Westminster council takes steps to recognize historic civil rights case

The landmark Mendez v. Westminster school desegregation case was the forerunner of nationwide integration of U.S. public schools, but until now, it’s never been honored in Westminster.

“I am pretty shocked that Westminster still hasn’t created a memorial for [the Mendez family],” Obed Silva, an English professor at Cypress College told the City Council on April 26.

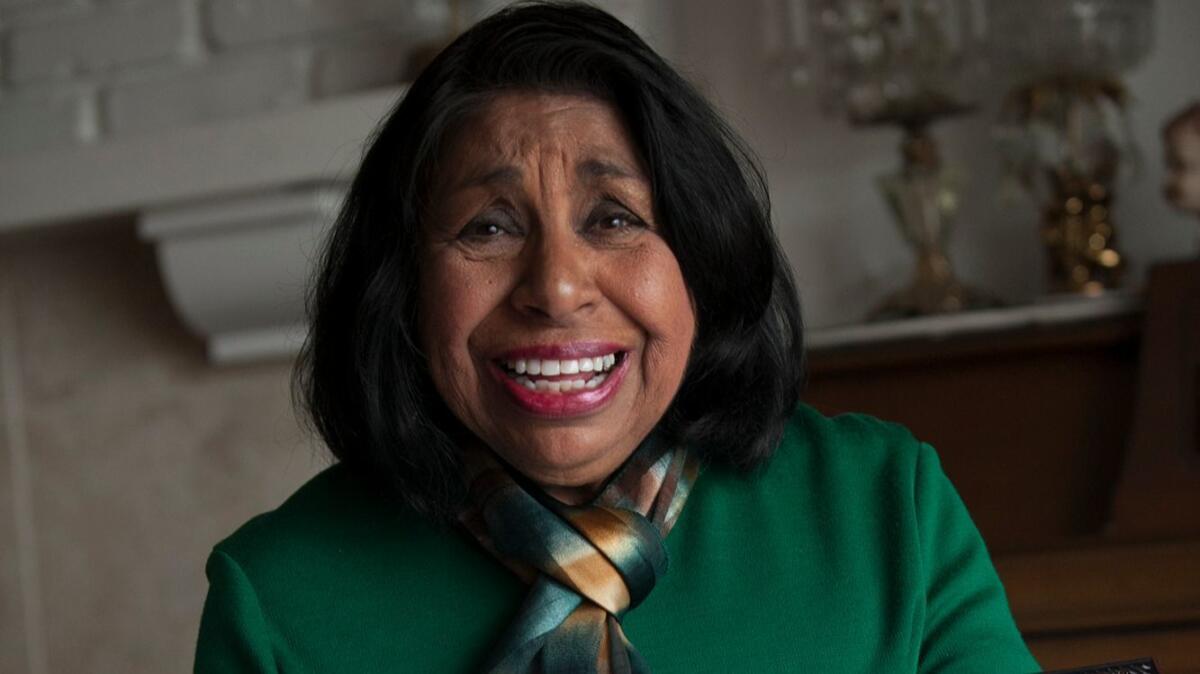

Sylvia Mendez, who was 9 when her parents sued the Westminster School District, told council members it was time they recognized the city’s civil rights history.

“There is no public place of recognition in Westminster. It is largely unknown here,” said Mendez, who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011 by then-President Barack Obama.

Council members voted unanimously to approve Councilman Sergio Contreras’ proposal to apply for state cap-and-trade funds to create a historic bike trail on Hoover Street, which passes through the elementary school site that was central to the 1946 lawsuit.

The two-mile bike trail along an unused railroad right-of-way would begin on Hoover at Bolsa Avenue, end at Garden Grove Boulevard and include educational information about the case and possibly commemorative public art. It’s part of a city plan to create bike trail and green space for residents.

The city has already spent $16,000 out of its general fund cleaning up the trail and another $2.3 million in municipal lighting and park dedication funds on bike trail improvements.

“I was really surprised that the past City Council or Westminster schools did not come up with any ideas to honor the family properly,” Mayor Tri Ta said. “I think this is the time, a good start.”

The case began when five Mexican-American fathers challenged the practice of barring Mexican-American children from attending public schools with whites. The suit specifically cited the El Modena, Garden Grove, Westminster and Santa Ana school districts.

Mendez v. Westminster began as a state case but school districts appealed the court’s decision, which required them to integrate. The districts lost on appeal to the federal courts.

It was the first time a federal court declared the practice of school segregation unjust and set the stage for Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision that ended school segregation nationwide.

Following the federal decision, the state Legislature passed, and Gov. Earl Warren, a Republican, signed a bill outlawing segregation in all California schools. Warren was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1953 and, a year later, led the court’s majority in the Brown v. Board of Education decision that required integration of the nation’s schools.

‘No Dogs and No Mexicans Allowed’

It was a time when restaurants posted signs like “No Dogs and No Mexicans Allowed.”

In the fall of 1944, Gonzalo and Felicita Mendez tried to enroll their three children at the Westminster Main Street School. But the children instead were assigned to Hoover Elementary, a school for Mexican children only, according to the National Archives website.

Four other families joined the Mendez family in suing four local school districts. During the trial, one Orange County superintendent said “Mexicans are inferior in personal hygiene, ability, and in their economic outlook” in justifying the district’s segregation policy, according to the National Archives website.

“[My mother] was born on Baker Street in Placentia and restricted to go only to the Baker School where she was hit if she ever spoke Spanish,” Therese Mosqueda-Ponce, a counselor at Cypress College, told the Westminster City Council last week.

Mosqueda-Ponce was one of several educators who spoke before the council who said many of her students were unaware of Mendez v. Westminster.

Silva said while the city is known for and celebrates its large Vietnamese community, it has not given the same attention to a defining moment in the city’s – and the nation’s — history.

Silva noted the Santa Ana School District has named an intermediate school after the Mendez family, and the Los Angeles Unified School District has dedicated a high school in Boyle Heights.

Westminster has a more recent history of discrimination against Latinos. Resident Mark Lawrence, who ran unsuccessfully for City Council in 2016, pointed to a 2011 lawsuit brought by three Latino Westminster police officers who alleged they were denied promotions because of their ethnicity. A federal jury awarded the officers a $3.5 million judgment.

Resident Lupe Fisher said the case isn’t just about fighting for equality for Mexican children.

“It’s way overdue, and we owe it to our children,” Fisher said. “I don’t mean our Latino children, our Mexican-American children … history is for everyone.”

Without Mendez v. Westminster, Fisher told the City Council’s three Vietnamese and one Latino members, they wouldn’t be sitting where they are today.

“We have a diverse City Council. If it wasn’t for this case, most of you wouldn’t be here – it would be Margie and maybe Mr. Jones,” Fisher said, referring to Councilwoman Margie Rice and City Attorney Richard Jones.

This story was reported by Voice of OC, a nonprofit investigative newsroom, as part of a publishing agreement with TimesOC. Contact Thy Vo at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @thyanhvo.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.