He was seeking custom-made boots. The journey led to a life deeply touched by love and death and leather

- Share via

VERNAL, Utah — All my life I’ve looked down upon them.

How could I not?

Cantilevering from my legs like architectural wonders of the world, they’re unavoidable. No mere foundation, my feet are declarations, emphatic dots at the base of a 6-foot, 5-inch exclamation point.

I stopped measuring them years ago. 14s? 15s? 16s? Narrow? Super-narrow?

Bring me your longest and narrowest shoes in stock, I’d tell the department store clerk, who would emerge with some dusty pair from a forgotten corner of the backroom. If they fit, I’d inquire about the inventory.

Italian leathers? Nope. High-top kicks? Nope. Crocs? Get real.

Like a breakaway republic, my feet seceded years ago, and the peace we’ve kept has never been easy. I once trekked through the wilderness of Montana, 111 miles in 10 days, in a pair of hiking boots that I thought would fit. In the end, my feet looked like relics from the battlefield of Verdun: blisters, moleskin and duct tape.

After years of discord, I decided to strike a détente. Instead of forcing my feet into ill-fitting shoes like some arranged marriage, I set off in pursuit of true love. I would buy a pair of custom hiking boots.

My journey began in March on a plane to Colorado, a connector to Utah, and a rental car to the doorstep of one of the country’s preeminent boot makers. Randy Merrell, who lives just outside of Vernal, assessed and measured, sketched, cut, stitched and nailed leather to soles to connect me with this dream.

For 10 days, he played host to me and my wife and on evenings invited us into his home, where we warmed ourselves in front of a wood-burning stove as he told us his story.

More than a boot maker, Merrell, 68, is something of an armchair theologian, and we listened carefully to the mysteries of a life deeply touched by love and death and leather.

::

Philosophers say that eyes are the gateway to the soul. I would argue it’s the feet, this strange collection of ligaments, tendons, muscles and bones, partners in evolution from a knuckle-dragging past to four-minute miles.

Feet have a talismanic hold on our psyches. Reflexologists manipulate them, and inquisitors flog them. Parents play piggy with baby’s toes, and lovers suck on them.

Still, so far from our brains and so close to our hearts, they bear our weight and carry us forward, but they weigh us down. Itchy, sweaty, lumpy, they contract fungus, develop hammer toes, bunions and corns. They attract sock lint, and they sweat.

So when Merrell, who is an elder in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, took my feet in his hands, I wanted to flinch. He was a stranger, after all. But I was surprised by the thoughtfulness of his touch.

Neither the size, the narrowness, the fallen arches, emerging bunions, an odd callus or two, Morton’s toes (second toes longer than the firsts) nor — what is certainly a sign of evolutionary progress — the absence of baby toenails put him off. He simply remarked at how flexible they were and seemed stumped.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” he said.

::

Merrell’s journey as a boot maker began when he was a teenager and saw a pair of Tony Lamas in Salt Lake City — brown-lizard wingtips, pointed toes, buck stitching, burgundy uppers and one-and-quarter-inch heels — and he was smitten.

But his father, a hard-bitten soul, said no, forcing Merrell to skimp and save and lay out the $67 himself.

Merrell and his father had a difficult, if not entangled, relationship. “If I did 98 things right,” Merrell said, “I’d get disciplined for the two that were wrong.”

Still the two stayed close. “I worshiped the ground the man walked on,” Merrell said.

As a teenager, he helped run the family farm in Vernal — 40 acres with Arabian horses — and among his chores was a monthly trip into town to get his father’s shoes repaired. The old man had a clubfoot — divine punishment, or so he believed, for his parents’ conceiving him before they were married.

That’s one way of understanding why Merrell became a boot maker. More than a trade, it is a devotion, a remedy and an act of atonement for a man he struggled with.

The next stop in Merrell’s journey was the town of Apucarana in Brazil, where knocking on doors was considered rude. So Merrell, on a mission for the church in the early 1970s, clapped his hands in front of a shoemaker’s home, and Pedro Barrato welcomed the 20-year-old Mormon inside.

Barrato was a “magician,” said Merrell, who watched as the shoemaker, working with a saw blade, cut pieces of leather by hand. His only machinery was a buffing machine and a sewing table with a treadle. Merrell paid $13 for a pair of Barrato’s calf-high, black-leather boots with heels made from airplane tires.

