Book excerpt: The grassroots war over Dodger Stadium that captivated a nation

The construction of Walter OâMalleyâs shining, new stadium on a hill that began in 1959 is not just a baseball story, but also of three communities that were displaced to build a housing project, only to find themselves on an unexpected collision course with L.A.âs determined effort to become a big league city.

On May 7, 1959, Los Angeles turned its eyes back to Brooklyn. Despite on-field struggles and off-field challenges since moving West in â58, the Dodgers had been a success in Los Angeles. Playing in the Memorial Coliseum, they drew nearly twice as many fans as they had in their final year in Brooklyn and more than any Dodgers team since 1947, the year Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier.

It was a Thursday night, and nearly 100,000 fans filled the Coliseum to watch an exhibition between the Dodgers and the New York Yankees. Thousands more were turned away at the gates. The occasion was a fund-raiser for Roy Campanella, the former Dodgers catcher who had never gotten the chance to play in Los Angeles. In January 1958, a few months after the team announced its move, Campanella crashed his car on an icy road. He was paralyzed from the shoulders down.

In decades to come, when sports franchises moved, they would rebrand, rename themselves, and make a point to erase their pasts. But Campanella was a Dodger â period. The size of the crowd was a testament to the fact that Angelenos had embraced not just the team in its present state but also all of its history. Los Angeles is always rewriting its past in the hope that doing so might brighten its future. The Dodgers celebrate their Brooklyn achievements to this day.

The crowd outside nearly overwhelmed the gates of the Coliseum. A cavalry of motorcycle cops had to be called in to put things in order. But inside, it was all splendid baseball magic. Before the first pitch was thrown by Sandy Koufax, Campanella was honored with a tribute recounting the glories of his career. Then, during a short break between the fifth and sixth innings, the stadium lights were turned out, and the 93,000 people in attendance all struck matches simultaneously, lighting up the darkened stadium like a night sky brimming with stars. Vin Scully asked the fans listening at home to say a prayer for the catcher. It was surreal. In his autobiography, Campanella likened the gesture to watching the Coliseum transform into a massive birthday cake.

::

Three miles away, Abrana and Manuel ArĂ©chiga sat in their home. The couple were among the last holdouts in the community of Palo Verde â most of which had been cleared years before in the cityâs doomed effort to build an ambitious public housing project called Elysian Park Heights. Now the couple had become symbols of resistance to the cityâs choice to turn and sell the land to the Dodgers.

