A personalized vaccine helps patients fight back against ovarian cancer

In early research that extends the possibilities of immunotherapy to a killer feared by women, a personalized vaccine helped patients with ovarian cancer mount a stronger defense against their tumors and substantially improved their survival rate.

The vaccine was tested in a preliminary clinical trial and used along with standard chemotherapy and an immune-boosting agent.

The experimental therapy, described this week in the journal Science Translational Medicine, weaves together a number of approaches that are collectively driving innovations in cancer treatment.

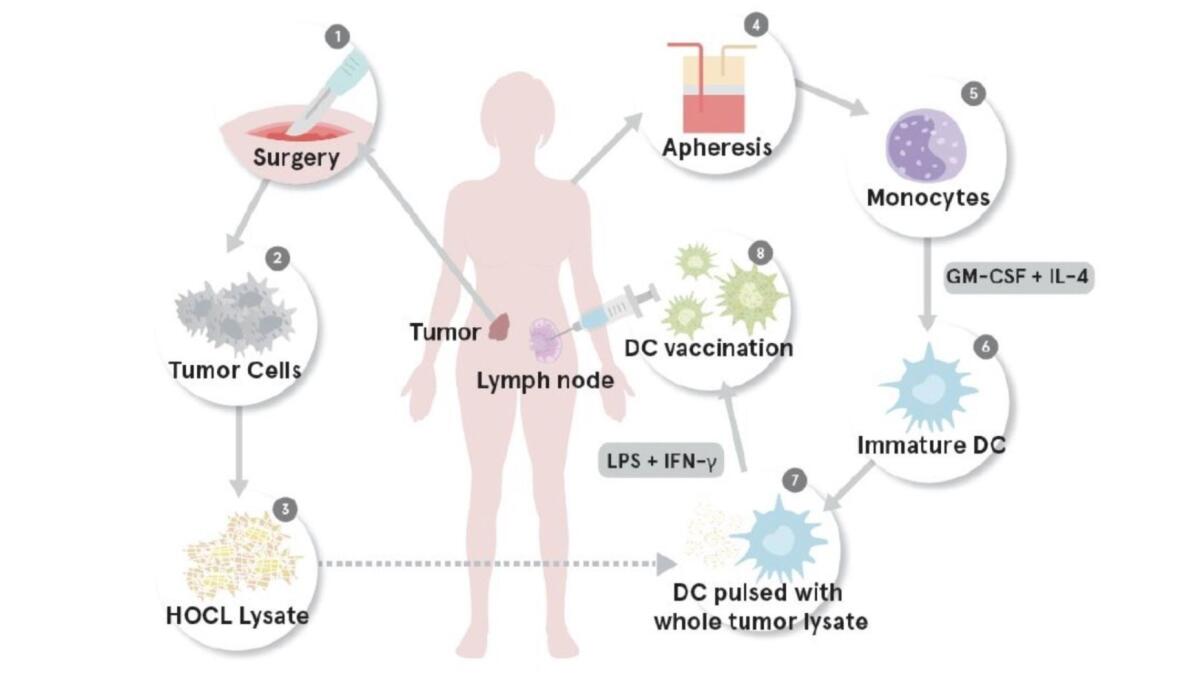

Because the treatment uses the patientâs immune cells as a sort of T-cell training force, it is an immunotherapy. Because it uses the distinctive proteins on a patientâs own tumor as homing beacons, it is a targeted therapy. And because a patientâs own cells are harvested and returned to her, it is personalized therapy.

Rather than round up a patientâs T cells and re-engineer them in a lab to find cancer (the service provided by the new leukemia immunotherapy drug Kymriah), this treatment harvests a class of immune âhelpersâ called dendritic cells. Using ground-up cells from a patientâs tumor, researchers trained the dendritic cells to recognize and attack that specific malignancy. When these fortified cells were reintroduced into the patient, they passed on their training to the immune systemâs army of killer T cells and sent them into battle.