Once home, Merrell boarded a Trailways bus for Denver and an Amtrak coach car to Boston, where he enrolled at the Lynn Independent Industrial Shoemaking School and learned the finer points of pattern making and machine maintenance.

On New Year’s Day 1975, he hung a silhouette of a boot out in the frontyard of his father’s house and waited for customers.

::

The late-winter landscape of eastern Utah was beautiful and severe when we visited. Fields lay buried under a blanket of snow, a sea of whiteness buoyed by scattered farmhouses.

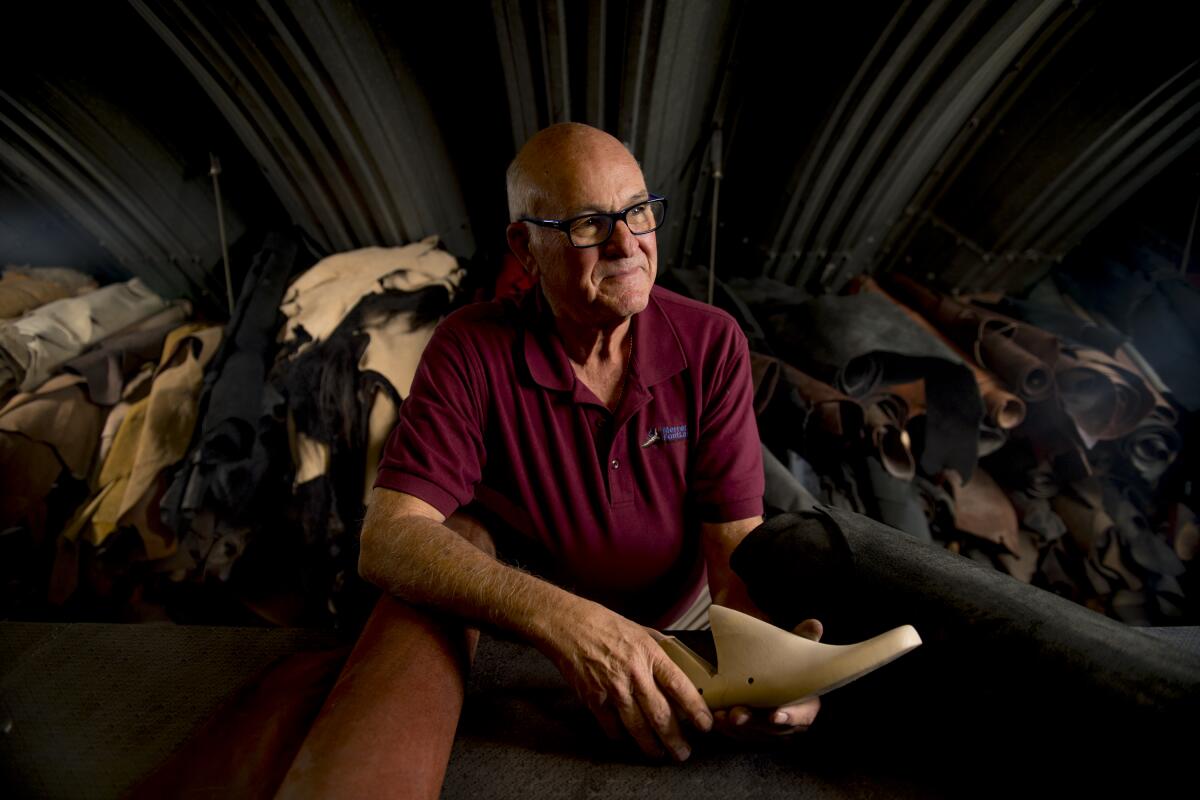

Each day, I drove west out of town on the straight-arrow roads of the Maeser township to watch my boots take shape at Merrell Footlab, three miles from the turnoff for Dryfork Canyon. Farther up the road is the cemetery where Merrell buried his son Luke, his wife, LouAnn, and where one day he too will reside.

Merrell’s workshop and home are earth shelters, large Quonset huts covered with concrete, rebar and 3 feet of earth. Deer, driven by hunger, browsed the dry grass growing on the roofs. Honking Canada geese banked through the valley.