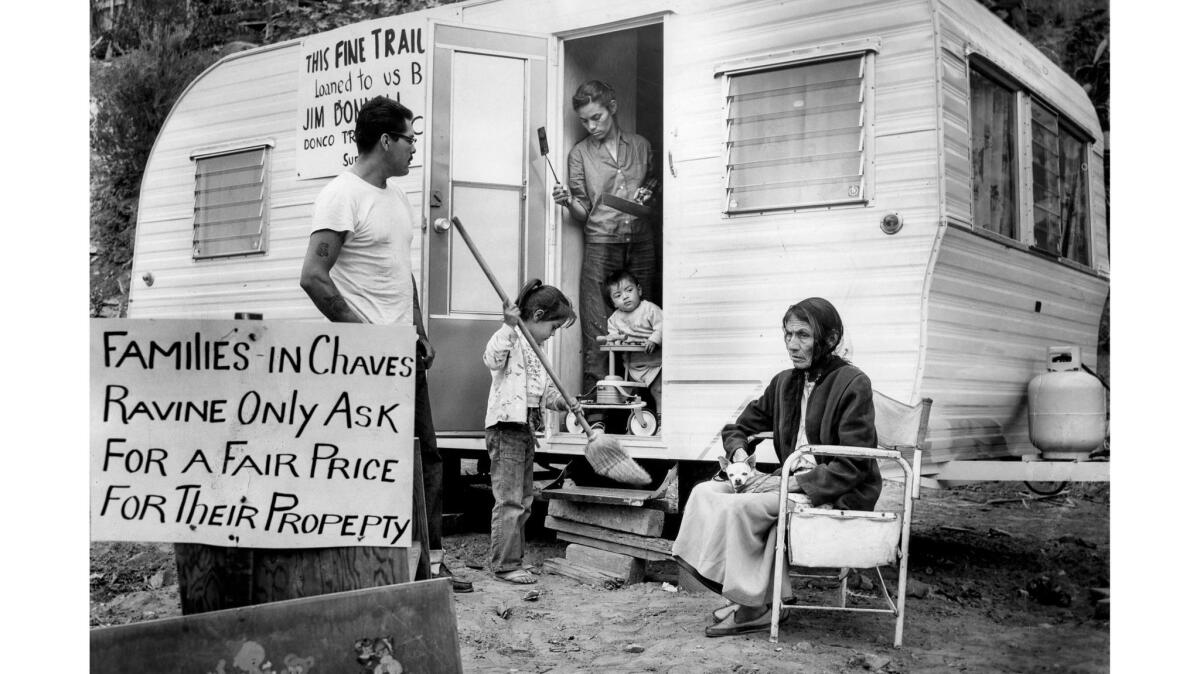

The following day would be May 8: the deadline for the ArĂ©chigasâ eviction order. It had been nearly 40 years since they moved to Palo Verde â one of three communities that make up what we now call âChavez Ravineâ and nearly a decade since that first letter from the housing authority had arrived in their mailbox on the corner of Malvina and Effie Street. That corner was different now. The houses around it were almost all gone, and the ones that remained looked like they were sinking into the dirt. The mailboxes were still there, but now they looked almost like headstones. Little monuments to past lives.

By now, Abrana and Manuel had become quite familiar with eviction orders, with sheriffâs deputies, and with empty threats. The city had spent nine years making it known to the family that the land they lived on was no longer theirs. And yet they were still there.

The towers of Elysian Park Heights had been as good as built, overlooking the downtown skyline â then they werenât.

There was supposed to be a zoo, a convention center, a cemetery.

There were lawsuits, one after another.

There was Walter OâMalley in his helicopter.

The city had tried everything to get them out. Once, Abrana reportedly turned her hose on a group of deputies. Another time, the city sent a dogcatcher to round up her Chihuahuas; he did not succeed. The city threatened to charge the ArĂ©chigas rent, but that plan never went anywhere because, in a typical catch-22, the city had already ruled the home a âslum dwellingâ as an excuse to evict them, so renting the home out would have effectively made the city government a slum lord.

In March 1959, a judge gave the ArĂ©chigas 30 daysâ notice. Then in April, councilman Ed Roybal had talked city officials into another 30. Roybal hoped that in the meantime the family and the city could reach some sort of settlement. The ArĂ©chigas were represented by attorney Phill Silver. The family wanted to see their case go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The council deliberated on a proposal to let them stay on Malvina until the Supreme Court had a chance to hear the case â or not hear it, if that was the courtâs will. This proposal was rejected.

Roybal understood that Dodger Stadium was inevitable. For as many wrenches as the Aréchigas and Silver could throw into its legal gears, the program was too big, the momentum too great. But Roybal also understood that the Aréchigas had a point and deserved to be heard.

Their grievance was reasonable, and it was minor. It came down to the difference between the $10,050 a judge had set as the property value of their lots seven years earlier and the $17,500 valuation that had been offered by a city appraiser and then overruled by the aforementioned judge. This was it: $7,450. What was $7,450 when set against the huge deal that the city had made with Walter OâMalley? Against the millions of taxpayer dollars and tens of millions more private dollars that would be spent on this project?

