- Share via

The weight has been unimaginable, a burden far bigger than a rushing defensive lineman, attacking with far more ferocity, and sometimes Matt Skura fights simply to stay on his feet.

While helping carry the Rams through this difficult season, the massive offensive lineman has struggled with the far more challenging task of carrying himself.

“Sometimes it gets to you,” he says tearfully. “The guilt.”

Last spring, Skura texted his father, Doug, with the news that he would be driving up from Charlotte, N.C., to Columbus, Ohio, to spend some time with his biggest fan.

“I wrote something like, ‘Hey Dad, I’m coming to Columbus, nothing going on, I just want to see you,’ ” Skura says.

Rams center Matt Skura is honoring his father, who died by suicide, while his teammates will highlight other groups on “My Cause My Cleats” Sunday.

Yet later that night, having been advised by his brother Brian that their father was not feeling well enough for visitors, Matt texted back that he would be delaying his trip.

“I texted him, ‘Hey Dad, I’m not going to come to Columbus after all, I think it’s good for you to take some time, I know you’ve got a lot of things going on …. but I love you and we’ll talk soon,’ ” Skura remembers.

The next day, Doug Skura, a respected 61-year-old orthopedic surgeon, took his life.

The shoes were beautiful, lyrical and startling.

For the NFL’s annual, “My Cause My Cleats” celebration earlier this season, Rams center Matt Skura arranged for his cleats to be painted in bright blue and yellow tones adorned with a clear message that many prefer to hide.

The shoes contained the phrase, “Out Of The Darkness,” — one of the themes of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

The cleats also contained the words, “Douglas Skura Memorial Fund.”

Anybody who saw them could combine the decorations and realize what they were really saying. Skura was courageously using his cleats to bare his soul, acknowledging publicly on a national stage the unspeakable tragedy that quietly results in nearly 50,000 deaths per year in America.

Nobody talks about suicide. Skura feels he must talk about it. Many people experience shame when a loved one dies by suicide. Skura wants to use his story to honor his father.

There are many emotions felt by survivors of suicide loss, and Skura feels a moral obligation to tackle them.

He wants to talk about unfounded guilt. He wants to address the unfair anger. He wants to talk about how it is OK to talk about all of it.

“I wanted to wear those cleats because I wanted to represent my dad,” Skura says. “I wanted to represent something I deeply care about. I went through something very tragic — myself and my family are still going through it — and I wanted to bring awareness about it and maybe help somebody else deal with it.”

Because Skura didn’t join the Rams until after the season started, few teammates knew his story. Because he didn’t crack the starting lineup until injuries created vacancies midway through the schedule, few fans even knew his name.

But in decorating the cleats, and then later enduring a 50-minute interview for this story while standing in a cluttered hallway at the Rams practice facility, Skura bravely chose to reveal his grief not only for public consumption but also for himself, for his family, for part of the healing process.

“I’ve learned that talking about it is kind of like a therapy in itself,” Skura says. “You’ve got to be able to talk about it, you can’t suppress it and hold it in, I was a little bit nervous about bringing this to light, but if this can help one person save another person’s life, then it’s been worth it.”

He talks about his ordeal with the same passion as he played through it this season, battling along a makeshift line, never using his misery as an excuse, embracing the game as a release.

“The football field has been my sanctuary,” he says.

He has been welcome in that sanctuary as a guy with a balky knee who can play through pain, both physical and mental. The effusive Sean McVay chose to describe Skura’s presence to reporters in just three simple phrases.

“His toughness, his competitiveness, the willingness to push through,” the coach said.

These are all traits Skura learned from his father, the giant Doug Skura, a 6-foot-6, 300-pound man with a brilliant mind and sentimental bones.

“My dad was a great father, a great husband, he was all about hard work, we learned so much from him,” Skura says.

Doug Skura was born in Coleman, Canada, a small town in the Canadian Rockies where his father worked in the coal mines. Doug used his brilliance and diligence to eventually become one of the most respected orthopedic surgeons in the Midwest, where he served patients in Pittsburgh and later Columbus.

But more than that, he was a devoted husband to Kristian for 36 years and a front-row-seat dad.

“He was such a great husband, such a great dad, involved in so much in our lives,” says Skura, who has two brothers.

