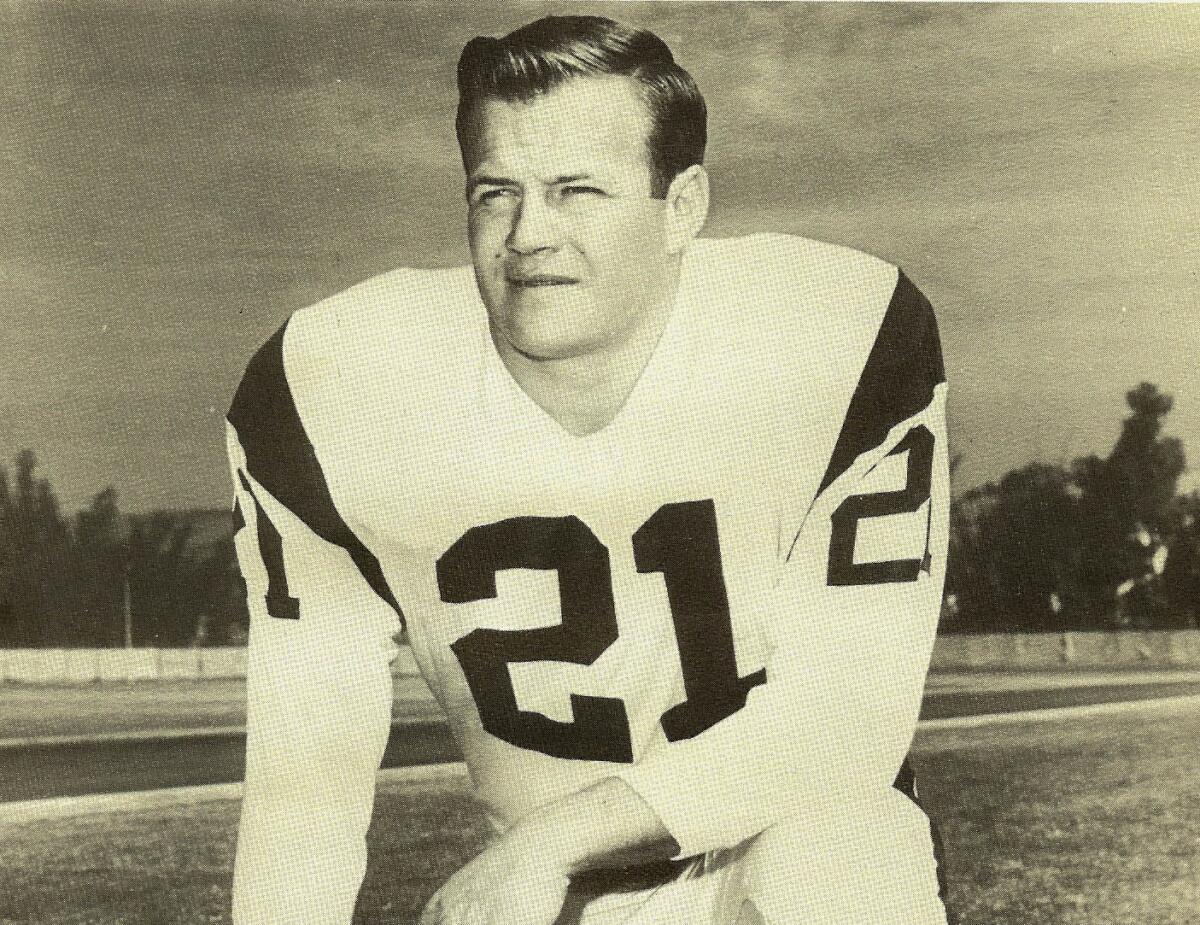

Eddie Meador, Rams defensive star who missed out on Hall of Fame, dies at 86

- Share via

Straightforward, matter-of-fact and knowing exactly what he wanted, that’s the way Eddie Meador lived his life. So upon graduating from high school in 1955, Meador drove 485 miles from Russellville, Ark., to College Station, Texas.

Meador walked into Coach Bear Bryant’s office at Texas A&M and said he wanted to play football for him. Bryant looked back at the 5-foot-10, 165-pound, tow-headed 18-year-old and told him he’d never play big-time football, saying, “You need to go somewhere else.”

Undeterred, Meador climbed back into his car and drove 437 miles to Tulsa, Okla., where a new coach, Bobby Dobbs, was taking over a Golden Hurricanes team that was 0-11 in 1954. Tulsa, Meador figured, was desperate. The school wouldn’t turn him down. But it did.

Meador returned to Russellville, enrolled at tiny Arkansas Tech and proceeded to start at tailback and safety all four years, breaking every school rushing record. The Rams drafted him and signed him for a $500 bonus in 1959 and he cracked the starting lineup as a rookie.

Every loss for the rebuilding Rams is a win this season. If they really want to build for the future, they need to set their sights on drafting Caleb Williams.

