Apodaca: Teachers are starting to question the rewards of their profession

- Share via

It would be easy to assume that Patrick Gordon became a teacher because it’s in his blood. His army vet dad was a teacher, and his stepmother, stepsisters and stepfather also pursued careers in education.

Gordon, who lives in Huntington Beach and teaches Advanced Placement U.S. History at Gahr High School in Cerritos, is, by any measure, extremely good at his job. A natural, you might say.

Now in his 27th year of teaching, he is a long-serving department chair and faculty advisor for Gahr’s Model United Nations program. He has overseen substantial improvement in AP pass rates at the ethnically diverse school, where a majority of the students are economically disadvantaged. Some of his former students now have successful careers, and I’d wager that many consider Gordon an important influence behind their achievements.

Indeed, Gordon’s performance has been so impressive that in 2012 he was named a Jaime Escalante Teacher of the Year, a prestigious award named after the famous educator who inspired the film “Stand and Deliver.”

Despite all that, Gordon knows well that choosing to become a teacher — or to recommit to teaching year after year — is no easy decision. Unfortunately, that’s more true now than ever.

When speaking with Gordon recently, I was struck by how often this exceptional educator used the word “sad” to describe the state of teaching today. The disrespect, he said, is “depressing on a deep level.”

“I don’t need praise,” he emphasized. “I just don’t think that I’m being valued or that we are being valued anymore.”

(Full disclosure: Gordon’s wife Tracy is my longtime hairstylist and a dear friend.)

No doubt, teaching has always been a demanding job. But educators like Gordon once believed that, for the most part, the frustrations — as well as the lower pay compared with other professions requiring a similar level of education — were outweighed by the rewards.

Even at schools so underfunded that teachers routinely resorted to buying their own classroom supplies, many remained devoted to their careers because they loved what they did and believed in the positive impact they could have on young lives. Many took on second jobs so they could afford to keep teaching and still pay the bills.

But increasingly teachers are questioning whether it’s worth it anymore. Many report being worn out by years of top-down measures that have sapped their autonomy and sucked creativity from the learning process. Meanwhile, our fixation with standardized testing has drained more of the joy from teaching, and the growing politicization of education has teachers constantly on the defensive regarding what they say, how they plan their lessons and which books to assign.

Daily Pilot columnist Patrice Apodaca has begun to notice society’s common misconceptions about older people.

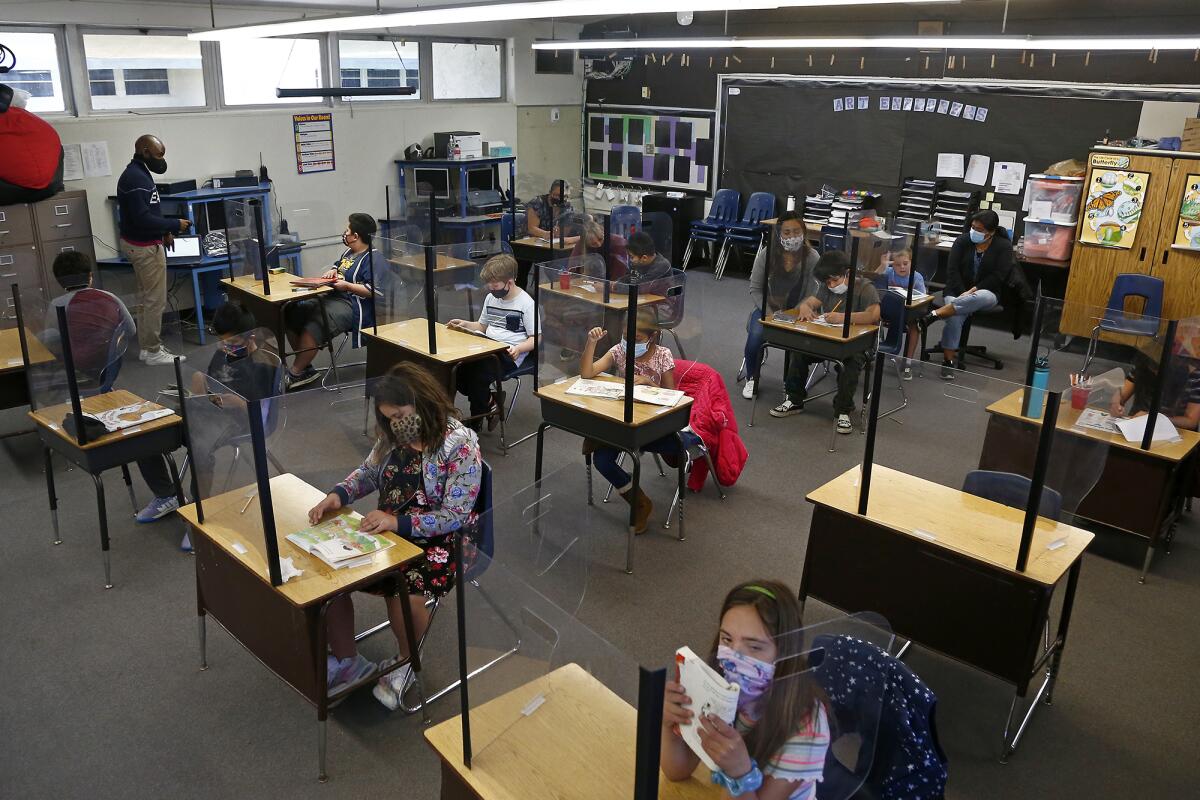

As bad as it’s been, when COVID-19 emerged the situation grew exponentially worse. Indeed, after an initial burst of public appreciation during the early days of the pandemic, the gratitude quickly evaporated and teachers went from rock stars to villains.

They were branded as selfish if they were reluctant to return to in-person teaching out of fear of infection, blamed for student learning losses after months of remote studies and expected to miraculously overcome the myriad of societal ills that plague our youth.

Add to that teachers’ daily worries about school safety and the now-standard training in how to respond during an active-shooter attack. And they’ve been on the receiving end of increasingly vitriolic and dangerous rhetoric aimed at stifling any classroom discussion that touches on racism or LGBTQ issues.

It should hardly come as a surprise that many teachers are now fed up.

Across the nation, concerns are mounting over potentially catastrophic teacher shortages. Some districts report hundreds, even thousands of vacancies; the National Education Assn. estimates that U.S. schools are currently in need of another 300,000 teachers and staff.

Some observers downplay the crisis. They note that teacher shortages aren’t new and that some districts have had no problems attracting and retaining personnel. There’s no comprehensive national data, so a complete picture remains elusive.

But we can’t ignore the fact that many campuses — often those that serve the most distressed communities — are losing teachers at alarming rates and can’t find enough replacements to fill the gaps.

The problem is so severe in some areas that certain districts have resorted to desperate measures — lessening requirements for entry-level teachers, boosting reliance on long-term subs, hiring students with incomplete training, increasing the burden on remaining teachers and even shortening workweeks to four days.

Veteran teachers like Gordon know that the deflating environment exacts a heavy toll.

“Some people can’t wait to get out, and they haven’t been there 30 years,” he said. “They’ve been there three.”

Many won’t even get that far. There are indications that young people are increasingly giving teaching a hard pass.

Gordon’s own daughter could be one of them. Now a college freshman, she has been discouraged from considering a future career in teaching by some family members — the same family with a proud heritage in education.

Their warnings should speak volumes about how badly we’ve lost our way.

Teaching is arguably the most important job, but you’d never know it by our contemptible treatment of this honorable profession. That’s not merely sad. It’s tragic.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.