Commentary: Lose the All-Star game and lose big? That’s simply a big myth

- Share via

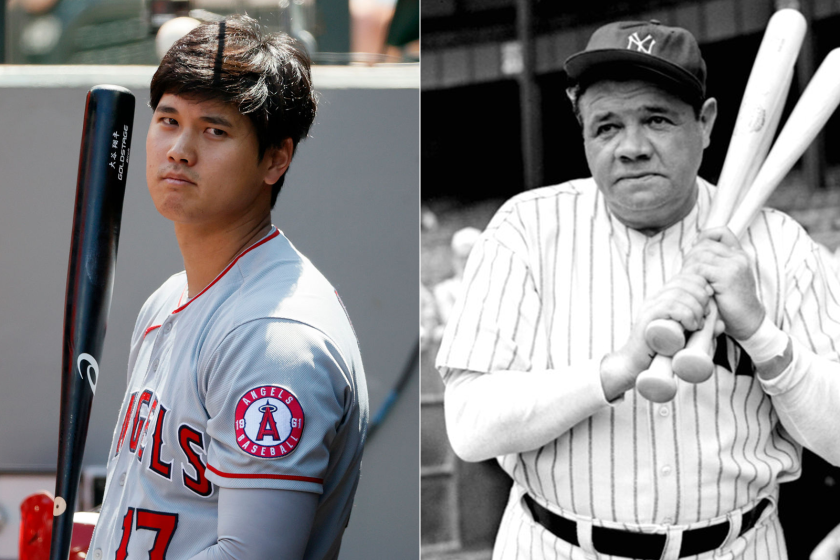

DENVER — On this day of the All-Star game, before Shohei Ohtani and his supporting cast take the field, let us engage in a bit of mythbusting.

And let us get right to the point: Despite a narrative concocted from one flimsily supported statement and amplified across the country, there is no evidence that the Atlanta area lost $100 million in economic impact when Major League Baseball relocated this year’s game to Denver.

On April 2, Commissioner Rob Manfred said the game would be moved, eight days after Georgia adopted a law that voting rights advocates say makes it harder for people to vote, and disproportionately so in minority communities. The United States Department of Justice since has sued Georgia over the law.

On April 3, the president of the agency that promotes tourism and travel in Cobb County said in a statement that the “estimated lost economic impact” of the relocation would be more than $100 million.

Sean Hannity repeated that figure on Fox News Channel. A conservative business advocacy group cited it in a failed lawsuit against MLB. Republican legislators echoed it in introducing a bill to strip MLB of its antitrust exemption.

“The league’s spineless decision to move the All-Star Game out of Georgia was based on lies told by President Biden and Democrats,” Rep. Buddy Carter (R-Ga.) said in a statement. “Now, it’s been estimated that this move will cause a loss of $100 million for the local community.”

Babe Ruth’s great-grandson loves what Shohei Ohtani is doing for baseball and for revitalizing the memory of baseball’s ‘Sultan of Swat.’

When I asked Carter’s office for the source of that estimate, a staffer cited the Cobb County tourism statement. When I left five messages with the Cobb County tourism office, asking for documentation to support the estimate, none of the messages were returned.

The original statement cited one supporting statistic: the cancellation of “8,000-plus MLB contracted hotel room nights.”

Georgia is lovely, but demand for hotel rooms there in July is not similar to demand for hotel rooms in, say, Hawaii in December. MLB would have gotten a nice corporate discount for those rooms and, given the time of year, let’s say the average league rate was $125 per night.

That would come to $1 million.

To be generous, let’s double that to $250 per night, and then let’s say everyone staying in those rooms pumped another $250 per day into the local economy — dining, shopping, entertainment, events and so on.

That would be exceedingly unlikely. An Arizona State study of the economic impact of the Cactus League — at a time of year when Arizona is a popular destination and hotels are expensive — found that the median daily spending for out-of-state visitors was $336 per day in 2020 and $405 per day in 2018. Both fell well short of our prosperous estimate of $500 per day, but, again, let’s be generous.

That would come to $4 million. Where’s the other $96 million?

The impact would have been more than $4 million, of course, because not everyone attending an All-Star event stays in an MLB-arranged hotel room. Tickets, concessions and merchandise from the game and accompanying events would have generated additional millions in revenue. But there is no evidence the economic impact would have been $100 million, or anything close to that.

“There is some loss, so it’s not zero, but it’s a whole lot closer to zero than the $100 million number Atlanta was throwing around,” Holy Cross economist Victor Matheson told the Guardian.

The Super Bowl delivers a significant economic impact, but the NFL produces a weekend event for tourists and high rollers. The league reserves 5% of tickets for fans of the local team.

The All-Star game is played in the middle of the week, with an emphasis on events for the host community. The league distributes roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of tickets to fans of the local team, depending on the size of the ballpark.

Max Muncy of Thousand Oaks High was the Oakland A’s first pick. Meanwhile, the Dodgers’ Max Muncy hit a walk-off homer. They share many coincidences.

Locals do not need hotel rooms, and they do not necessarily eat out the whole week.

Certainly, there are a fair number of tourists, some of whom bought tickets from locals, but the All-Star game is not tourist-driven. And, surely, the relocation of this year’s game is unfortunate for the businesses in the entertainment district surrounding the Atlanta ballpark that missed out on two or three days of parties and packed restaurants. But, if I live in Atlanta and would have spent $100 at one of those restaurants before the game, and instead I now spend $100 at a restaurant in my neighborhood, the change in economic impact to Atlanta is zero.

Economic impact projections can be notoriously fuzzy. In March, when Cobb County’s chief financial officer claimed in a memo that the impact of past All-Star games ranged from $37 million to $190 million, the memo did not cite the source of the figures. A county spokesman said the league provided the figures; MLB said it did not.

On Sunday, the Denver Post reported that local leaders say the All-Star game here could generate $100 million in economic impact. According to the Post, the president of the Denver tourism agency said the estimate was “actually borrowed from projections done for Atlanta.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.