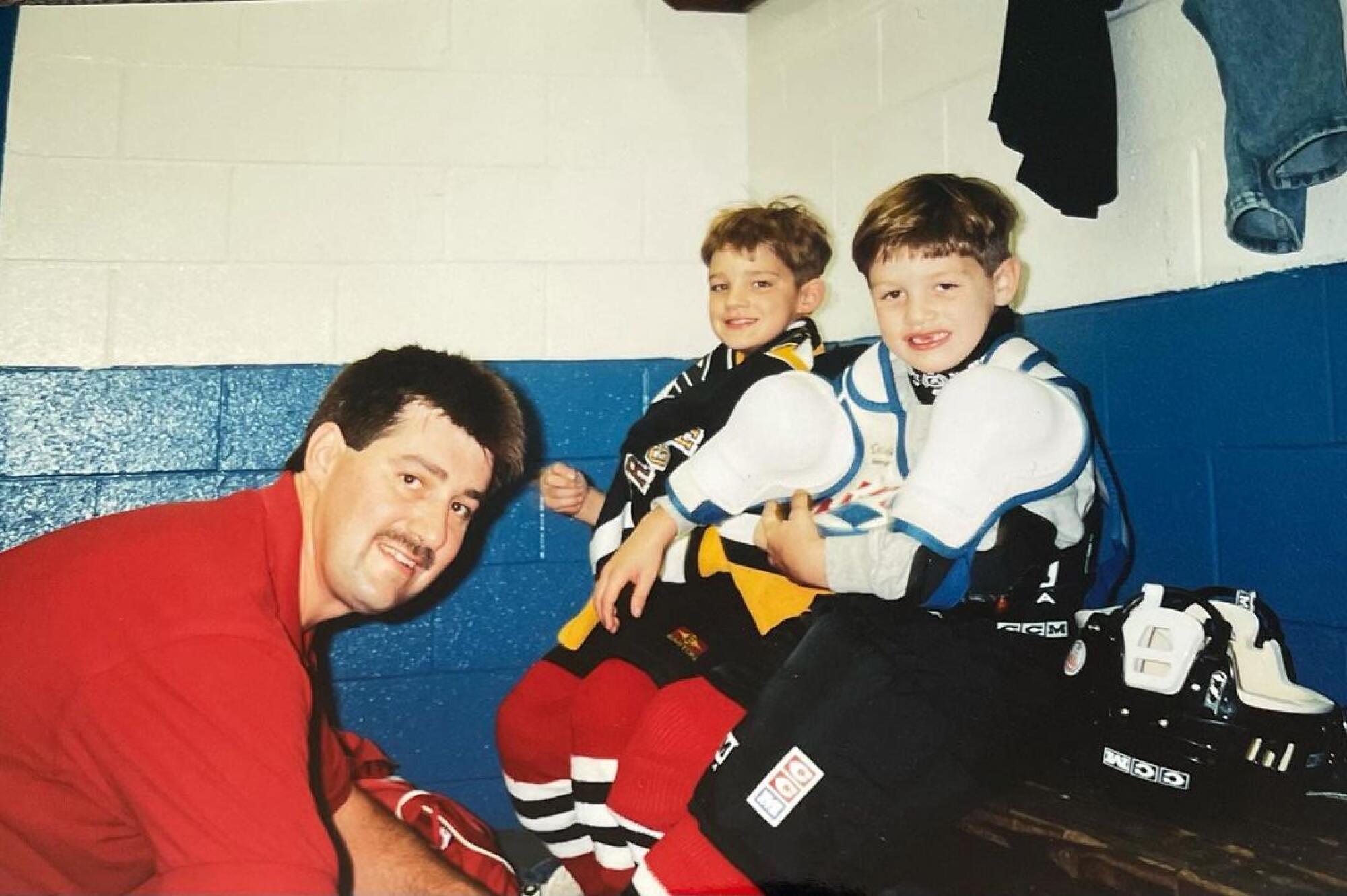

His father was their youth league baseball coach, their first hockey coach, their daily life coach, teaching by the way he juggled his enormously pressurized job with their enormously important childhood.

“We knew the sacrifices he made, we’d hear him get up at 5:30 in the morning and not see him come home till 9 at night … yet he still came to all of our games,” Skura says. “He was that kind of dad.”

He would take his boys swimming in Rocky Mountain rivers, he showed them how to ice fish, he taught them the meaning of work.

“Growing up he did everything with us,” says Skura’s older brother Brian, who followed in his father’s footsteps in becoming an orthopedic surgery resident. “He always made time to be there. He taught us life lessons.”