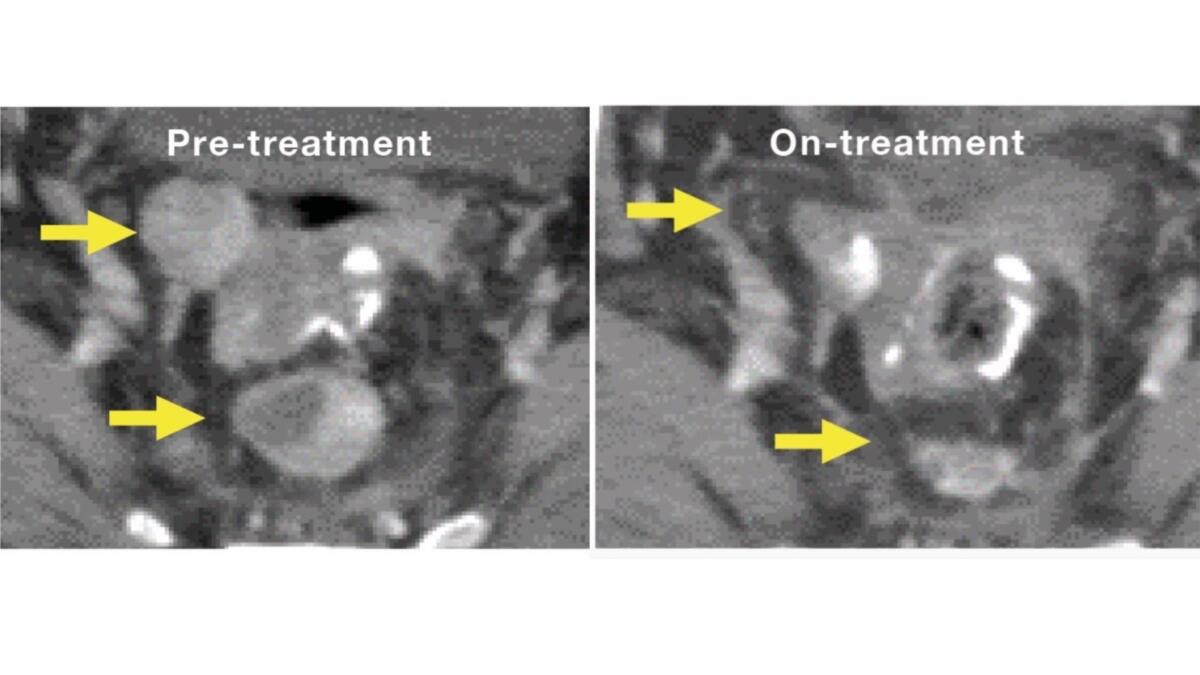

Among 10 women with advanced ovarian cancer who got injections of the personalized vaccine once every three weeks â along with the medications cyclophosphamide and bevacizumab (marketed as Avastin) â eight showed a strong immune response and were still alive after two years.

In a comparison group of 56 patients that got standard chemotherapy alone, only half were still alive at the two-year mark.

Among a second cohort of 10 patients who got bevacizumab and dendritic cell vaccine alone (but no cyclophosphamide), only 30% survived to the two-year mark.

The studyâs primary aim was to test the safety of the vaccine in combination with the other drugs.

Among these study subjects, as well as in subsequent cohorts of research subjects, the vaccine has been âso safe itâs unbelievable,â said study leader Dr. Janos L. Tanyi, a gynecologist at the University of Pennsylvania. At worst, subjects have reported brief bouts of tiredness or flu-like symptoms, he said.

The same approach may also prove helpful in combating solid tumors in different organs, Tanyi said.

If ever there were a cancer ripe for a more effective new treatment, itâs ovarian cancer. As the fifth-leading cause of cancer death in the United States â and the most deadly of gynecological cancers â it claimed the lives of more than 14,000 American women in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because there is no effective screening mechanism for ovarian cancer, itâs often not detected until it has reached an advanced stage. For 85% of women in whom it is diagnosed, a combination of surgery and chemotherapy does not succeed in driving the malignancy into remission, and it recurs.

A personalized ovarian cancer vaccine is likely years away from widespread use in patients. Scientists will likely have to find a way to make larger supplies of vaccine with a limited supply of tumor cells, Tanyi said. Meanwhile, researchers are already finding new ways to enhance the vaccineâs effectiveness, he added.

As in other immunotherapy trials, Tanyi has found that some patients were able to halt their cancerâs progression with continued booster shots of vaccine. For some women, the vaccine appears to have driven the cancer into remission entirely.

Tanyi says he is eager to explore whether the dendritic-cell vaccine might also be used as a first-line treatment for women who are newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer. In order to supply tumor cells for the vaccine, such patients would still have to undergo surgical removal of their tumors.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Bad news for night owls. Their risk of early death is 10% higher than for early risers, study finds

What ails America? The answer varies from state to state

A finger bone from an unexpected place and time upends the story of human migration out of Africa