Disappointing results from two experimental Alzheimer drugs

Two experimental drugs failed to prevent or slow mental decline in a study of people who are virtually destined to develop Alzheimerâs disease at a relatively young age because they inherited rare gene flaws.

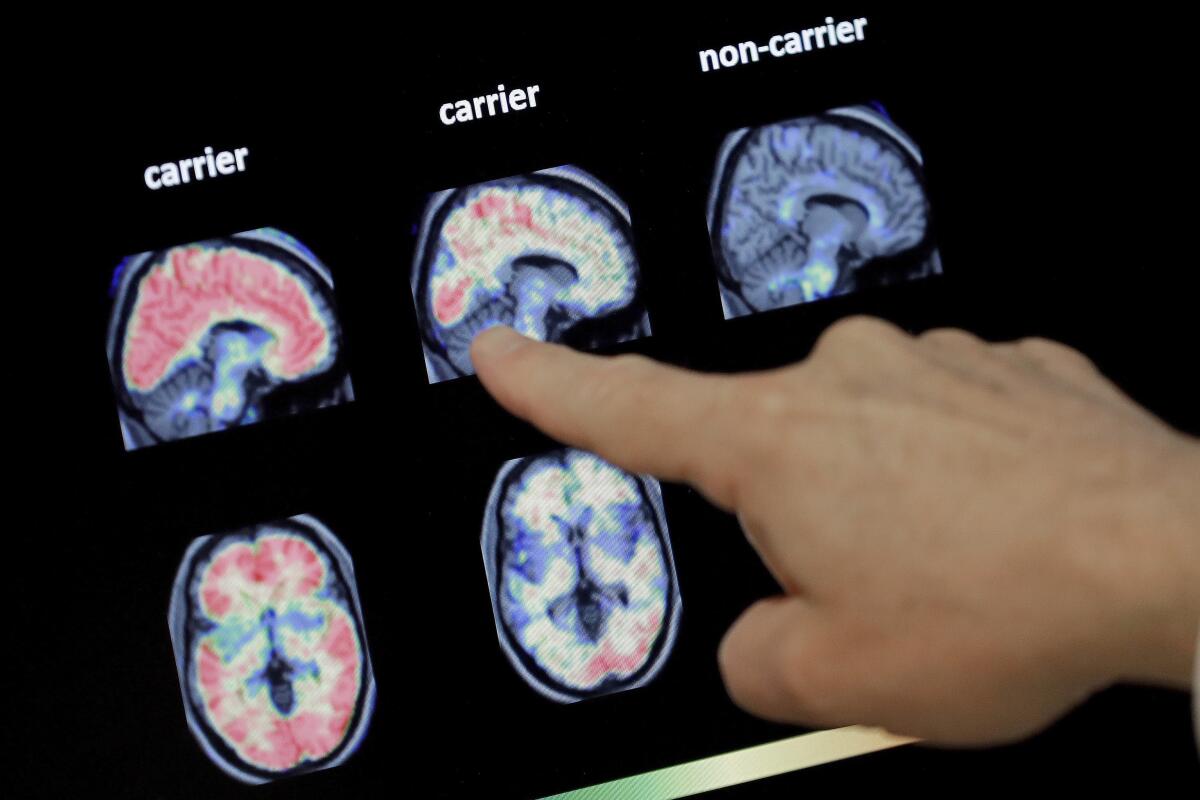

The results announced Monday are another disappointment for the approach that scientists have focused on for years â trying to remove a harmful protein that builds up in the brains of people with Alzheimerâs, the leading cause of dementia.

âWe actually donât even know yet what the drugs didâ in terms of removing that protein because those results are still being analyzed, said study leader Dr. Randall Bateman at Washington University in St. Louis.

But after following patients for an average of five years, the study did not meet its main goal. People on either of the drugs scored about the same on thinking and memory tests as others given placebo treatments, the researchers reported.

More than 5 million people in the United States and millions more worldwide have Alzheimerâs. The drugs available today only ease symptoms temporarily but do not alter the course of the disease.

The study tested solanezumab by Eli Lilly & Co., and gantenerumab by Swiss drugmaker Roche and its U.S. subsidiary, Genentech. Both drugs gave disappointing results in some earlier studies, but the doses in this trial ranged up to four to five times higher, and researchers had hoped that would prove more effective.

The research involved about 200 people in the United States, Europe and elsewhere with flaws in one of three genes.

âIf you get one of these genetic mutations, youâre almost guaranteed to get Alzheimerâs,â typically in your 30s, 40s or 50s, said Dr. Eric McDade, another study leader at Washington University.

People like this account for only about 1% of Alzheimerâs cases, but their brain changes and symptoms are similar to those who develop the disease at a later age. That provides a unique chance to test potential treatments.

âWe know everyone will get sick and we know about what time that isâ in their lives, Bateman said.

Most study participants already had signs of the harmful protein in their brain even if they were showing no symptoms when the study started.

They were given either a gantenerumab shot, an IV of solanezumab, or fake versions of these treatments every four weeks. The drugs made no difference in a combination score of four memory and thinking tests.

Side effects were not disclosed, but âthereâs no evidence of any drug-related deaths in the trial,â McDade said.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Aging, the Alzheimerâs Assn. and some foundations. More details about the results will be shared at a medical meeting in April.

In the meantime, solanezumab is being tested in another trial to see if it can slow memory loss in people with Alzheimerâs. Gantenerumab also is being tested in two other large studies that are expected to have results in two to three years.