Losing ‘Sunny,’ Part 3: After nearly 20 years of grief for family and friends, a cold case gets warmer

- Share via

In the months after her daughter, Adrienne, was killed, Sandy Sudweeks started attending monthly Parents of Murdered Children meetings.

Those days were a blur. She didn’t take much time off work. She saw a therapist who said her first task was to learn to deal with the grief and reconstruct her personality. The concept at first struck Sandy as odd.

The therapist told her that personalities, especially in developed countries, are based on an expectation that life is stable and safe.

“Now you know that’s not true,” the therapist said.

Sandy read books about grieving and did writing exercises to help her remember Adrienne, whom she called “Sunny.”

The first Mother’s Day without Adrienne was especially difficult. She sent a letter to the Los Angeles Times for a Mother’s Wishes column on May 5, 1997. It had been less than three months since her 26-year-old daughter was raped and strangled to death in Costa Mesa.

Sandy’s request to people who read the column wasn’t something that could be found at a store. Instead, she sought memories.

Do you have pictures of her? Is her voice on your answering machine? Do you have any letters or poems she’s written? Do you have any silly stories or recollections of her?

“Since I can’t have my daughter on Mother’s Day, what I would cherish the most is memories of her,” Sandy wrote.

In the Parents of Murdered Children meetings, Sandy was overwhelmed by the families’ grief, but she found talking about her daughter cathartic.

“I saw people in the group who years later were totally destroyed,” she said. “Their whole lives revolved around their loss.”

She wasn’t going to be that way.

“I’ve lost her, but I’m not going to lose the rest of my life,” she said. “I’m going to do all the things and live the life that she can’t.”

So she did. She continued pursuing their shared passion for travel, leaving a bit of Adrienne’s ashes wherever she touched down.

The impact of Adrienne’s killing is like a drop of water that creates a ripple spreading to each person who knew her.

For Peter Vukmirovic Stevens, it’s proof that when a person dies, the courses of other people’s lives are altered.

Stevens, a composer and artist now living in Paris, met Adrienne at Saguaro High School in Scottsdale, Ariz. She was a junior, he a freshman. They became fast friends, bonding over a shared appreciation for punk shows and art. She was like a sister to him.

After Adrienne moved to California, the two kept in touch through frequent calls and letters. He last spoke with Adrienne about 10 days before her body was found Feb. 23, 1997.

“You’re with somebody, and all of a sudden they’re absent, and they’re absent through violent means,” he said. “How do you get through that? It’s a blow you cannot recover from.”

Her death had a profound effect on his world view. He said he finds himself peering into the dark corners of his mind, anticipating tragedy that may never strike. More than once, he arrived home to a silent apartment and wondered whether his girlfriend had been hurt or killed. He couldn’t suppress the morbid depths of his imagination.

More difficult is the absence of justice for his friend, and the possibility that there never will be.

“Time does not heal all the wounds,” he said.

Richard Johnson, Adrienne’s boyfriend, started seeing a therapist in December 1997. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress syndrome, exacerbated by his belief that he wasn’t being provided information about the investigation of Adrienne’s slaying, according to a letter from his therapist that was submitted to Orange County Superior Court in 1998 after Johnson was arrested on suspicion of placing annoying phone calls to Costa Mesa police.

Johnson often had called detectives to inquire about the case, but in February 1998, nearly a year after Adrienne’s death, the situation with police came to a head.

He asked for details about their investigation and whether they had looked at the drug dealers who often were present outside the apartment where Adrienne was killed. Then-Det. Frank Rudisill told him he wasn’t going to discuss the case — after all, Johnson wasn’t married to Adrienne. He was told not to call back.

“I’ll call you whenever I want, and you can’t stop me,” Johnson said, according to the Police Department’s written account of the incident.

He hung up and called then-Chief Dave Snowden and left this message:

“I just wanted to call and say I don’t think you guys are doing a very good job and … I’d like my property back, if that’s possible, and I did this little interview with Channel 2 that you’re gonna love where I called you guys a bunch of doughnut-eating, ticket-writing losers who couldn’t catch a murderer even though there’s one right next to them.”

Two months later, Johnson was arrested and charged with three misdemeanor counts of making obscene phone calls to the department. He pleaded not guilty, and the charges were later dismissed.

In a 1998 Daily Pilot article about Adrienne’s case, police said Johnson had been investigated and not eliminated as a suspect.

Looking back, Johnson contends police arrested him in retaliation for questioning their aptitude.

“They just wanted me to go away,” he said.

Police publicly announcing that he had not been eliminated as a suspect further enraged Johnson. He upped the ante, passing out fliers criticizing the investigation and holding vigils for Adrienne.

“They knew I didn’t do it from the very beginning,” he said. “They just wanted it to be me so bad.”

Costa Mesa police said department policy prevents them from commenting about the crime for this series.

The case lay dormant for years, but in April 2016, the Police Department took advantage of funding for cold cases and assigned Det. Jose Morales to review Adrienne’s file.

Detectives had reviewed the case in 2009, but no new information emerged.

DNA of a potential suspect was collected from semen found on Adrienne’s body in 1997 and was twice submitted to the Combined DNA Index System, a computer system that stores DNA profiles created by federal, state and local crime laboratories. It never returned a match.

Morales pored over every report generated in the investigation.

The Orange County Crime Lab examined fingernail scrapings from Adrienne, a bloodied pillowcase and breast and anal swabs to try to determine whether more than one person was involved in the crime.