Merrell could never imagine living anyplace else, nor has he had to. The world has come to him. Initially it was for his Western boots with their exotic leathers and fancy stitching — but then one day, reading Backpacker magazine, he saw the potential for a market that had been dominated by heavier and stiffer European styles.

He began developing hiking boots better suited for American terrain, and in 1981, he wrote a seven-page feature on selection and fit. Soon after, the phone rang.

Two entrepreneurs from Vermont wanted to make a deal, and with their backing, the brand — Merrell Boots — was born. What began as a backyard garage business became in two years a multimillion-dollar enterprise.

But the Faustian bargain that he struck with the investors couldn’t be sustained. Often traveling for work, Merrell was becoming a stranger to his wife and their four young sons, and after five years, he walked away. Today, Merrell Boots is a subdivision of Wolverine World Wide, and Merrell has no formal relationship with the company.

With LouAnn’s help, he began to ply his trade on a more modest scale, conducting boot-making seminars and expanding into orthotics. Soon customers started coming to him from all over.

Most arrived with feet that all the Foot Lockers and Boot Barns in America could not help — the undersized, the oversized, those damaged by industrial accidents, those with congenital maladies — and Merrell helped them find their way.

“At first, I just wanted to make nice boots, but all these problems came in through the door,” he said. He couldn’t ignore them.

There are other custom boot makers in the country — half a dozen or so by the internet’s accounting — but Merrell makes no claim for their ability to provide podiatric care. He prefers not to talk price until he has made a consultation. Every foot is different, and my estimate — in the thousands — was a measure of my uniqueness.

By the end of the first day, he had studied my leg lengths and stride. He had traced the perimeter of each foot, measured them in five places, and he had found the number and letter to describe them.

The average shoe size in America for men is 9D.

Mine were 17AAA.

::

Merrell often uses the word “magic” to describe his work, and I understand why. Building custom shoes is an exercise in shape-shifting.

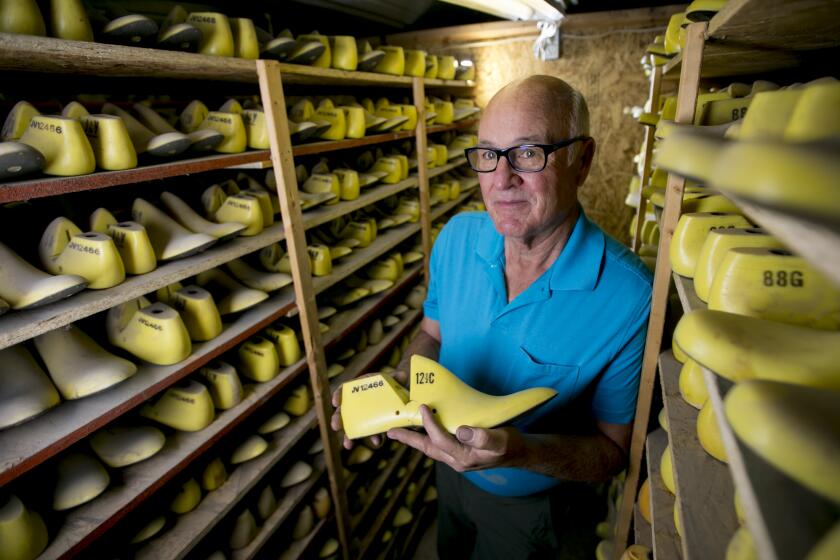

It begins with the last — rim shot, please — an easy joke among shoemakers. In their trade, a last is a precise model of the foot that replicates its length and width, its protrusions and hollows.

From the last, Merrell develops paper patterns. Then he cuts the leather, stitches the pieces together, stretches it over the last and adds the soles. From foot to shoe, he waves his wand, turning three dimensions into two and then into three again.

Unlike other garments whose looseness can be remedied by a belt or safety pin, a shoe is less forgiving. Not only must it fit, but it has to be durable. Merrell does the math: If you weigh 200 pounds and take 10,000 steps a day, you’re putting 1,000 tons on your shoes daily.

Standing amid workbenches and sewing machines, belt sanders and hand tools, Merrell began building my boots, helped by Preston Barker, 24, who started working here as an apprentice two years ago. Barker had been delivering household appliances and jumped when Merrell offered him the job.

