A COVID-19 vaccine is now available for young kids. Should they get it?

As any kid will tell you, grown-ups like to make things complicated. And they rarely miss a chance to argue about stuff.

Case in point: the COVID-19 vaccination for children ages 5 to 11.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization for kid-sized doses of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention followed up by recommending broad use of the vaccine among the nationâs 28 million elementary-school-age children.

The action had been recommended by two panels of independent experts who advise the FDA and CDC on vaccines. Now shots are going into little arms.

When it comes to adults and older kids, groups like this have almost always said everyone should get vaccinated. But this time was different: Several members of the FDA advisory panel made clear that they do not think the vaccination should be given to as many young children as possible, at least right now.

The CDCâs Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices did not share those reservations, especially in light of data suggesting the vaccine was more than 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 in 5- to 11-year-olds.

âBased on our expertise and the information that we have, weâre all very enthusiastic,â said committee member Dr. Beth Bell, a professor of global health at the University of Washington.

Hereâs a closer look at the debate over the vaccination of young children.

Why all the drama?

You might be wondering why thereâs even a question about whether to vaccinate kids against COVID-19.

The danger of the disease seems clear: At least 94 children ages 5 to 11 have died of COVID-19 since the pandemic began, and 8,300 have become so sick they needed to be hospitalized.

Even some who had only mild symptoms went on to develop MIS-C, a condition in which the immune system goes haywire and starts attacking perfectly healthy parts of the body. By early October, 5,217 kids had come down with MIS-C, including 2,034 between 6 and 11. Between 1% and 2% of them died.

Thereâs also the possibility they could develop âlong COVID.â In Great Britain, about 8% of kids who knew they had a coronavirus infection suffered symptoms that lingered for months. They had fatigue or muscle aches or breathing problems or trouble concentrating in school.

The shots could come as soon as next week after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention makes recommendations on which youngsters should get vaccinated.

Thereâs another big reason to consider vaccinating young kids: getting back to normal.

No one loves wearing a mask all day, or having to spend two weeks in quarantine after being exposed to an infected person. If most kids got vaccinated, a lot of pandemic restrictions would probably get tossed out and kids could resume their normal lives.

Whatâs not to like?

Not everyone sees it this way. Some parents still arenât ready to get their kids vaccinated, and not all experts are sure that every kid needs to be. Over the entire pandemic, the chance that a kid of any age would die of COVID-19 never rose above one in 2 million (and was usually way lower). Thatâs four times less than the odds of being struck by lightning in any given year.

Plus, more than half of young kids with coronavirus infections have practically no symptoms at all. The kids that have been least likely to get very sick or die are the ones between 5 and 11. Babies and teenagers were more likely to get sick if they got infected, and more of them died.

Given all that, these skeptics ask, why would you run the risk of getting every young kid jabbed with COVID-19 vaccine â especially if there are safety issues that researchers donât yet understand?

The closer we get to the end of the pandemic, the harder it is to justify the risk of a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for young children.

A scary heart problem

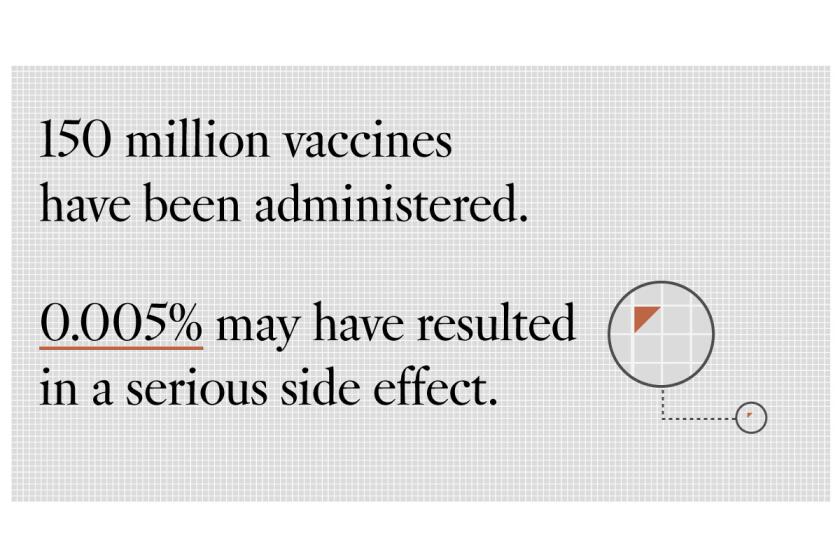

One of the main things the FDA advisors argued about was a rare vaccination side effect that may not even affect kids under 12 after they get this COVID-19 vaccine. The side effect is called myocarditis, and it irritates the heart muscle, causing some swelling and often chest pain.

