Brady Powers Offense That Doesn’t Quit

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — First to last, this was one of the closest and most entertaining of the many Super Bowls. During a long passing duel matching Tom Brady of the New England Patriots and Donovan McNabb of the Philadelphia Eagles, accompanied by a long defensive duel pairing two of the NFL’s best blitzing defenses, it was 0-0 after a quarter, 7-7 at the half, and 14-14 after three quarters.

All that time, though, the cleverly designed New England offense kept coming on. And at the outset of the fourth quarter, Brady led the Patriots to the 10 points that broke the game open. It was essentially over by the time the Eagles scored for the last time late Sunday night to make it a 24-21 victory for the Patriots and their coach, Bill Belichick.

Brady had come out passing at the start of the third quarter, throwing on seven of the nine plays of the touchdown drive that broke the halftime deadlock.

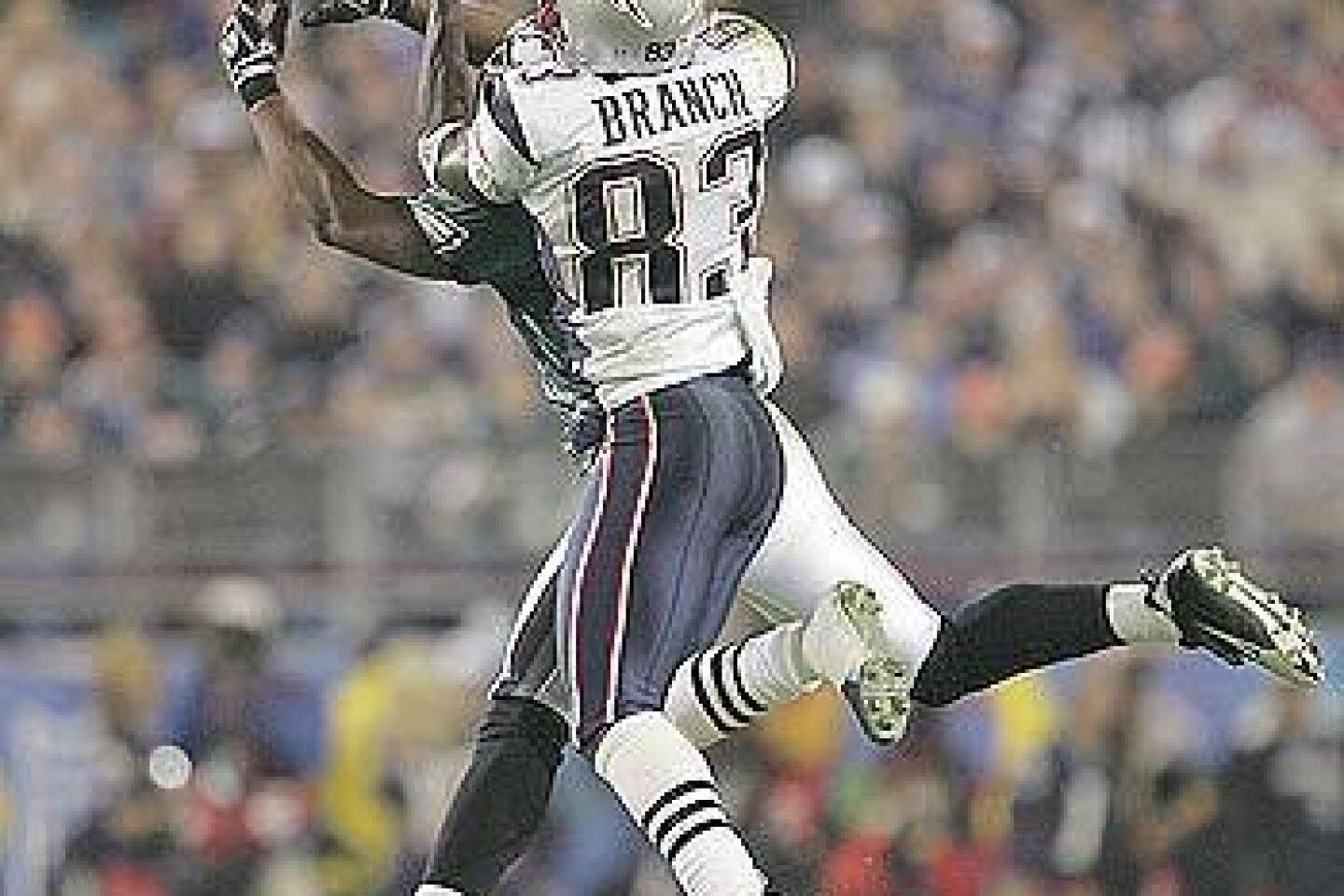

It seemed at that moment the Patriots had taken over, having finally solved the blitzing schemes of Eagle defensive coordinator Jim Johnson. Brady, passing most often to wide receiver Deion Branch, was basically unstoppable in the second half, when the Patriots punted only once until their lead was a safe 24-14 in the fourth quarter.

But that one punt was the signature play of a third-quarter interlude in which the Patriots stopped themselves.

After scoring the go-ahead touchdown at the start of the second half, they had quickly forced an Eagle punt that Troy Brown returned deep into Philadelphia territory. But Patriot safety Dexter Reid, who had been inserted for injured starter Eugene Wilson, was caught holding, and Brady was on his eight-yard-line instead of the opponent’s 38. And McNabb soon was back in business.

The mistake was one of many the Patriots made after a season in which they erred infrequently. Most of their errors — false starts and such foolish plays — came early in the game, when McNabb’s team scored first. That was good for McNabb and bad for his team, for it woke up the Patriots. They had sleepwalked through the first quarter, making only one first down, but thereafter they at least played well enough to win.

This was a game in which a member of the losing team, wide receiver Terrell Owens, earned the most-valuable-player trophy even though he didn’t get it.

A good two weeks before he should have played after breaking an ankle Christmas week, Owens caught McNabb’s passes everywhere on the field but deep.

Even in his present physical state, Owens was good enough to damage the Patriot defense as decoy and receiver. That led to an even game that the Eagles might have won if Owens had played it uninjured. In either case, that’s MVP stuff.

The compelling question today is how did Belichick do it? How did he and his team win three of the last four Super Bowls in a league with a hard, binding salary cap?

My answer after watching him this week is that he has reconceptualized the game in the same sense that Billy Beane of the Oakland Athletics has found a new way to play baseball.

Briefly, as Belichick’s scouts hunt for new Patriot players, they don’t search for the typically good football players that other teams seek. They look for Belichick players, athletes who have professional quality but who aren’t All-Pro.

Specifically, Belichick wants team players: those who are flexible, smart, coachable, motivated to enjoy hard work and psychologically mature. And if possible, they play more than one position. None of them is a star. None is a costly specialist. The Patriots, for example, don’t draft wide receivers in the first round.

Almost without exception, Patriot recruits are players no other club wants badly enough to pay for. But as midlevel draft choices, they do cost millions. In the salary-cap era, where do the Patriots find the millions? The key is that their pay is coming out of Brady’s pay. He has, so far, willingly accepted millions less than he’s worth to fund Patriot recruiting. He reasons that if there’s enough salary money for a championship cadre of teammates, he’ll get his back in endorsement money and the like.

Nobody knows how long Brady or Belichick will keep this strange procedure going, but it will last at least another year, long enough for the Patriots to win a third consecutive Super Bowl and fourth in five years, eclipsing Pittsburgh’s four in six years during the Terry Bradshaw era. The Patriots will get the record next Feb. 4, in Super Bowl XL, at Ford Field in Detroit.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.