Catchy tune caught in your head? Try chewing gum

- Share via

A new study suggests that if you want to get an annoying song out of your head, chewing a piece of gum might help.

It turns out that just the mechanical act of moving one’s jaw up and down can reduce the number of times people think about a catchy song, as well as how often they “hear” that song playing in their minds.

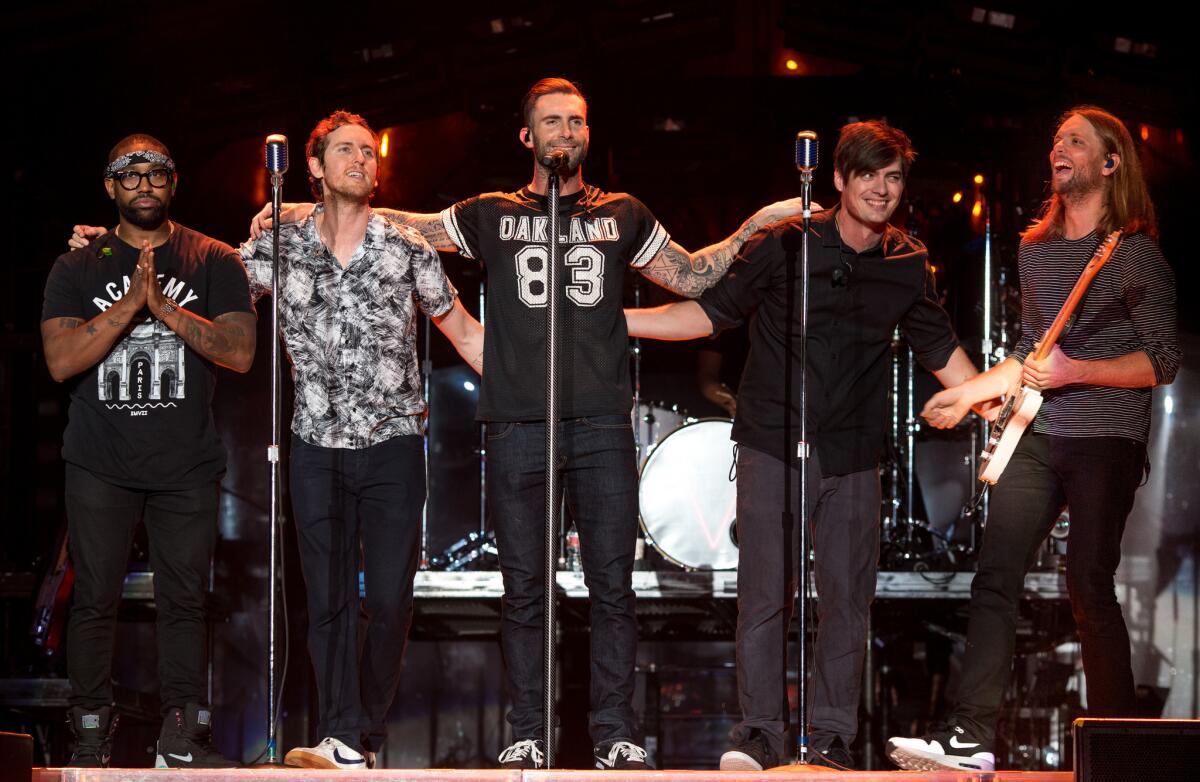

To be clear, this method is not a silver bullet. In a series of three experiments, the researchers found that volunteers who were given chewing gum and instructions to “chew vigorously” after hearing particularly “sticky” music, such as the chorus of David Guetta’s “Play Hard” or “Payphone” by Maroon 5, experienced fewer phantom memories of the songs, but not zero.

Still, the researchers say chewing gum is a tactic worth trying if you can’t stop singing a song such as “It’s a Small World After All” to yourself after a visit to Disneyland.