Had he not, Merrell claims, the business would never have survived.

::

One Sunday I joined Merrell for the weekly sacrament meeting at his church, and during a small breakout session, the conversation shifted to the role that misfortune plays in life.

A woman shared the story of visiting a neighbor with a steep driveway. Snow had fallen, and her truck slid on the grade until she filled the bed with wood. The message was clear, especially to Merrell.

“We need a burden to progress spiritually,” he said.

His burdens started to accumulate almost 35 years ago.

The business was taking off, and he had started construction on the earthen structure that would become his workshop. One afternoon in November — with the shell of the building completed — his father was building up the layer of soil on the roof when the bulldozer he was driving broke through. He died of a fractured skull.

Twenty-two years later, Merrell was in the fields when LouAnn called him in. There had been an accident at the White River Bridge where their son had gone rappelling. A knot had slipped, and Luke had fallen. Merrell and LouAnn arrived just before the paramedics and found the 24-year-old “in a puddle of blood.”

Two years ago, he and LouAnn were hiking in the Grand Canyon with a daughter-in-law and her teenage son, Jackson. They were crossing Tapeats Creek, and the water came to mid-thigh. They had their hiking sticks and were holding on to each other’s backpack straps.

Then someone slipped, then another. When Merrell fell to his knees, he looked up to see LouAnn and Jackson carried off by the current.

Neither survived.

“I’m probably more broken than I look,” Merrell said.

Yet grief is not something he shies from. He speaks freely of it to those who will listen.

“When I was young and working on my father’s ranch,” he said, “I learned early on that the closer you stand to the horse, the safer you will be from its kicks and bites.”

::

Feet and faith have long carried pilgrims through life, and they have sustained Merrell on his journey as well. What happened at Tapeats Creek was as terrible as the aftermath was extraordinary, and his faith has given him the understanding and strength to explain the unexplainable.

“Where there should have been screaming and shouting and frantic terror, there wasn’t,” Merrell said. It was as if someone had pulled a veil over his eyes and “an umbrella of calm” came over him and his daughter-in-law, Julie, and he knows why.

During that dark night in the wilderness before the helicopter arrived — and four days of searching began — his father and Luke came to them. To ease their final breaths, Luke’s spirit joined LouAnn and Jackson. To provide comfort and solace, the spirit of Merrell’s father stayed with him and Julie.

“I just know,” Merrell said, tapping his chest, “that it was my father.”

His conviction is supported by a church where the scrim between earth and heaven is easily parted and couples once sealed are reunited in heaven. Life is not a series of random occurrences but filled instead with signs for those willing to see.

He knows many will say his beliefs are a mask for pain, fear and doubt, but that hardly matters to him. Like Job, he doesn’t ask why he carries this burden. He just knows that his faith allows him to find meaning in these losses, to know that the dead walk among the living and guide them in their encounters with the world.

To dismiss that is to steal the solace that he has found and to discredit what many others in pain desire.

::

On the day that Merrell finished my boots, I tried them. Standing in his workshop, I felt something new pass through me. Instead of making a joke — an easy reflex about these feet of mine — I felt a touch of sadness and joy as if I had finally been allowed to accept what I have.

Two days later, Merrell took us for a drive. We headed east out of town toward the Green River for a hike. The rolling plateau was so pillowed in snow that from the car I thought we were flying over clouds.

We arrived at the Jones Hole Fish Hatchery, and in the parking lot, I laced up my boots, the signature blue laces a counterpoint to the unscuffed brown leather. They were, in a word, beautiful, and as reluctant as I was to scuff them up, I eagerly awaited for the scars to appear.

The trail followed the east side of Jones Creek. Fishermen in waders fly-cast into the roiling water. We trudged through the snow that lay in patches on the ground, red dirt turning to mud.

The canyon is filled with box elders that had not yet leafed out, and above us sandstone cliffs soared like skyscrapers. Two miles down, we stopped to study pictographs of sheep, hand prints and swirls on the walls.

As we walked silently back to the car, I thought about acceptance.

As much as I have fought against the size of my feet, I realized that I wasn’t entitled to anything less. We can shake our fists at fate — be it a pair of unwieldy feet or a heart-wrenching loss — or we can come to understand that life follows no script, no set plan.

All we are responsible for is finding our own peace.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.