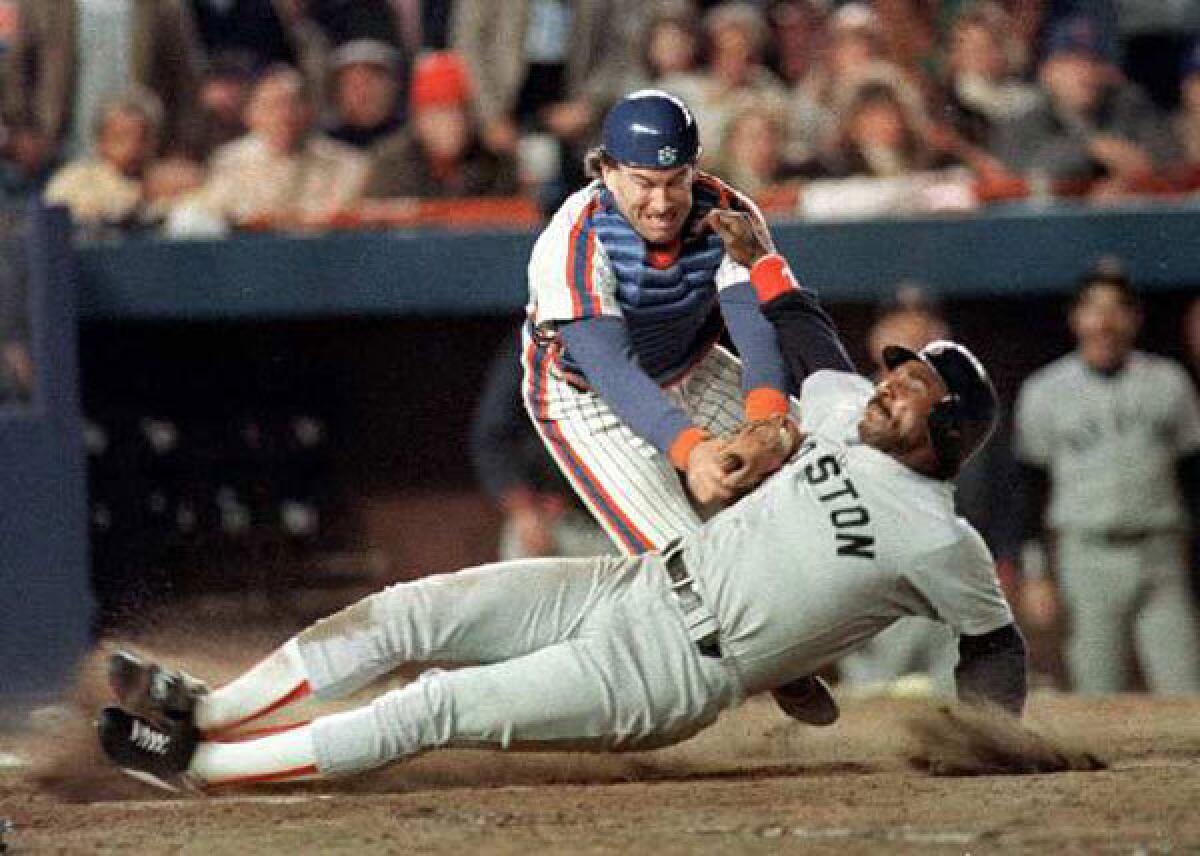

Gary Carter dies at 57; baseball Hall of Famer

Gary Carter, a Hall of Fame catcher from Fullerton who helped lift the New York Mets to a dramatic victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1986 World Series, died Thursday in Florida. He was 57 and had brain cancer.

Nicknamed âKidâ for his grit and youthful exuberance, Carter was an 11-time All-Star who hit .262 with 324 home runs and 1,225 runs batted in during 19 seasons playing for the Montreal Expos, Mets, San Francisco Giants and Dodgers.

His goal to become a major league manager unfulfilled, Carter was coaching at Palm Beach Atlantic University near his Florida home last May when he experienced headaches and forgetfulness and was diagnosed with brain cancer.

âNobody loved the game of baseball more than Gary Carter,â Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver said Thursday. âNobody enjoyed playing the game of baseball more than Gary Carter. He wore his heart on his sleeve every inning he played. For a catcher to play with that intensity in every game is special.â

Former Expos pitcher Steve Rogers, who is now a players union special assistant, played with Carter in Montreal. âGary and I grew up together in the game, and during our time with the Expos we were as close as brothers, if not closer,â Rogers said. âGary was a champion. He was a âgamerâ in every sense of the word â on the field and in life. He made everyone else around him better, and he made me a better pitcher.â

Angels Manager Mike Scioscia, who was Carterâs teammate with the Dodgers in 1991, remembered him as ânot only an incredible ballplayer but an incredible person.â

âI always admired him when I played against him,â Scioscia said, âand it was a pleasure to play with him.â

Born April 8, 1954, in Culver City, Carter was raised in Fullerton. His father, Jim, was an aircraft worker, and his older brother, Gordon, played two years in the Giantsâ minor league system.

