable income. He spent six months at a factory in Xiamen and tried sales in Guangzhou. This was his first time collaborating with Old Liu.

Zhang had been locked at home since January, watching the coronavirus news, hearing rumors that workers who went to help build emergency hospitals or fill other hard labor roles in Hubei province made huge sums, sometimes more than $200 a day.

But he hadnât gone. You could never be sure back then whether you might get the virus or not â and his village was quarantined anyway.

A recent survey of 726 villagers in seven rural provinces outside Hubei by Stanford Universityâs Rural Education Action Program found that almost all had stopped working for a full month after quarantines began, largely because their workplaces closed and travel was restricted. That meant a loss of $100 billion in rural migrant worker wages nationwide in just one month of the coronavirus lockdown.

Workers like Zhang are not alone in their suffering. In the first quarter of this year, the number of available white-collar jobs dropped by 27% compared with the same period last year, according to a recent analysis of online job postings by Peking Universityâs Guanghua School of Management.

Mo Li, a 37-year-old in Shanghai, wrote on social media that sheâd stopped buying anything but food and cat litter since she lost her job. She ate instant noodles and took showers at the gym to save money for her $536 monthly mortgage. Sheâd recently submitted her resume for 117 jobs and heard back from only two firms.

Another user in Beijing wrote that her parents, both in their 50s, had recently lost their jobs. Her father was now driving a borrowed car for Didi, Chinaâs equivalent of Uber, and making $28 a day. They owed tens of thousands of dollars, and her parents cried when they received daily calls from debt collectors.

âI come to work each day, but I feel like my heart is being fried in oil,â wrote Zhu Junyong, a traditional Chinese medicine doctor who said few patients meant pay cuts and potential layoffs at her clinic. âYou never know when the knife will fall on your head,â she said.

Zhang knew little of the white-collar world. He stared out the train window, wondering if heâd been too ambitious for his own good. He wouldnât qualify for the new welfare payments because he wasnât below the local poverty line of $601 a year. He could make that much in a month, as long as he hustled, and he wanted to surpass that threshold.

But then again, he hadnât worked since before the coronavirus. At the train station, facing the prospect of going home with even less than he arrived with, he nodded as one of the other Henan workers said: âEverything we do is just for survival.â

Zhang took out his phone and filmed the clouds, the sky, the city road becoming a blur as his train moved away from the station. âGoodbye, Beijing,â he murmured.

An attendant asked to take his temperature. The passing trees waved in the wind.

Gaochao Zhang and Nicole Liu of The Timesâ Beijing bureau contributed research to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.