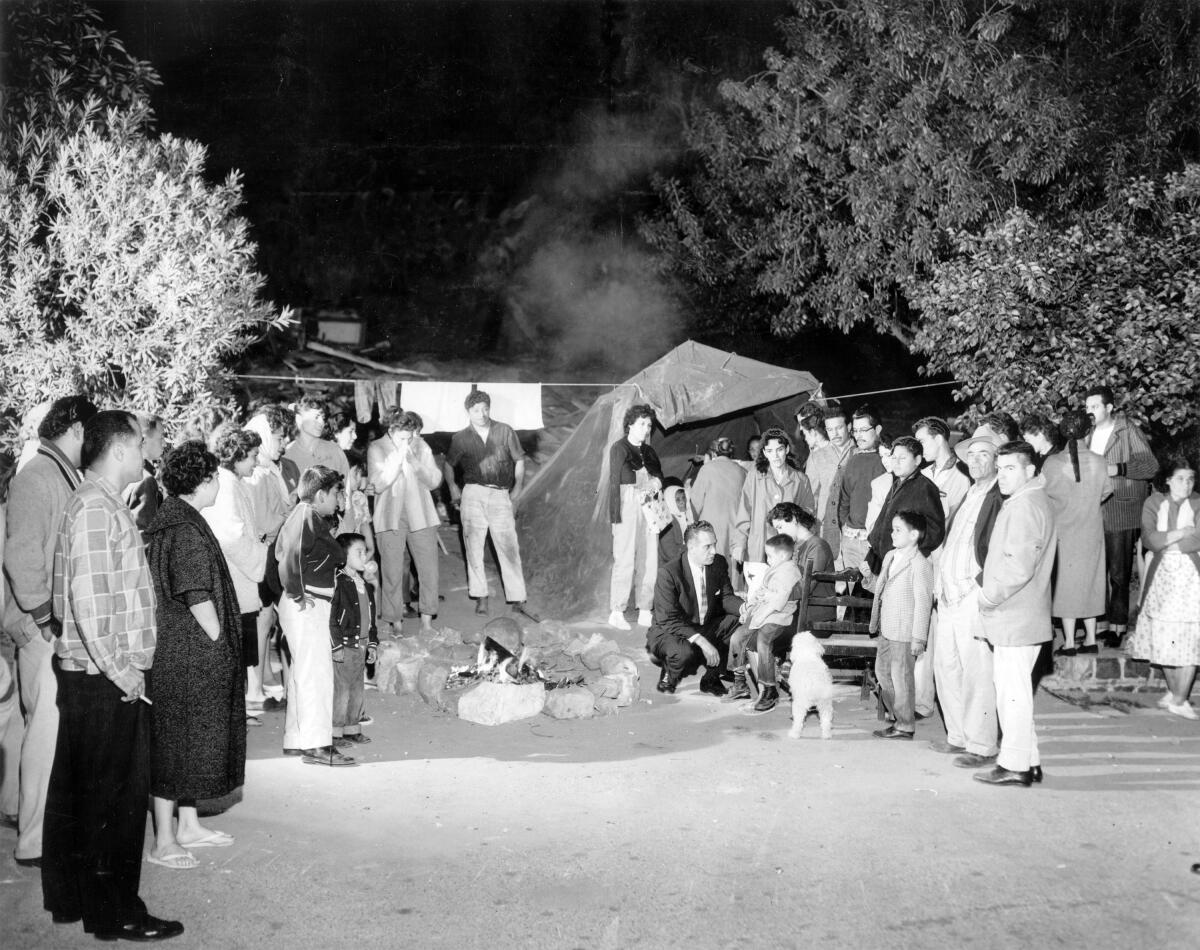

The surreal nature of the ArĂ©chigasâ plight was thrown into sharper relief by the fact that there remained a dozen or so property owners in the community who were not facing eviction that morning. These were the families who, years earlier, had filed an appeal in court that the ArĂ©chigas had, for some reason, missed out on, hence setting themselves on a separate legal path. These were families whose homes had not been officially condemned. And perhaps more importantly, these were families who had held out quietly, who had not picketed City Hall, and who had not previously spoken to the papers about the stadium deal.

Because of the ArĂ©chigasâ legal actions and public protests, they had become the faces of resistance in Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop, even if all they wanted was a fair deal.

::

Sometimes I think that Walter OâMalley himself should have simply cut a check. Had he known how poorly his partners in local government would handle things, perhaps he would have. At one point, the ArĂ©chigas essentially asked him for that check. On May 6, the day before the Campanella charity game, the Los Angeles Mirror-News published a letter from Manuel ArĂ©chiga. âI havenât anything against the Dodgers,â he wrote, âbut if they want my land let them pay a reasonable price for it, not take it away.â

But now here the Aréchigas were. Waiting. Watching the clock. On the night of May 7, while the city celebrated the Dodgers and Roy Campanella and lit their matches in tribute, Abrana and Manuel could only wonder what the morning would bring. Legally, they were at their end. It was likely, they knew, that men in uniforms would come to take them away from their home. It was likely, they knew, that politicians would strut and squawk. But they could not know how the following hours, days, and weeks would shape up. They just knew that something was coming.

This article has been adapted from Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between by Eric Nusbaum. Copyright © 2020. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. You can purchase the book here: https://www.amazon.com/Stealing-Home-Angeles-Dodgers-Between/dp/1541742214

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.