No-cost preventive health services are now in jeopardy. Here’s what you need to know

- Share via

When a federal judge in Texas declared unconstitutional a popular part of the Affordable Care Act that ensures no-cost preventive care for certain services, such as screening exams for conditions such as diabetes, hepatitis, and certain cancers, it left a lot of people with a lot of questions.

On the face of it, the March 30 decision could affect ACA and job-based insurance plans nationwide and a host of medical services now free for patients.

What does this mean, really, for people with insurance? Policy and legal experts say there are some unanswered questions and a whole lot of nuances.

First, some background. The case, the latest legal challenge to the ACA, was brought by several individuals and an employer in Texas who argued the law’s requirement of free preventive care is unconstitutional, and also contended that requiring coverage of HIV prevention treatment can violate employers’ religious rights.

U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor agreed with some of their arguments, declaring unconstitutional one way the recommended tests are chosen, and agreeing that requiring employers to offer preexposure prophylaxis treatment for HIV, known as PrEP, violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. But O’Connor disagreed on other points that could have eliminated no-pay coverage for such things as contraceptives and vaccines.

Trump-appointed judges in Texas are stripping all Americans of their rights to healthcare and safety. At last, the Biden administration is pushing back.

Despite the ruling, nothing much is likely to change for enrollees in the short term, as insurers and employers are expected to be reluctant or even unable to immediately begin charging copayments or deductibles for the affected preventive care.

But as the case makes its way through the court system — both the Department of Justice and the plaintiffs have filed notices that they would appeal — here are four things to keep in mind.