Carter told Sport magazine that a turning point in his life was the death of his mother when he was 12. Inge Carter suffered from leukemia and died when she was 37.

âI took it very personally, very hard,â Carter said. âOne thing it did was turn me off God for a while and onto sports. I really feel everything good I did on a field was for my mother.â

Carter excelled on many athletic fields, collecting 11 varsity letters at Sunny Hills High School in Fullerton and earning more than 100 college scholarship offers in baseball, football and basketball.

Though a knee injury forced him to miss his senior football season at Sunny Hills, Carter, a quarterback, was set to attend UCLA on a football scholarship until the Expos selected him in the third round of the 1972 draft and signed him for $40,000.

Carter reached the big leagues two years later. In 10 years with the Expos, the 6-foot-2, 215-pounder with the dimpled chin, curly brown hair and ever-present smile hit .272, averaged 21 homers, 26 doubles and 80 RBIs a season and was a seven-time All-Star.

Carter was a rare player who would stand outside the park and talk to fans at length. In spring training, he set aside time to pose for pictures and sign autographs.

He was so accessible to and talkative with the media that once, according to Sports Illustrated, as a sportswriter approached Carter in the clubhouse, a teammate cried out, âGary, at least wait until the guy asks a question.â

A trade to the New York Mets before the 1985 season thrust Carter from the relative obscurity of small-market Montreal into the limelight of the nationâs biggest media market, where Carter was scrutinized like never before.

Some thought Carter went too far out of his way for good press. Some teammates, resentful of the many endorsements and speaking engagements Carter garnered, thought he hogged the spotlight.

âIt was jealousy more than anything else,â Carter told The Times in 1993. âThey felt this guy was too good to be true, but I was the same as a rookie as I was the last day I took my uniform off.â

The Mets made Carter baseballâs highest-paid player with a $2.07-million salary in 1986, and Carter delivered with a superb season in which he hit .255 with 24 homers and 105 RBIs and finished third in National League most valuable player voting.

After a slow start in the postseason that October â he had one hit in his first 21 at-bats (.048) in the NL championship series against Houston â Carter warmed at the plate.

His run-scoring single in the 12th inning of Game 5 led the Mets to a 3-2 victory over the Astros, and Carter had two more hits in New Yorkâs pennant-clinching, 7-6, 16-inning win in Game 6.

After the Boston Red Sox won the first two games of the World Series in New York, Carter had three RBIs in the Metsâ Game 3 win and smashed two home runs over Fenway Parkâs famed Green Monster in left field to help the Mets even the series in Game 4.

And in the famous 10th inning of Game 6 at Shea Stadium, with the Red Sox one strike away from the World Series title, it was Carterâs single that started the rally that ended when Mookie Wilson hit the game-winning and series-tying grounder through the legs of Boston first baseman Bill Buckner.

The Mets won Game 7 two nights later, and Carterâs picture was plastered across two pages of Sports Illustrated as he ran to the mound thrusting his arm in the air, a wild grin across his face. That was typical Carter enthusiasm.

Carter was a four-time All-Star in five years with the Mets, batting .249 with 89 homers and 349 RBIs. He went on to play one season (1990) in San Francisco and one (1991) for the Dodgers.

He closed his big league career where it began, playing in Montreal in 1992. A three-time Gold Glove Award winner, Carter finished with an NL-record 2,056 games caught and is one of only six catchers with more than 300 home runs and 1,000 RBIs.

Carterâs father died in 2003 at age 84, only 17 days after his son called to tell him he had been elected into baseballâs Hall of Fame.

In an interview with The Times before his induction, Carter was teary-eyed as he spoke of his father, who was always upbeat, who always reminded his sons the value of wearing a smile and treating people properly.

âI wanted to live his legacy, make my life a reflection of his,â Carter said.

In memory of his mother, Inge, Carter tried to be âthe best person I can be,â he said. âShe is like this bird on my shoulder. When it comes to the final judgment day, I want to see her again. I want to be reunited with her in heaven.â

Carter is survived by his wife of 37 years, Sandy, who was his high school sweetheart; daughters Christy Kearce and Kimmy Bloemers; son D.J.; and three grandchildren.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.