By the time his 12-year career as a cornerback and free safety with the Rams was over in 1970, Meador was a four-time All-Pro, made six Pro Bowls, was named to the NFL’s all-decade team for the 1960s and set Rams records that still stand with 46 interceptions, 22 fumble recoveries and 10 blocked kicks.

“Somewhere Bear Bryant is tipping that herringbone hat and saying, ‘You got me on that one,’” Meador’s son, Dave, said on a podcast.

Meador, who died this week at age 86, had only one lingering disappointment. Despite a pointed yet respectful years-long campaign by Dave, Meador is the only first-team, all-decade safety from 1960 to 2010 not to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Not making the Hall of Fame isn’t something Meador talked often about, although he did tell Jerry Crowe of The Times in 2009: “I probably was as good a ballplayer as some of the people that’s already in there. Maybe not, but I think that.”

Meador was born Aug. 10, 1937, in Dallas, and his family soon relocated to the tiny West Texas town of Ovalo, population 500, where Meador first played football in the seventh grade. The Meadors moved to another speck on the map, Atkins, Ark., before his sophomore year in high school and opened a laundromat in nearby Russellville.

In order to play football, Meador slept in a back room at the laundromat so he could walk to school. He broke his hip and sat out his junior year but came back as a senior to star at tailback. He also lettered in basketball and track and field.

He said he was motivated by “self-pride. ... I just don’t believe in doing anything less than my best, and I don’t like doing things the wrong way,” he said.

It was enough for him to believe he could play football at Texas A&M for the legendary Bryant, even though he was undersized. A few years ago Meador spoke to a high school class and said his biggest obstacle was “just having to prove to people that I could play.”

The only reason Arkansas Tech — its players were called the Wonder Boys — gave him a scholarship was “because one of my high school coaches had moved over to coach at Tech,” he said. By the time he graduated, he’d become the most wondrous Wonder Boy. He dashed 95 yards for a touchdown against the University of the Ozarks, rushed for 239 yards against Hendrix College three weeks later and amassed 3,410 rushing yards in his career.

During Meador’s senior year, a Tech coach happened upon a scout for the Rams in an Arkansas duck blind and told him he ought to keep the overachieving two-way star in his sights. Meador, who had bulked up to 193 pounds, attracted the attention of several NFL teams when he ran wild behind the blocks of left tackle John Madden in the Optimist Bowl, a postseason game in Tucson that pitted Division I All-Americans against Little All-Americans.

Gil Brandt, one of the architects of the Dallas Cowboys’ success in the 1970s and a Pro Football Hall of Famer, dies at 91.

The Rams took him with the 80th overall pick and he had no trouble contributing immediately to the struggling franchise. Assistant coach Jack Faulkner told a reporter that the fresh-faced rookie “looks like Mickey Rooney but hits like Jim Brown.”

Meador was in awe when he stepped onto the Coliseum field for his first exhibition, the L.A. Times Charity Game.

“I don’t think I heard anything from the coaches or players,” he said. “There was so much crowd noise that’s all I could hear.”