“If you are trying to rid yourself of an unwanted tune, it is less likely to pop up involuntarily when chewing,” said Philip Beaman, associate professor of cognitive science at the University of Reading in England, and the lead author of the report.

Tunes that get stuck in your head are known as earworms, and they have been plaguing humanity for a long time. In 1845, Edgar Allen Poe wrote that it is “quite a common thing” to be “annoyed” or “tormented” by “the ringing in our ears, or rather in our memories, of the burthen of some ordinary song.”

These “burthen”-some musical memories have received a bit of scientific study in the recent past. For instance, research has shown that people with greater cognitive function experience earworms for a shorter duration than their less cognitively capable peers.

In addition, a 2012 study found that when volunteers focused their mental attention on another task after being played a particularly sticky tune, they were able to reduce the incidence of earworms -- but only if the task was neither too challenging or too simple.

Beaman was inspired to look into the gum chewing angle after happening upon an anonymous comment on the Exploratorium’s website that claimed chewing on a cinnamon stick can keep a song from getting stuck in one’s head.

“What was interesting to me is that ‘chewing cinnamon sticks’ was very much consistent with what I already knew about how planning and producing movements of the mouth and jaw affects memory and the ability to imagine music,” Beaman said.

Previous studies had shown that mouthing something random like the first few letters of the alphabet while looking at a list of words makes most people forget 1/3 to 1/2 of the words on the list. Mouthing words had also been shown to interfere with auditory memory -- for example, making it difficult to remember if the fourth note in the Happy Birthday song is higher or lower in pitch than the third note.

Beaman wanted to test if the act of chewing could inhibit a person’s ability to generate what he calls “auditory images.”

In the first of three experiments, Beaman and his team played for 40 undergraduate students the first 30 seconds of the song “Play Hard” twice, and then told them to try to think about anything they liked, except the song, for a period of three minutes. Whenever the song popped into their head anyway, the students were told to press the “q” key on a keyboard.

When those three minutes were up, the students were told they could think about anything they liked, including the song, but they were still asked to press “q” when they thought about the song.

The students all participated in the experiment twice -- once while chewing gum vigorously after listening to the music, and once with no gum.

When the students were not chewing gum, they reported thinking about the song an average of nine times during the first three-minute period, and an average of 10 times during the second three-minute period. But when they were chewing gum, the number of times they thought about the song dropped to an average of just over six times during both periods.

A second experiment showed that chewing gum has more of an effect on “hearing” a song in one’s head rather than just thinking about it.

In this experiment participants were told to press “q” when the song came to their minds as a thought and “p” when they heard the song playing in their heads.

On average, volunteers who were not chewing gum reported thinking about the song an average of twice in a three-minute period and hearing it playing in their minds six times in the same time period. When they were chewing gum, the average number of times they thought about the song remained statistically the same, but the number of times they heard it in their minds fell to four times in three minutes.

In the final experiment, the researchers wanted to test if the effects of chewing gum on earworm frequency could be duplicated by another mechanical action, such as tapping on a table.

In this case, those participating in the control scenario (no chewing, no tapping) reported thinking about or hearing the song 12 times in two minutes, the tapping group thought about the song an average of seven times a minute and the chewing group thought about it just over four times a minute.

“Experiment 3 rules out the possibility that the effect observed is a general effect of motor activity,” the researchers conclude in the paper published this week in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology.

In the future, Beaman said he’d like to study how long the effects of gum chewing last on earworm interference, and whether the catchy tune comes back into people’s heads after they spit the gum out. He’d also like to know if gum can help rid people of a scary noise that got stuck in their head.

(I was hoping chewing gum might help mitigate scary images that get stuck in our minds, but Beaman said gum chewing applies to auditory images only).

He also adds that this research provides no insight on what tunes eventually become earworms. “It seems to be highly idiosyncratic,” he said. “Although the theme from ‘Frozen’ crops up quite a lot in self-report.”

Science rules! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.