A lot remains uncertain

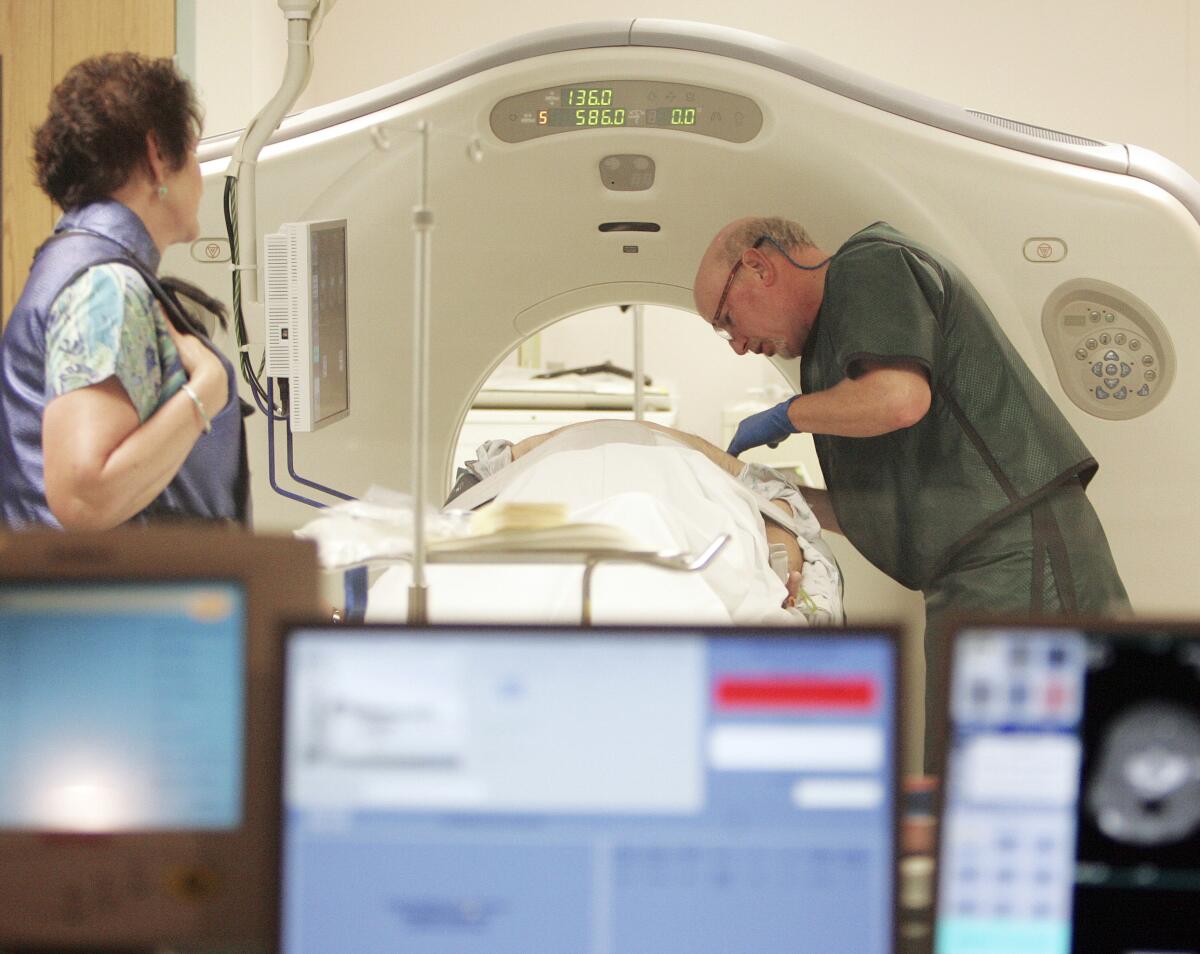

Because of the ACA, most insured people currently get preventive care that includes screening tests like mammograms and colonoscopies — along with other exams, such as checks for bone thinning in older women, depression in adults, or obesity in children — without being charged a copay or money toward a deductible. There’s a long list of qualifying services, including all those that get a top “A” or “B” recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, or USPSTF, an independent group of volunteer experts.

But O’Connor, of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, said members of that volunteer task force, who are appointed by the director of a federal agency, are “‘officers’ of the United States” and therefore need to be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Because they are not, he ruled that the use of their recommendations to set free preventive services under the ACA is unconstitutional.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Who are these people?

Here’s where things get confusing, because not all of the more than 50 task force recommendations would necessarily be affected if the ruling stands.

Some policy experts said certain services would remain free of copayments or other cost sharing for patients, partly because certain tests or treatments are also recommended under guidelines from other federal agencies and are therefore not affected by the ruling.

The federal Health Resources and Services Administration, for example, sets preventive care guidelines for a host of women’s health issues, including mammograms and contraception, although there is an exemption for religious employers. Additionally, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory committee recommends certain vaccines for children and adults. Further, cost sharing might not apply to some services because many experts expect the ruling will not impact tests or treatment recommendations made before 2010, the year the ACA went into effect.

“The idea is that when Congress passed the ACA, it adopted all the recommendations from the USPSTF prior to 2010, but anything since then the judge says is not constitutional,” said Timothy Jost, law professor emeritus at Washington and Lee University School of Law who closely follows the ACA.

What is certain

One problem, though, is most of the recommendations have been revised, part of the task force’s ongoing work to update recommendations as new scientific evidence arises.

A recent addition, for example, made in 2021, was to recommend that adults ages 45 to 49 get screened for colorectal cancer. Prior to that, the screening was aimed mainly at adults 50 and older.

One possible effect of the judge’s ruling, if it’s not overturned on appeal, is that people ages 45 to 49 might no longer be guaranteed no-copay colon cancer screenings.

U.S. doctors should regularly screen all adults under 65 for anxiety, an influential health guidelines group proposed Tuesday.

But the changes could be broader.

That’s because it isn’t clear how the ruling would affect recommendations that have been revised since 2010. For instance, would any revision or update made by the task force since 2010 make the entire recommendation subject to the ruling, Jost asked, or would the ruling apply only to the change made, such as the expansion of the age for colon cancer screening?

“Is everything the USPSTF touched since 2010 now unconstitutional?” asked Jost.

There may be only two pre-2010 recommendations that are unchanged since then, and both involve tests done during pregnancy to see whether the blood of mothers and babies is compatible, said Dr. A. Mark Fendrick, director of the Center for Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan.

New or updated recommendations include: a 2019 recommendation that PrEP be offered to people at high risk of getting HIV, a 2021 update for annual lung cancer scans for certain current or former smokers, and screening for hepatitis C in adults ages 18 to 79, updated in 2020.

Your coverage and your geography matter

Each insurer and self-insured employer will decide whether to reinstate copayments or other cost sharing for these services. Even if they do, it may take time for them to go into effect, especially given that policies are now in the middle of a plan year, making them contractually hard to change.

“It will depend on your employer and what they want to do, and depend on whether you have a collective bargaining agreement and a whole lot of other variables,” said Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law and policy at George Washington University.

That type of varying coverage was “exactly what the ACA was designed to get away from, in order to make this more uniform for all of us,” Rosenbaum added.

Even with the ruling, at least 15 states have laws requiring coverage of preventive services without cost sharing, according to an analysis by researchers at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

But state rules apply only to ACA plans and job-based plans offered by employers who buy coverage from an insurer. Most large employers — and a growing number of smaller ones — self-insure and are not subject to state coverage rules.

What happens next

Congress could resolve the matter with a simple fix to the ACA, said Fendrick of the University of Michigan. “Give the task force recommendations approval by the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services and it’s done,” he said.

Still, even though the preventive services coverage is very popular with consumers, the politics of changing the ACA are challenging, especially in a sharply divided Congress.

In the meantime, the case will go through the appeals process, and a final resolution could take months or even years.

The Department of Justice will seek to overturn the ruling, while plaintiffs will likely seek to broaden it, by challenging the parts of the judge’s ruling that went against them. Specifically, the individuals and employer who brought the case wanted the ruling also to cover recommendations made by other agencies, including the set of women’s health recommendations that include contraceptives.

“Everything as far as we are concerned is in play,” Rosenbaum said.