- Share via

The COVID-19 pandemic is receding fast into our collective memory. But the virus that caused it lives on in our sewers, our backyards and maybe even curled up in a sunny spot on the living room floor.

The coronavirus that prompted more than 750 million infections in humans and nearly 7 million deaths has also spread to creatures great and small. Lions and tigers have caught it. So have pet dogs and cats. Scientists have even found SARS-CoV-2 in armadillos, anteaters, otters and manatees, among others.

At least 32 animal species in 39 countries have had confirmed coronavirus infections. For the most part, the animals do not become very ill. Still, some are capable of transmitting the virus to other members of their species, just like the asymptomatic humans who became “silent spreaders.”

The coronavirus’ ability to infect so many different animals, and to spread within some of those populations, is worrying news: It means there’s virtually no chance the world will ever be rid of this particularly destructive coronavirus, scientists said.

And that’s not even the worst of it: As long as SARS-CoV-2 is spreading in animals, the virus has the opportunity to acquire new mutations that could make it more dangerous to people. If circumstances align, the result would be Pandemic 2.0.

The Path from Pandemic

This is the sixth in an occasional series of stories about the transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic and how life in the U.S. will be changed in its wake.

Scientists aren’t saying this scenario is likely. But it’s not so far-fetched.

In fact, this sequence of events — a virus that jumps from animals to humans and capitalizes on gaps in our immunity — is just how most “zoonotic” outbreaks begin. It remains the most likely explanation for how a coronavirus circulating in horseshoe bats in China came to infect humans in the first place.

Two new studies build on evidence that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 jumped to humans in a Wuhan market, and did so twice.

When a virus that has made humans sick recedes but continues to circulate within a population of animals, those creatures become what scientists call a reservoir. Within a herd, flock, clowder, pack or pod, it quietly preserves its potential to reinfect humans and rekindle outbreaks.

The virus may adapt to its animal host by flipping a few genetic switches. The result could be a pathogen that the human immune system no longer recognizes, or that causes more severe illness than the last time around.

To do real damage, animal reservoirs must be in regular contact with people. They may be livestock on farms, family pets or wildlife neighbors who leave their saliva or droppings in our yards or on hiking trails.

Whether any particular species can be said to serve as a reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 is a hotly debated question among scientists right now, said Dr. Angela Bosco-Lauth, a Colorado State University veterinarian who studies zoonotic diseases.

So far, no single species has checked off all the boxes, “which isn’t to say we should call it over and stop looking,” she said. “It’s hard to predict. But we know that if we don’t look, we won’t find it.”

Virologists, immunologists and wildlife scientists have shown that a few species have some of the capabilities necessary to become a reservoir.

One animal population — white-tailed deer — continues to pass SARS-CoV-2 amongst itself. Another — American mink — can not only be infected but reinfected with the pandemic virus, raising the prospect that it could live on indefinitely. In both cases, studies have shown that the coronavirus is actively mutating to adapt to a new host species.

There’s also the documented phenomenon of farmed mink in Denmark and pet shop hamsters in Hong Kong passing the virus back to humans.

The number of wildlife species that might harbor the virus is substantial. A group led by UC Davis geneticists found that, in addition to humans, 46 species of mammals have receptors on their cells that suggest they are vulnerable to infection with SARS-CoV-2.

The World Health Organization is so concerned that animals will become sanctuaries for the pandemic virus that it called on all member countries to conduct active surveillance of their wildlife. Cervids — the family of animals that includes deer — exist in various forms all over the world, and are considered prime candidates for providing a coronavirus reservoir. Other leading contenders are apes and “Old World primates” — macaques, baboons, gorillas and chimpanzees — whose genetic similarity to humans makes them susceptible to infection, and whose exposure to humans around the world is substantial.

The only species in which scientists have documented continued spread of the pandemic virus is white-tailed deer, the most abundant large mammal in North America and a denizen of backyards and wooded areas across much of the country. In places in the U.S. where the animals are densely concentrated, at least a third are believed to have been infected with the virus at some point during the pandemic. (Mule deer, which are more common across the West, have been shown to sustain and transmit coronavirus infections as well.)

California wildlife officials have confirmed the state’s first case of COVID-19 in a wild animal, detected in a mule deer killed in 2021 in El Dorado County.

A study published in January found that white-tail deer continued to harbor the Alpha, Delta and Gamma coronavirus variants long after they had stopped circulating in the U.S. population. The fact that deer populations could keep these variants alive and flourishing even after they had left humans is seen as a strong sign that deer might well serve as reservoirs for the pandemic virus.

Deer harvested by hunters across New York state yielded other surprises: As the virus passed through herds, it took on new mutations, including several in the spike protein that it uses as a key to enter and infect cells.

