Coronavirus Today: Teens for vaccines

Good evening. Iâm Karen Kaplan, and itâs Tuesday, Jan. 25. Hereâs the latest on whatâs happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Ask a teenager what she wishes her parents would give her and you might expect an answer like âa new iPhoneâ or âa car of my own.â Ani Chaglasian, a 17-year-old high school junior from Glendale, wanted something quite different: permission to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

As long as she was unvaccinated, she couldnât attend extracurricular activities at school. She lost her job as a medical scribe at a local hospital. She was terrified that sheâd inadvertently spread the coronavirus to older relatives, including her grandmother with lung cancer.

Ani spent much of 2021 lobbying for the chance to get the shots. Though public health officials at all levels endorsed the vaccine, their united front didnât impress Aniâs parents. In their Armenian American community, itâs not uncommon to be highly skeptical of government pronouncements.

She tried her best to change their minds. She explained the science behind the shots and cited data showing they were safe. She told her dad she wouldnât be able to live with herself if she became a link in a viral transmission chain that resulted in his death. She begged.

If Ani lived in Philadelphia, or Washington, D.C., none of this would have been necessary. In those cities, children 11 and up donât need a parentâs permission to get vaccinated.

California may follow their lead. State Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) introduced a bill last week that would let adolescents 12 and older to make their own decisions about vaccines that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They wouldnât even have to let their parents know they were immunized.

If Senate Bill 866 is passed by the Legislature and signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, it would go into effect on Jan. 1.

Wiener doesnât see the bill as a huge departure from current state law, which allows Californians 12 and older to make their own decisions about reproductive health. That includes the authority to get the human papillomavirus and hepatitis B vaccines.

âThis is about empowering teenagers to make decisions on their own health and their own safety,â Wiener said. âAlmost a million California teenagers are unvaccinated, and for a lot of those teens itâs because their parents either refuse to get them vaccinated or they have not yet gotten around to it.â

Alabama went in the other direction. State law there allows teens who are at least 14 to provide consent for their own medical treatment, but a new bill carved out an exception for vaccines. Gov. Kay Ivey signed it into law in November.

In California, minors are likely to remain at the mercy of their parents for the rest of the year â at least. Fortunately for Ani, she was finally able to persuade her parents to sign off on her COVID-19 shots. As a bonus, she convinced them to get vaccinated as well.

Ani got help from Teens for Vaccines, an organization founded by Arin Parsa in pre-pandemic 2019 after he heard a teenager tell members of Congress how misinformation turned his mother into an anti-vaxxer, leaving him unprotected against diseases like measles and polio.

Now 14, Arin scans vaccine-related posts on Reddit looking for questions he can answer and peers he can encourage. For instance, when he encountered a 16-year-old from Ohio who wondered whether he could get vaccinated against his parentsâ wishes, Arin told him he would need their consent and directed him to an online guide he created to help teens change their parentsâ minds.

About three dozen kids across the country have joined his effort as Teens for Vaccines ambassadors. In addition to Ani, they include a sophomore from Texas whose QAnon-supporting parents wonât let her get the shots and a senior from Louisiana who didnât take COVID-19 seriously until the disease caught up with him and he learned it was ânot a joke.â

Arinâs campaign has been fulfilling at times, frustrating at others.

âWeâre tired of this pandemic, weâre tired of the infighting,â he told my colleague Marisa Gerber. âCan we set it aside and just fight COVID? Itâs overdue that we get our lives back.â

By the numbers

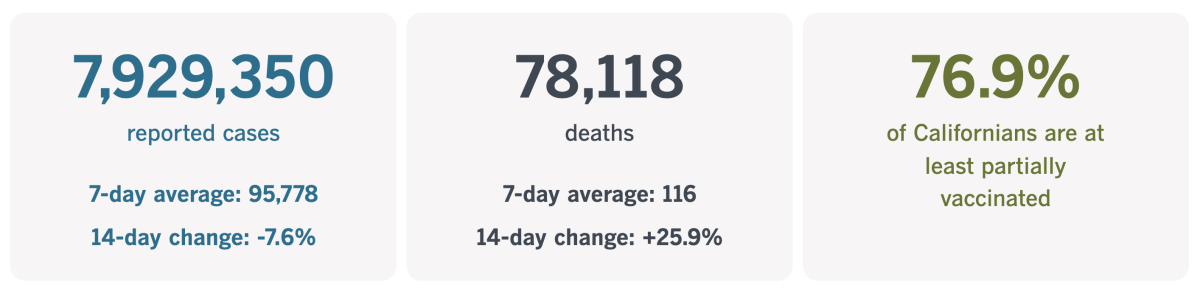

California cases and deaths as of 5:46 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track Californiaâs coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts â including the latest numbers and how they break down â with our graphics.

The impossible cost of COVID-19

You know that COVID-19 has torn holes in families. You know its damage extends beyond the people who become sick themselves. You know the pandemic has been particularly hard on young people trying to come of age in an unsettling time of invisible danger and physical distancing.

But youâll really know all these things after youâve read this heartbreaking story by my colleague Brittny Mejia.

The story is about two generations of men named Anthony Michael Reyes. They hailed from Murietta in Riverside County, and even for a father and son, they were particularly close.

Anthony Sr. was a power plant operator; Anthony Jr. was a high school senior who planned to work in the same plant after graduation. The younger Anthony became a wrestler because the older Anthony had been a wrestler. The two shared the same smile, the same laugh. They were best friends.

âHe was just like Anthony,â Nicole Mulgado, Anthony Sr.âs sister-in-law and Anthony Jr.âs aunt, said of the younger man. âIt was like a copy and paste.â

Another thing the two had in common: Both had health conditions that put them at greater risk of becoming severely ill if they caught the coronavirus. For Anthony Sr., it was a heart condition. For Anthony Jr., it was asthma. Although their medical vulnerabilities made them prime candidates for COVID-19 vaccines, the family shied away from them for fear of side effects.

The first year of the pandemic was difficult for Anthony Jr. Wrestling was on hold. He couldnât see his girlfriend. Heâd stay in bed until the last minute before joining his classmates on Zoom. Sometimes he didnât bother changing out of his pajamas first.

âWith everything being closed, it was becoming increasingly harder to stay home with my depression,â he wrote in a school paper.

This is what U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy was talking about in December when he issued an unusual public health advisory about the mental health crisis among Americaâs youths.

âThe pandemic eraâs unfathomable number of deaths, pervasive sense of fear, economic instability, and forced physical distancing from loved ones, friends, and communities have exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced,â Murthy wrote.

Anthony Jr. was doing better by August. His school had resumed in-person classes, and he was excited to be among the âtop dogs,â his mother, Stephanie, said. On Aug. 27, he attended the first sports pep rally of his senior year.

Soon after, the school shared some troubling news: One of the Reyes children had been in contact with someone who tested positive for a coronavirus infection.

Thatâs when everything changed.

It took only a few days for the entire family â Anthony Sr., Stephanie, Anthony Jr. and his sisters, Marissa and Reyna â to become sick with COVID-19. Within a week, Anthony Sr. was on a ventilator. He died on Sept. 11.

The last time Anthony Jr. saw his fatherâs body in the hospital, he noticed the blood pooled in the corner of one eye. It was an image he couldnât forget.

Sometimes he blamed himself for his fatherâs death, thinking he was the one who brought the virus home to his fragile family. