Column: With artificial intelligence on the rise, humans should reconsider the way we think about our own

Intelligence: We all think we know it when we see it.

But do we really understand that elusive quality?

It’s clear that our ideas about intelligence have evolved over time as the skills deemed necessary for survival and success have changed. Just think about the way kids roll their eyes when their parents have a hard time understanding technology. Those young folks instinctively grasp what to us seems foreign and hopelessly confounding.

So now, as we anticipate the emergence of artificial intelligence in virtually every aspect of our lives, we have to ask ourselves: What will this development mean for human intelligence?

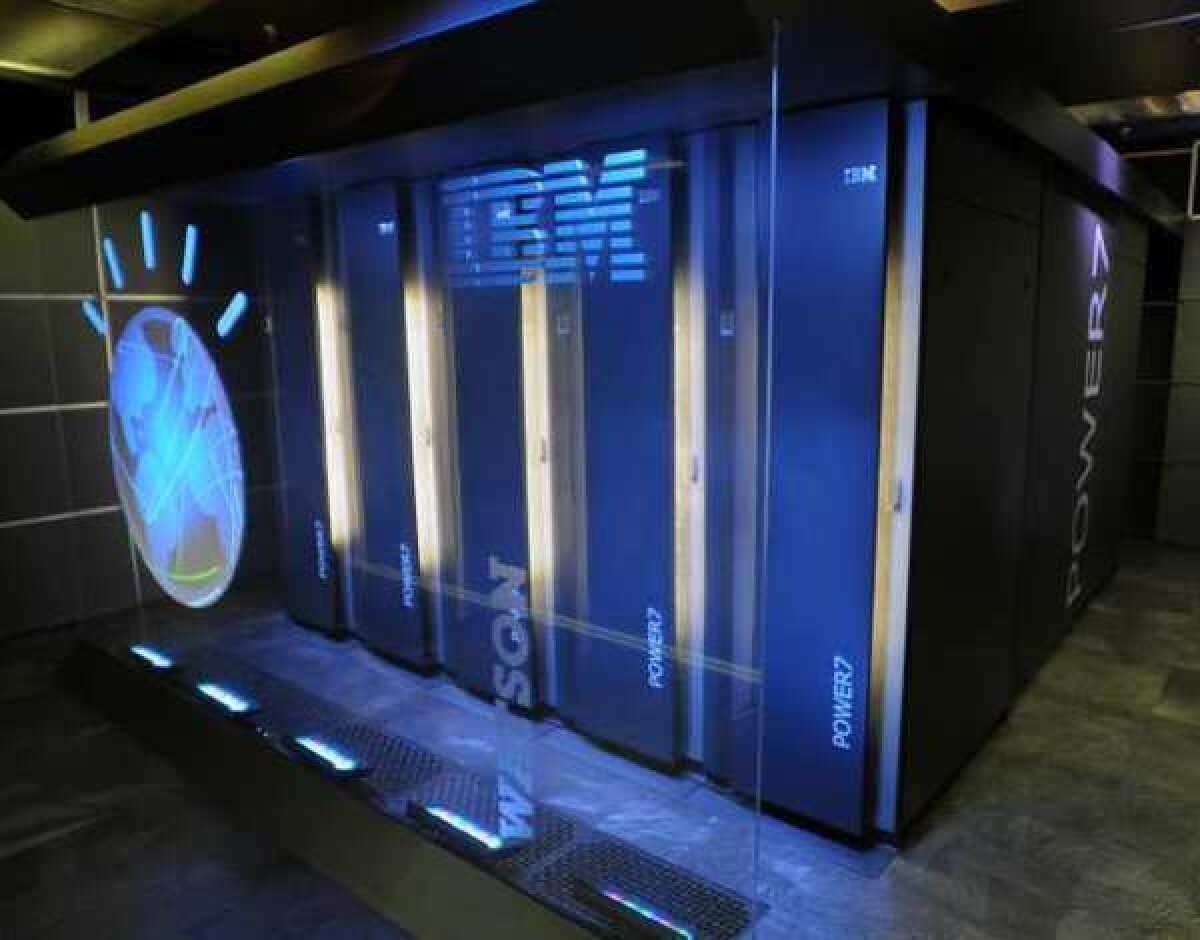

IBM’s Watson computer has already shown us that sophisticated machines can process, store and recall information faster and better than people. How can we prepare for a world in which computers are, in many ways, smarter than we are?

I posed such questions to a local expert, Pierre Baldi, who has devoted his professional career to matters of intelligence — both human and artificial.

Baldi has a resume as impressive as it is long. Raised in Italy and France, he earned a doctorate in mathematics at Caltech. He is now a distinguished professor of computer science at UC Irvine, director of UCI’s Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics and associate director of the university’s Center for Machine Learning and Intelligent Systems.

I could go on listing his accomplishments, but you get the idea. Baldi knows a lot about intelligence, and he’s no slouch in the IQ department himself. Yet, in a delicious bit of irony, he admitted that he’s not all that fond of efforts to define intelligence.

“I don’t think there is a good, precise definition of intelligence,” he said. “It’s probably not a good idea to try to define it.”

Indeed, the idea of intelligence, as well as other complex concepts such as memory and consciousness, “are all very vague, and were developed at a time when we knew little about how the brain works,” Baldi explained.

We know a lot more now about how the brain functions and we are developing machines that essentially mimic human cognition. This is what’s known as artificial intelligence — an emerging field that is currently in an embryonic phase, but which elicits both hope and fear for the future.

Some people have compared AI’s potential to transform society to the harnessing and widespread application of electricity.

Baldi draws another analogy, comparing this stage of AI to the early days of flight, when pioneering inventors like the Wright brothers took inspiration from birds. As our understanding of aerodynamics deepened, we evolved from clunky designs to increasingly advanced, sophisticated and diverse aerial vehicles.

So it will be with AI, Baldi believes. Like the human brain, computers will interact with the world in an adaptive, intelligent way. They won’t merely process information; they will have the ability to learn.

In such a world, “probably a word like ‘intelligence’ will become obsolete,” he said. Or at least, the value of human intelligence will be seen in a different light.

Such predictions might make us uneasy, but consider that, in some ways, we’re already there. The boundary between human and machine continues to thin. Many of us have artificial parts in our bodies and cell phones have become akin to indispensable appendages.

“You can’t take one from a teenager,” Baldi said. “They can’t live without it.”

Despite AI’s potential to replace workers, Baldi believes the human element will continue to be valued in many professions — at least for awhile.

He cited the example of a radiologist. A computer can be programmed to interpret and analyze medical images, probably better than a doctor. But, in what Baldi refers to as the second phase of AI, he expects that patients will still want to interact with their doctors.

It’s when we get into the next phase that things get a bit murkier. Many jobs will simply disappear.

This has enormous implications not only for industry and society, but also for education.

Are we adequately preparing students for a world that will require higher-order critical, creative and innovative thinking, in which emotional intelligence — the ability to handle interpersonal relationships judiciously and empathetically — will be crucial to professional success?

I’d argue that we are not.

We continue to focus far too much of our educational system on rote learning and memorization. Rather than fostering creativity, risk-taking, adaptability and collaboration, we narrowly measure students’ intellect and reward them based on standardized test scores.

This must change.

Schools must move away from the drill-and-test model to one in which students are engaged in their own learning and a culture of “productive failure” and problem solving is embraced. Instead of telling kids what to learn, we should teach them how to learn and, perhaps most critically, we must encourage them to think.

And maybe we should also stop considering intelligence to be a static, tightly defined quality that you either have or you don’t. After all, we’re not machines.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.