Jeff Bowman, a wildlife scientist for the province of Ontario, Canada, is the senior author of research that documented the discovery in wild deer not only of a virus with a record 76 mutations, but also a “spillback” transmission of another strain from a deer to a human. Still, he acknowledged that whether deer have become a reservoir for the SARS-CoV-2 virus “remains an open question at the moment.”

In human populations, the pandemic virus flipped genetic switches often, mostly in ways that were neutral or that made it less threatening. But as it settles in among new host populations, it may well evolve in different ways.

“When they get in, they’re not subtle,” said Washington State University molecular virologist Michael Letko, who has studied how members of the coronavirus family adapt to new hosts. “They’re evading immune responses and trying to survive.”

That puts enormous pressure on the virus’ latching mechanism — its spike protein — to embrace any mutations that help it get the job done. Whether those mutations also make the virus more virulent is “just the luck of the draw,” Letko said. “It’s the unknown that makes it kind of tricky.”

The Canadian government has kept tabs on the virus in its deer and other wildlife populations by piggybacking its surveillance on an existing program to detect chronic wasting disease and rabies. Hunters and trappers have been enlisted to bring their harvests to researchers for testing, and wildlife crews collect animal carcasses in woods and scrape up roadkill to round out the picture.

In the United States, the Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services has been sampling white-tailed deer in the wild since November 2021 and is expected to release new findings soon.

So far, there’s no evidence that the mutations detected after the virus’ sojourn among white-tailed deer in New York made it more dangerous in any way. But the effect of any changes might not become evident until an infected deer passed it on to a human.

In order to move through a world where the coronavirus is endemic, we need a reliable way to assess our individual level of immunity. Here’s how we can.

Finlay Maguire, an infectious disease genomic epidemiologist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, is one of the Canadian researchers monitoring the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in white-tailed deer there, and he has not detected worrying genetic changes — so far.

“We haven’t seen signs of strong selective pressure that would make [the virus] better suited to humans,” he said.

There’s other reassuring research as well: Researchers have found no reason to believe birds can catch the coronavirus. That’s important because birds flock, fly and migrate, and are raised as livestock as well. All those attributes make them exceptionally prolific spreaders of pathogens capable of infecting humans. (Case in point: influenza.)

Researchers have also ruled out the ability of pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, alpacas, rabbits and horses to sustain a SARS-CoV-2 infection — a relief considering that these livestock animals are in routine contact with human caregivers.

Bosco-Lauth of Colorado State said the animals that live closest to humans — dogs and cats — can become infected but are unlikely to serve as effective reservoirs for the virus. Dogs may lick our faces and cats will gladly sneeze in them. But neither has shown it is capable of efficiently transmitting the virus, either to their human housemates or others of their species.

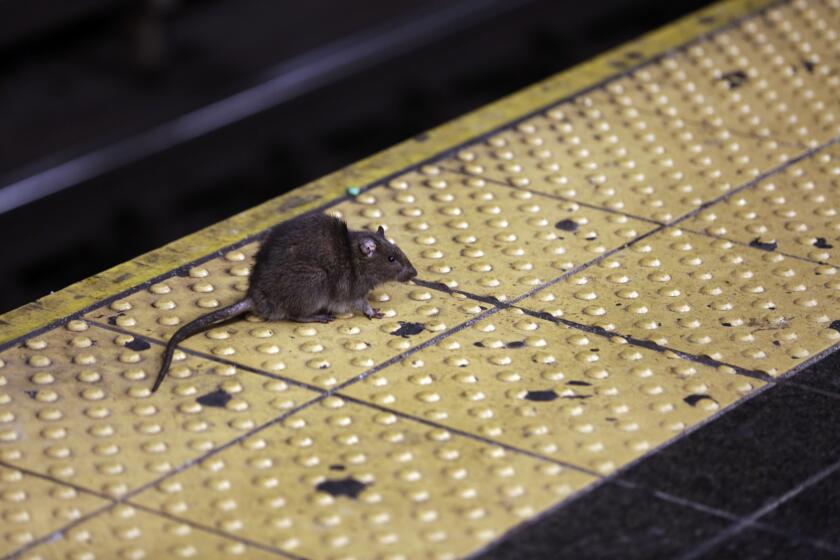

She added that researchers have yet to find a species that, when infected, excretes much live virus in its feces. Much has been made of the discovery of infected rats living near New York sewers. But if they can’t transmit the pathogen through their droppings, rats and other wildlife aren’t likely to infect humans very efficiently.

Rats living in New York City’s sewer system can catch the virus that causes COVID-19. Could they incubate new variants and spread them to people?

“There aren’t a whole lot of wildlife species I’m really worried about,” Bosco-Lauth said.

There’s one species, however, that continues to raise concerns among scientists: Homo sapiens.

“COVID-19 is still circulating in the human population, and people are getting infected and reinfected repeatedly,” said Graham Belsham, a Copenhagen University virologist who studied the spread of the pandemic virus in farmed mink in Denmark. “The virus hasn’t gone away, so people are probably the biggest threat to other people for years to come.”