Myocarditis after an mRNA vaccination is definitely unusual: If you vaccinated 1 million 16- or 17-year-old boys and gave them the adult version of this Pfizer vaccine, about 70 of them would experience some form of the condition. It seems to go away on its own, but if you get it, youâll probably spend several days in the hospital. When these patients get out, theyâll be advised to quit sports for three to six months just to be sure theyâre OK.

The problem is that no one is sure whether myocarditis hurts a childâs heart in any lasting way. Nor do they know whether younger kids who havenât started puberty could get it in the first place. They are counting on the kid-sized dose to be too small to set off any such reaction.

How will we find out?

This is one of the problems that comes with judging the safety of a new vaccine during a public health emergency. To speed the task of making sure this vaccine works safely in young kids, government experts relied on some of the safety data from previous trials and asked Pfizer to test smaller doses in a few thousand kids in the 5-to-11 age group.

Even if myocarditis occurred as often in little kids as it does in teenagers, youâd need more than 14,000 kids in your test group to have one case of myocarditis. With a test group of less than 3,000 kids, odds are good you wonât see any cases.

But that doesnât mean they wonât happen â and no one will know until millions of kids start getting vaccinated.

The idea of marching millions of kids into such an uncertain situation is unnerving to some experts. But the government has a system for keeping tabs on reports of possible vaccination side effects. The FDA assured its advisors that if cases of myocarditis start cropping up, theyâll put vaccinations on hold while they figure out whether thereâs a connection and let people know what theyâve found.

Questions about COVID-19 vaccinesâ safety have led to hesitancy for some Americans. Experts say there is almost zero cause for concern.

Do kids already have some protection?

Maybe. Kids in grade school can catch the coronavirus easily. Even if it doesnât make them sick, their immune systems learn to recognize it so the next time the virus comes calling, their natural defenses can act quickly to shut it down.

A study by researchers at the CDC found that at least 40% of kids are in this category. But since the coronavirus is new, no one is sure how long a childâs immune system will remember it, or how strong the protection will be.

With all this in mind, does it make sense to rush out and vaccinate them all? Some experts donât think so.

Is it over yet?

A lot of adults have been sure the pandemic was just about over, and, boy, have they been proved wrong. Four separate times, weâve seen infections and deaths climb, then fall. And every time so far, theyâve gone back up again.

California has stopped recording week-over-week declines in coronavirus cases and COVID-19 hospitalizations.

But when considering whether most younger kids need the vaccination, it really matters whether the end is in sight. If the virus just canât spread as fast because so many people have immunity, maybe most kids donât need more protection â especially since there may be risks to getting all kids in this age group vaccinated.

On the other hand, if another surge is on the horizon, taking that risk might be a really good way to stop it from happening.

Does the vaccine do more to protect young kids or those around them?

Although most young kids with coronavirus infections donât get sick themselves, they are good at spreading the virus â and it can be hard to tell that itâs happening because they may seem perfectly fine while theyâre doing it. Thatâs a real problem if they live with or go to school with people who could get very sick if theyâre infected.

That includes other kids who have asthma, diabetes or obesity, as well as parents or grandparents whoâve had cancer or chronic heart problems. The young children in these situations probably should get vaccinated to cut off the chain of transmission before it reaches those who are vulnerable.

Youâve heard the term âherd immunity.â Hereâs what it means and why itâs important as we think about returning to something like a normal life.

The kids with these higher-risk health conditions ought to get vaccinated too to protect themselves, experts say.

Why does anyone get vaccinated?

Mostly, to protect ourselves. But also to protect each other.

The more people who get vaccinated, the more protection there is for the most vulnerable among us. For a lot of people, it would be worth running a small risk of a vaccination side effect â even one like myocarditis â to help protect a classmate or grandparent.

One thing is clear: Kids should be protected

Hereâs the last thing worth saying about grown-ups: They love their little kids, and â no surprise here â will defend them fiercely against any harm. Thatâs why some adults whoâve been vaccinated against COVID-19 themselves might need more information before theyâd get their children vaccinated, while others take their kids straight to the pediatrician for their first dose.

Itâs complicated.