Staying power of coronavirus antibodies bodes well for COVID-19 vaccines, study says

- Share via

Antibodies that people produce to fight the new coronavirus last at least four months after diagnosis and do not fade quickly, as some earlier reports suggested, scientists have found.

The new report, from tests on more than 30,000 people in Iceland, is the most extensive work yet on the immune system’s response to the virus over time and is good news for efforts to develop vaccines.

If a vaccine can spur production of long-lasting antibodies, as natural infection seems to do, it gives hope that “immunity to this unpredictable and highly contagious virus may not be fleeting,” scientists from Harvard University and the U.S. National Institutes of Health wrote in a commentary with the study, published Tuesday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

One of the big mysteries of the pandemic is whether having had a coronavirus infection helps protect against future infections, and for how long. Some smaller studies previously suggested that antibodies may disappear quickly and that some people with few or no symptoms may not make many at all.

The new study was conducted by Reykjavik-based DeCode Genetics, a subsidiary of the U.S. biotech company Amgen, with several hospitals, universities and health officials in Iceland. The country has tested 15% of its population since late February, when its first COVID-19 cases were detected, giving a solid base for comparisons.

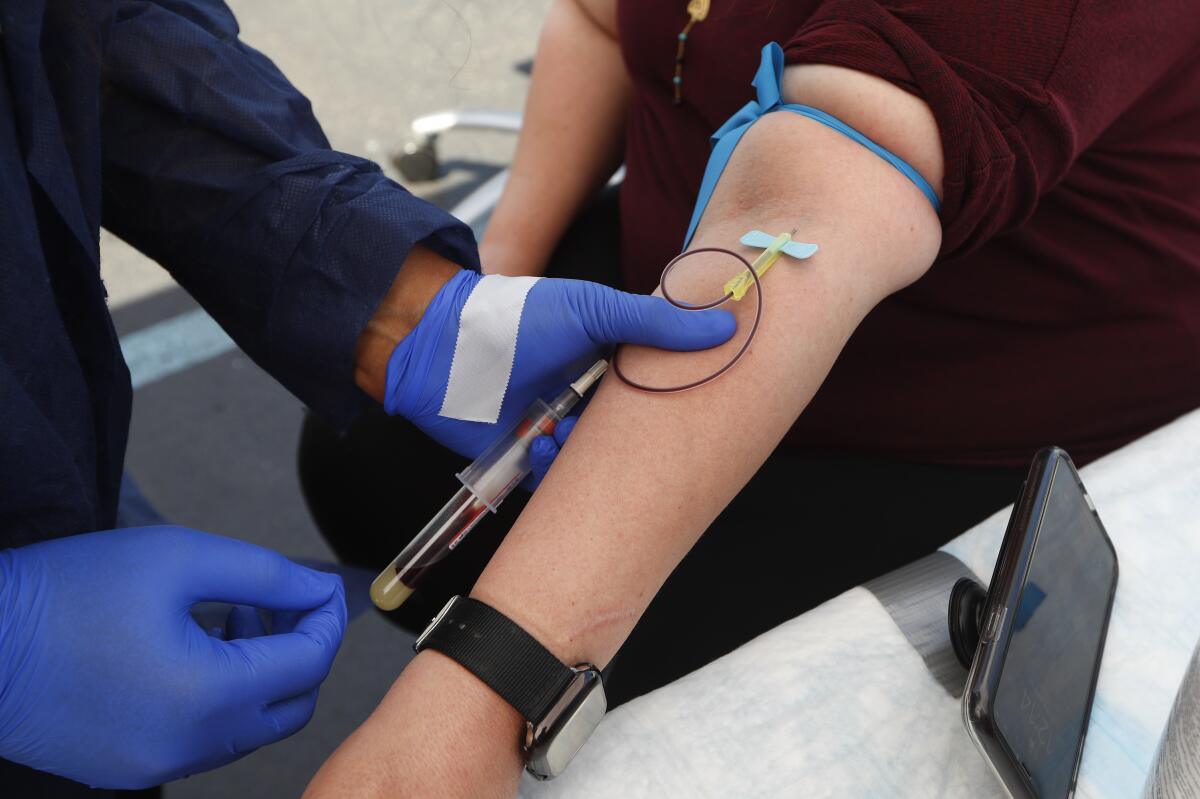

Scientists used two types of coronavirus testing: the kind from nose swabs or other samples that detect bits of the virus, indicating an active infection, and those that measure antibodies in the blood, which can show whether someone is infected or has been in the past.

Blood samples were analyzed from 30,576 people using various methods, and a person was counted as a case if at least two of the antibody tests were positive. These included a range of people, from those without symptoms to those hospitalized with signs of COVID-19.

In a subgroup of people who tested positive, further testing found that antibodies rose for two months after the infection initially was diagnosed, then plateaued and remained stable for four months.

In exploring coronavirus immunity as the nation reopens, scientists still want to know how long immunity lasts and whether it protects everyone equally.

Previous studies suggesting that antibodies faded quickly were mostly focused on the 28 days after diagnosis and may have been looking at just the first wave of antibodies the immune system produces in response to infection. A second wave of antibodies forms a month or two into infection, and this seems more stable and long-lasting, the researchers report.

The results of the study don’t necessarily mean that all countries’ populations will be the same, or that every person has this sort of response. Other scientists recently documented at least two cases where people seem to have been reinfected with the coronavirus months after their first bout.

Still, the news that natural antibodies don’t quickly disappear “will be encouraging for people working on vaccines,” said Dr. Derek Angus, critical care chief at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Other findings from the new study:

• Nearly a third of infections were in people who reported no symptoms.

• Testing through the bits-of-virus method that’s commonly done in community settings missed nearly half the people who were found to have had the virus by blood antibody testing. This means the blood tests are far more reliable and better for tracking spread of the disease in a region and for guiding decisions on returning to work or school, researchers say.

• Nearly 1% of Iceland’s population was infected in this first wave of the pandemic, meaning 99% are still vulnerable to the virus.

• The infection fatality rate was 0.3%. That’s about three times the fatality rate of seasonal flu and in keeping with other more recent estimates, Angus said.

Although many studies have been reporting death rates based on specific groups, such as hospitalized patients, the rate of death among all infected with the coronavirus has not been known.