Most kids with coronavirus infections lack typical symptoms of COVID-19, study says

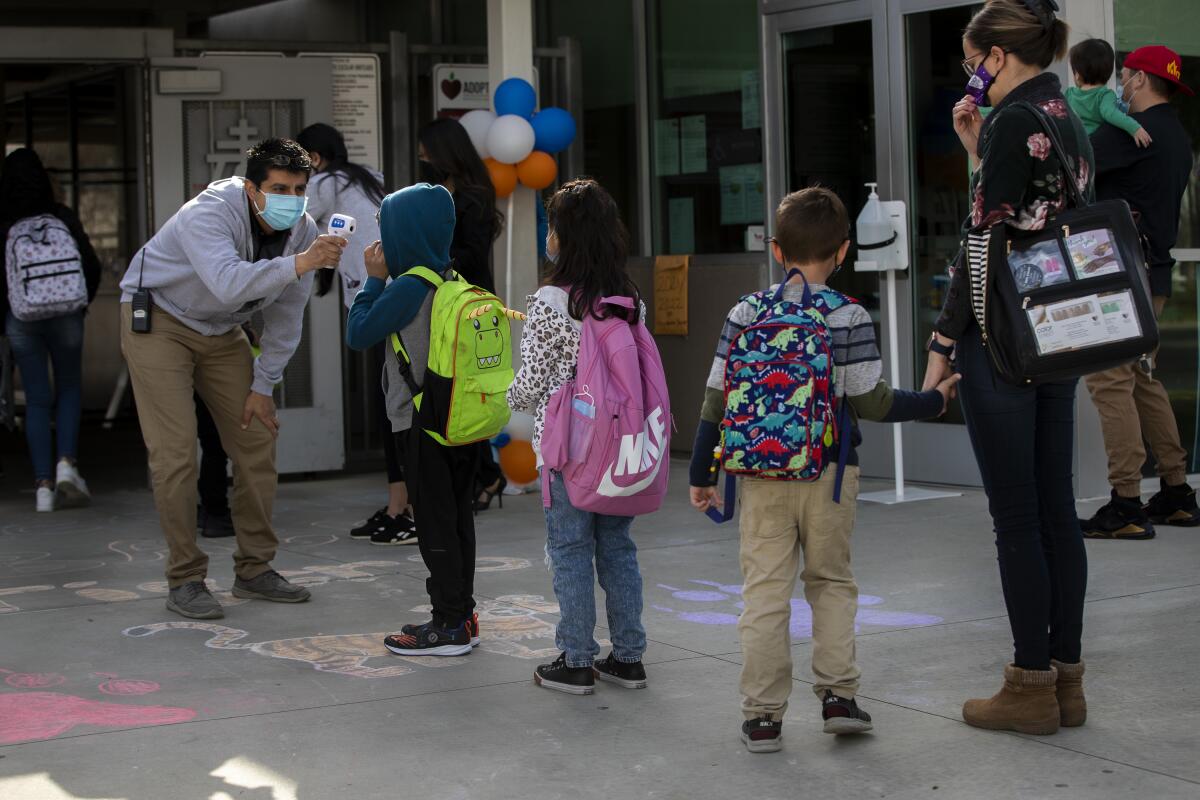

If youâve taken your child to school, a dental appointment or a sports practice in the past year, youâve probably seen someone hold a thermometer up to their forehead or wrist as a COVID-19 screening tool. But a new study suggests that a temperature reading in the normal range isnât a reliable signal that a kid is coronavirus-free.

In fact, the study of more than 12,000 children with laboratory-confirmed infections found that the vast majority of them â more than 81% â did not develop a fever despite contracting the coronavirus.

Whatâs more, nearly three-quarters of these infected children never had âany of the typical COVID-19 symptomsâ â a fever, cough or shortness of breath â researchers wrote Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

On the one hand, the low rate of symptoms in people with bona fide infections is something to be grateful for. But on the other hand, it means that identifying children who could be spreading the virus will be more difficult than previously thought.

âRoutine screening tools and procedures such as daily temperature checks in school may be less effective,â the study authors wrote. Instead, âinnovativeâ screening methods and âfrequent testingâ will be required to identify potential disease spreaders.

Estimates of the number of U.S. children who have been infected by the coronavirus vary. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pegs it at just under 3.2 million since the start of the pandemic, while the American Academy of Pediatrics says itâs more than 3.8 million and the COVKID project puts it above 4.5 million.

Whatever the figure, children have always accounted for a minority of coronavirus cases. Though Americans under the age of 18 account for 19.3% of the U.S. population, theyâre responsible for only 12.3% of the countryâs infections and less than 0.2% of its COVID-19 deaths.

Those figures reflect the fact that COVID-19 is different in kids than in adults. The new study backs that up.

Two studies of hospital workers bolster the case that COVID-19 vaccines really do reduce the risk of a coronavirus infection.

The data come from the electronic medical records of 33 healthcare organizations around the country that participate in the TriNetX Research Network. The records included 12,306 laboratory-confirmed cases of COVID-19 that were diagnosed in patients under the age of 18 between April 1 and Oct. 31 last year.

Perhaps the most striking finding was how few of those patients had symptoms typically associated with COVID-19.

Although itâs primarily considered a respiratory disease, only 16.5% of the pediatric patients had respiratory problems, such as shortness of breath, a cough or wheezing.

In adults, symptoms like fevers, muscle and joint pain, and a general feeling of malaise are also associated with COVID-19, as is the loss of smell or taste. Yet only 18.8% of the kids reported at least one of these symptoms.

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and other gastrointestinal problems cropped up in 13.9% of the young patients, while skin rashes, conjunctivitis and other dermatological symptoms affected 8.1%. Neurological ailments like headaches and convulsions occurred in just 4.8% of the children.

Vaccine hesitancy is making herd immunity for COVID-19 seem more elusive than ever. Could that change once the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is authorized for children as young as 12?

Most symptoms were more common among the 5.5% of patients who required hospital treatment than in the 94.5% who did not. The two exceptions were headache and disturbances of smell or taste.

Of the hospitalized patients, 17.6% (or 118 children) needed critical care and 4.1% (or 38 children) were put on ventilators. Itâs not clear exactly how many died, but it was no more than 10. (Data on deaths was obscured for privacy reasons, the study authors wrote.)

There were some things the children with COVID-19 did have in common with adults.

Compared with white children in the study, Black children were about twice as likely to be admitted to a hospital, and the risk for Latino children was about 31% higher. The odds of needing critical care or mechanical assistance with breathing were about the same for all three groups.

The reasons for these disparities are not clear, but the study authors speculated that socioeconomic forces saddled Black and Latino children with more indirect exposure to the virus â perhaps because they were more likely to live with an essential worker, or they didnât have enough space at home to fully isolate from a family member who was ill.

Despite a statewide mood of optimism, about 57 Californians are still succumbing to the novel coronavirus each day.

Regardless of race or ethnicity, most children in the study did not develop symptoms that would have made their coronavirus infections clear to others. That means adults will need to rethink their screening strategies if they want to spot these kids before they spread the virus to others.

Conducting random testing more often would help, the study authors wrote. So would focusing more screening tests on children from higher-risk households, or on kids with medical conditions that put them at greater risk of serious disease if they become infected.

Itâll be more complicated than aiming a thermometer at a kidâs forehead or asking them if theyâve got a cough, but the work must be done.

âThe reopening of schools underlines the importance of understanding the epidemiology of pediatric COVID-19 infections,â the researchers wrote.