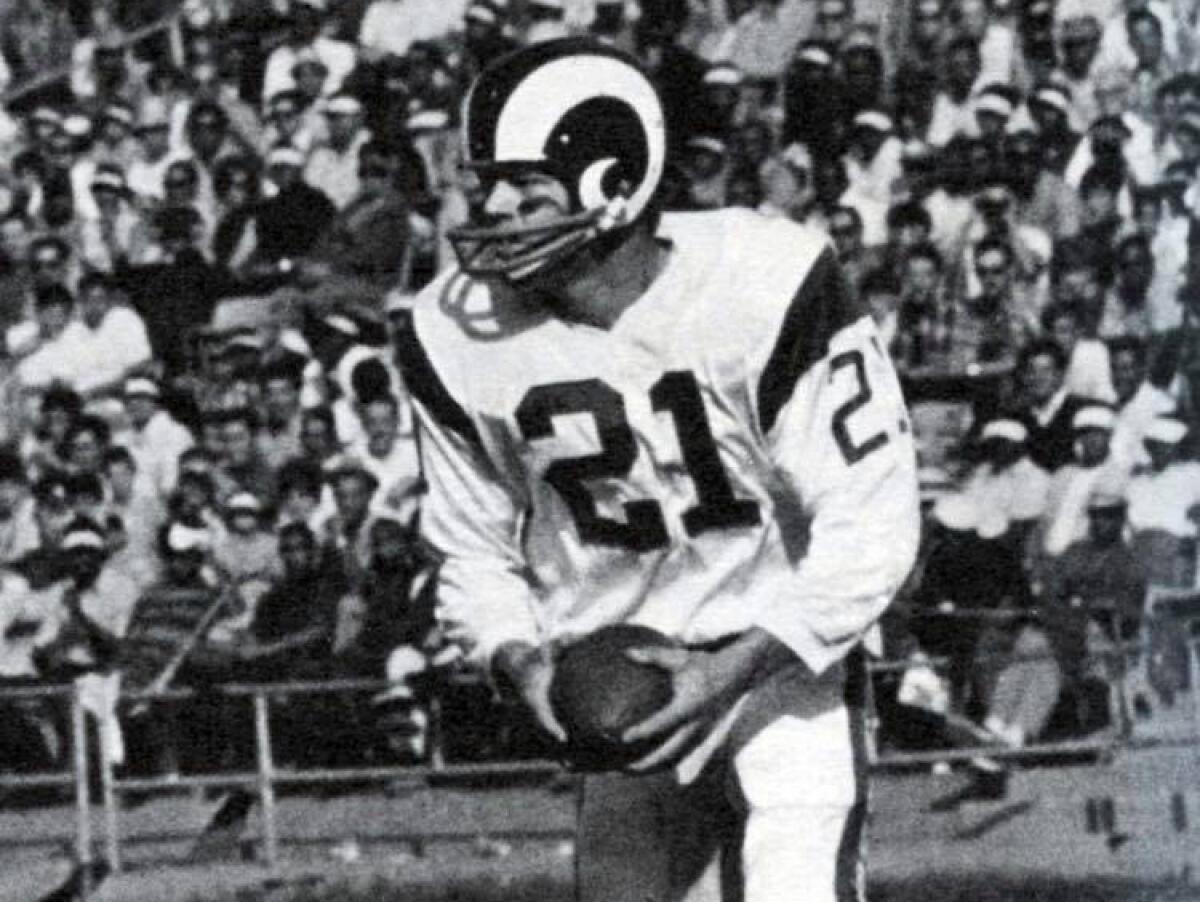

Despite the community support, the Rams went 2-10 and didn’t post a winning record until 1966 in coach George Allen’s first season. The next year they went 11-1-2, the first of three consecutive seasons of at least 10 wins. Meador had eight interceptions, returning two for touchdowns, and was widely considered the best free safety in football.

“Resourceful and inventive,” is how Allen described Meador. “He made plays you didn’t think he could make. He had real leadership qualities and captained the Rams for me.”

The Rams released a statement Tuesday: “We are deeply saddened to learn of the passing of an NFL great, Eddie Meador, who was a standout leader for our organization and the Los Angeles community throughout his entire 12-year career. He was an instinctive and fearless competitor who captained some of the greatest defenses in NFL history.

“Eddie’s ability to galvanize teammates made him a heartbeat of the Rams and his humility made him approachable to everyone. The Meador family and friends are at the core of our thoughts, and his legacy will live on forever.”

Meador’s eldest son, Michael, was born with cerebral palsy, and in 1969 Meador was recipient of the NFL Players Assn. Alan Page Community Award and the NFL father of the year award by raising awareness and funds for kids with special needs. That year, Meador also served as president of the NFL Players Assn.

Dave Meador said his father appreciated how much the Rams improved during his career. He especially enjoyed playing behind the defensive line of Deacon Jones, Lamar Lundy, Merlin Olsen and Rosey Grier, nicknamed the Fearsome Foursome.

“The hard times the Rams faced made him a better player,” he said. “He had to play smarter, he had to play harder. Playing against Jim Brown, Gale Sayers, the Johnny Unitas-Raymond Berry combination, Bart Starr; if you don’t pick up your game, you aren’t on the field.”

The closest the humble Meador came to bragging was when he recalled facing the rival Dallas Cowboys. He had three interceptions in one game and was named NFL defensive player of the week.

“Their quarterback seemed to like to throw the ball to me,” he said, chuckling. “Don Meredith would just throw it up and hope for the best. I liked that about him.”

After he retired from the NFL, Meador sold real estate in Dallas until the 1980s, when he and his second wife, Annette, launched an equestrian jewelry manufacturing company called the Gorgeous Horse after moving to Natural Bridge, Va., where they lived on 10 acres north of Roanoke in the picturesque Shenandoah Valley. The company is now run by Meador’s grandson Jason Maze.

Dave Meador launched a website several years ago, edmeador21.com, with the stated purpose to “promote the induction of Eddie Meador into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.” It includes testimonials from former teammates, including Olsen, who said Meador was not only “outstanding in coverage and a fierce tackler” but also possessed “a remarkable nose for the football that allowed him to come up with big plays again and again.”

Meador, who played in 159 consecutive games in his first 11½ seasons, was one of 12 semifinalists for the Hall of Fame class of 2024 when the seniors committee met Aug. 22, but the group instead chose Randy Gradishar, Steve McMichael and Art Powell. Dave Meador recognized that the rules for inducting older players stack the odds against them.

“It became clear to me mathematically that a lot of these guys are never going to know they made the Hall of Fame,” Dave Meador said. “Kenny Stabler never knew. Bob Hayes never knew.”

Although Meador died without being inducted at Canton, he did enjoy Eddie Meador Day at the Coliseum in 2018. In a video recorded by Meador’s daughter, Vicki, the Rams legend stood on the field he played on, waving to fans as they chanted his name.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.