New federal program hopes to prevent homelessness in young adults aging out of the foster care system

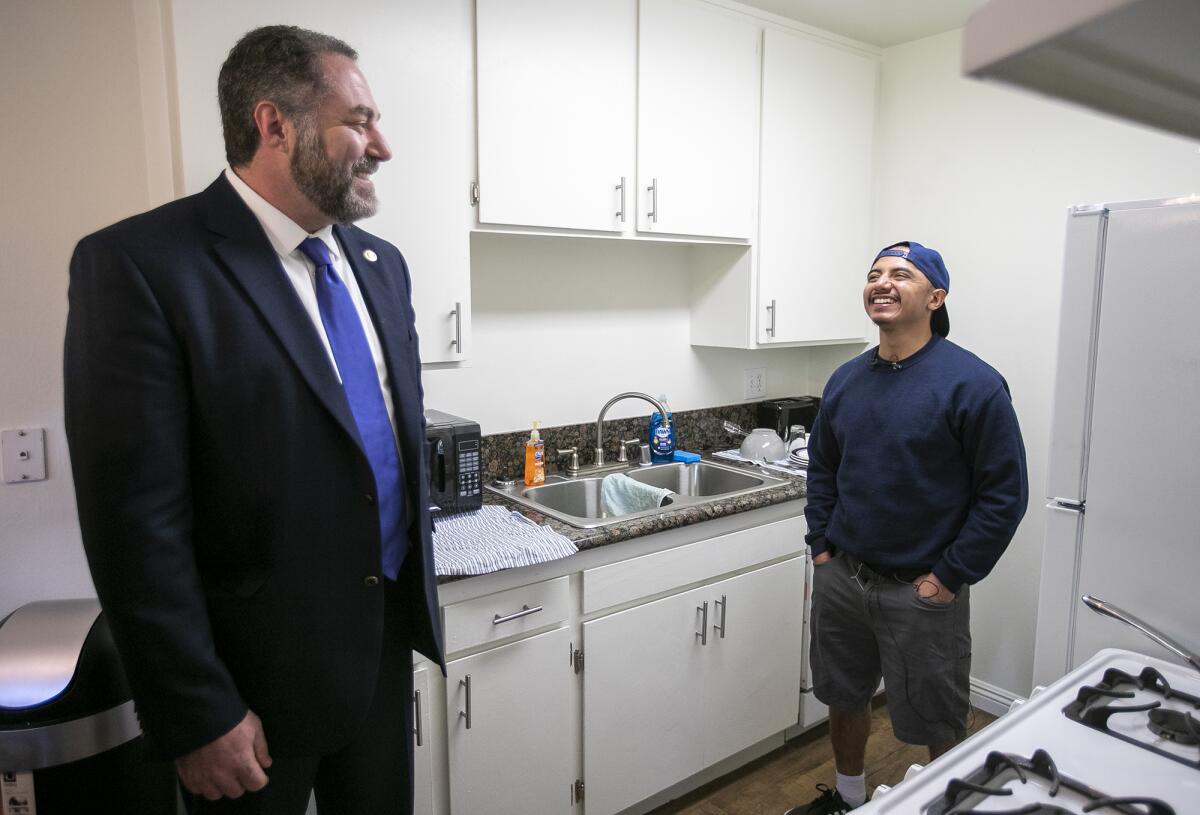

Giggling with excitement, Christian, a 22-year-old former foster youth, showed off his new apartment in Tustin on Thursday.

“I couldn’t believe it was my place,” Christian said. “It’s my place, my decision. I don’t have to listen to other people’s rules.

This Christmas, he has his own home for the first time since he was 9 years old.

The Orange County native has been homeless for the last three years, since aging out of the foster care system at 18. Shortly after, Christian suffered a traumatic brain injury when he was hit by a car and was in a coma for six months.

After waking up, the young man slept at a Santa Ana homeless shelter called the Link for nearly a year.

He asked we not use his last name out of concern his background will harm job prospects.

Christian moved into a one-bedroom apartment last week thanks to a new federal program that aims to prevent foster youth from 18 to 24 years old from falling into homelessness.

The Santa Ana Housing Authority, in partnership with the Orange County Social Services Agency, secured vouchers that provide rent support for Christian and 14 other former foster kids under the Foster Youth to Independence program, an initiative of the Housing and Urban Development department.

His favorite hobby in his new home is drawing in adult coloring books. He loves that he can use his private balcony to securely store his prized position, a BMX bike.

Senior Social Services Supervisor Lourdes Chavez said she thought Christian was younger than he really was when she first met him at the Link. Then she realized his brain injury impacted his speech.

Despite his challenges, Christian is planning to get a job, earn his GED, and obtain a driver’s license, she said.

Christopher Patterson, regional administrator for the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, said he sees himself in the 22-year-old man.

“I wanted to start crying,” Patterson said. “Kids who have been through the system don’t trust most people and why should they?”

Patterson was bounced around to temporary foster families in his hometown of Spokane, Wash. until he was adopted at 5 years old. Then he was put back in the system at 12 until he was taken in by his final foster parents, who also ended up fostering his brother.

He managed 10 group homes for foster kids in the Pacific Northwest before HUD Secretary Ben Carson was appointed to oversee the Department’s work in California, Arizona, Nevada, Hawaii, and U.S. Pacific territories.

The Foster Youth to Independence program was created, introduced, and passed by Congress within four months, demonstrating bipartisanship in a time of deep partisan divide in national politics, Patterson said.

“It’s a monumental lift that’s never been done before, and that’s why it’s so important to do this right,” he said.

The HUD program is providing 24,000 vouchers to young adults across the nation who left the foster care system, mostly within the last year. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that more than 23,000 young people age out of foster care each year.

The National Center for Housing and Child Welfare estimates about 25% of these young people experience homelessness within four years of leaving the foster system and an even higher percentage are precariously housed.

For the first time in his life, Christian has the stability to do everything from cooking meals to applying for Supplemental Security Income from the Social Security Administration.

“That’s a big deal,” Patterson said. “It’s somewhere he can lock the door and feel safe.”

In November, the Santa Ana Housing Authority and OC Social Services hosted 25 former foster kids for a briefing on the new HUD voucher program. Some of the attendees were apprehensive about the proposal, said Becks Heyhoe, director of United to End Homelessness, who was invited to observe the event.

“You could see how the room changed as these youths realized that there were people there to help them find a home,” she said.

Under the umbrella of Orange County United Way, United to End Homelessness has raised $148,000 to help pay for security deposits, household appliances, cooking utensils, cleaning supplies, and insurance fees that will turn apartments into homes for Christian and 24 other former foster youths and their children.

“I think today shows the collective impact of public and private partnerships when we all work together and bring our piece to the table,” Heyhoe said.

To learn how you can help end homelessness in Orange County visit unitedtoendhomelessness.org.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.