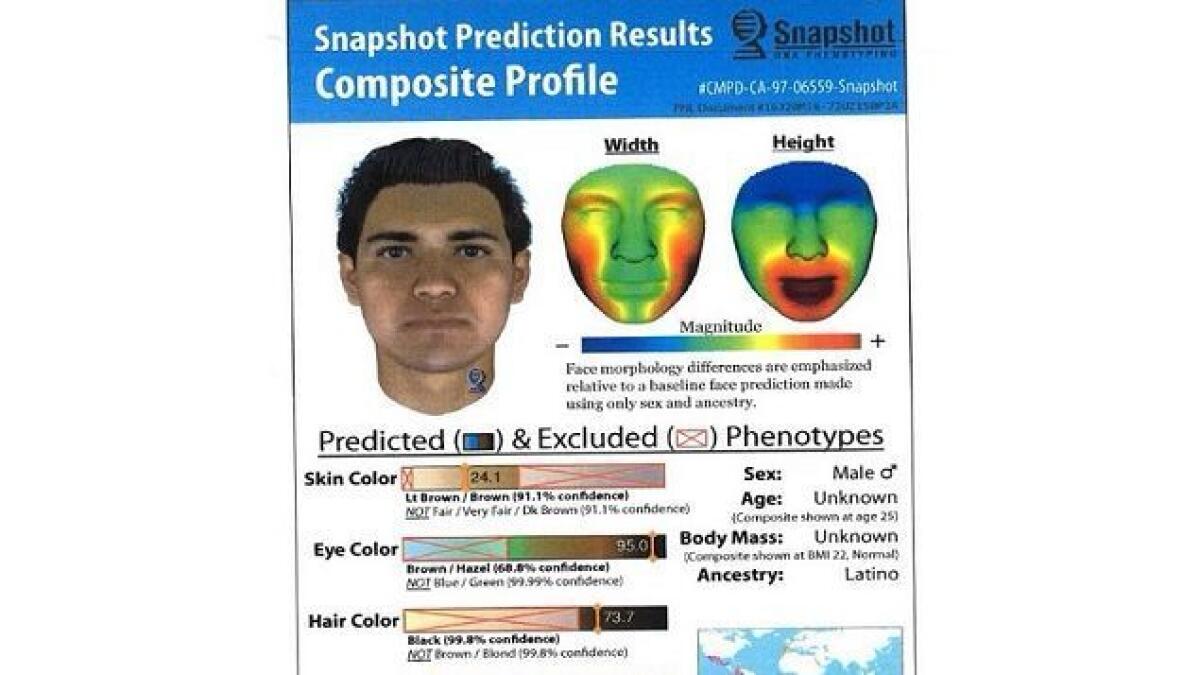

During a conversation with the county district attorney’s office, Morales learned that Parabon NanoLabs, a medical laboratory based in Virginia, could provide a snapshot profile of a possible suspect using physical evidence. The process uses DNA to calculate the person’s facial features, skin, eye and hair color, freckles, gender and ancestry.

Two weeks later, analysis of the samples described a male likely of Hispanic ancestry with brown eyes, dark brown hair and no freckles. The lab provided a composite of how the man might have looked at age 25.

In November 2016, detectives asked the county crime lab to rerun fingerprints lifted from Adrienne’s apartment during the initial investigation. The first fingerprint, from the doorknob inside the northwest bedroom, registered a hit.

Finally, police had a name: Felipe Vianney Hernandez Tellez.

Detectives pulled Tellez’s booking photo from a 2000 spousal abuse arrest in Santa Ana.

The resemblance between the photo and the profile generated by Parabon NanoLabs stunned the detectives.

Tellez was born in Mexico City in 1973 and came to the United States under a visitor’s visa when he was 19. He lived in Costa Mesa and Santa Ana.

He was arrested in December 1995 after gaining access to a home in Newport Beach through a second-story window. He was later convicted of felony burglary, according to court records.

In May 2000, he was arrested after his wife told police that he pulled her hair, kicked her and tried to strangle her. He was later convicted of misdemeanor counts of battery and inflicting corporal injury on a spouse, according to court records.

It isn’t clear why Tellez’s fingerprints, collected in relation to those earlier cases, didn’t register in connection to Adrienne’s case until 2016.

Once he became a suspect in her slaying, police staked out two possible addresses for Tellez but couldn’t find him.

On Nov. 15, 2016, Costa Mesa police Sgt. Stephanie Selinske and investigator Lily Martinez posed as potential clients seeking a painter and approached Tellez’s brother at a job site in Irvine. He told them his father and older brother had died but his mother, sister and younger brother lived in Mexico.

The next day, Morales and Costa Mesa Det. Jason Chamness posed as college representatives visiting Santa Ana High School and met over lunch with Tellez’s then-16-year-old son.

The boy washed down bites with apple juice and chocolate milk while he shared his ideas about college.

He said he lived with his mother and hadn’t seen his father in 10 years.

After the teen returned to class, the detectives snatched his juice carton from the trash and drove it to the county crime lab for analysis.

Two days later, the lab said the DNA analysis indicated a high likelihood that the teen was related to the person who left DNA on Adrienne’s body.

This is the third of four parts. In Part 4, detectives interview Tellez and authorities begin pursuing his extradition to the United States. But the ordeal is far from over for Adrienne’s family and friends.

Twitter: @HannahFryTCN

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.