When Skura accepted a football scholarship at Duke, his father began flying Duke flags on his car and constantly wore a Duke windbreaker with his son’s number 62 on it — wore it everywhere, even at the hospital. When Skura began his career as an undrafted free agent with the Baltimore Ravens in 2016, his father not only wore a Ravens jersey but also once ventured into Cleveland’s infamous Dawg Pound cheering section to show it off.

“I’m like, ‘Dad, you’ve got to be careful!’ ” Skura remembers.

Doug Skura could never be shy about his affection for his sons. He saved every ticket stub to every game. He saved every DVD recording of every game with notations written on each disc such as, “Big block from Matt!”

As his middle son began growing into a 6-foot-3, 305-pound athlete, his father was so proud of his youthful strength, he sometimes called him, “Matt Truck.”

Later, as Skura bounced around from Baltimore to Miami to the New York Giants, one of the constants in his life was the texts from a man who never stopped cheering.

“Always, on Saturday night or Sunday morning, he would text me good luck,” Skura recalls. “Always.”

Skura thought those cheers would last forever. But then last winter, while shoveling snow, his father slipped and fell and suffered a concussion that seemed to send him spiraling.

Doug took early retirement from his beloved job at a local hospital and became depressed.

“My dad was overwhelmed things were changing,” Brian says. “He didn’t have his job, his kids had grown up and left the house, he felt like he lost his entire identity.”

The Skura family tried to convince him to seek help, but he resisted. As his depression grew, he promised he wouldn’t hurt himself, and they believed him.

“We tried so hard to get him help, my brothers and mom and I tried every day to keep his spirits lifted,” Matt says. “Yet still I wonder, what more could I have done?”

Experts say the guilt felt by a suicide loss survivor is common but unwarranted.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

“If someone is in the most physical pain of their lives and you would ask them for directions, they wouldn’t be able to help you because of their physical pain,” explains Louisa Rocque, executive director for the Greater Los Angeles & Central Coast American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “The same thing happens when that pain is in our brain. The person is so tunnel-visioned on that pain, it’s hard to see a way out of that darkness.”

When Skura received a phone call from his crying older brother while sitting with his wife at a Charlotte restaurant on that afternoon of March 10, their family’s road into that darkness was only just beginning.

“My brother was like, ‘Dad took his own life,’ ’’ Skura says. “You don’t even know how to process it. I just remember crying uncontrollably.”

Douglas Skura did not leave a note, only questions that the family will be asking forever.

“I did not see him making such a permanent decision,” Matt says. “I didn’t think he could do something like that to himself.”

These questions, accompanied by a range of emotions, are also not uncommon for suicide loss survivors.

“For most people, there isn’t a physical health reason for someone passing in this way, so there’s not that closure,” Rocque says. “There’s always a mix of feelings — guilt, anger, sadness — and I don’t really think that any of those ever go away. The journey of your loss is a forever journey.”

But, as Rocque notes, there is plenty of assistance available to help you through this journey.

“These days, I think way more about the all the good things my dad taught me … loving your kids, being a good dad, being there for your people, showing up.”

— Rams offensive lineman Matt Skura on his dad, Doug Skura

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, dial 988 or use the chat option 988lifeline.org. If you are looking for support groups or healing conversations, check the AFSP.org website.

Rocque says Skura has done a great public service by simply talking about it.

“There’s still a lot of stigma that surrounds suicide … the conversation is hard … people want to skirt around talking about it, it’s such a heavy topic to process,” she says. “But it is really, really helpful because the more that we talk about it, the more it normalizes the conversation and helps people digest a loss that’s unlike any other loss in life.”

As the longest football season of his life ends, Matt Skura vows to continue having this conversation, and hopes it can continue as a member of the Rams.

“This is one of the most healthy work environments I’ve ever been in,” he said. “McVay is a tremendous leader, also tremendous about mental health, the words you say to yourself, the words you say to each other. In the locker room, guys are really connected, the culture here has been amazing.”

A list of crisis hotlines, low-fee and sliding scale counseling, support groups, and mindfulness and meditation services

He still fights off feelings of anger and guilt, and he knows he’ll never have all the answers, but he forges forward, the cheers of his biggest fan eternally echoing through him.

“These days, I think way more about all the good things my dad taught me … loving your kids, being a good dad, being there for your people, showing up,” Skura says.

Which is exactly what he is doing now, amid this horrible tragedy, in this lost season, on inspirational cleats carrying a broken heart.

Matt Skura is showing up.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.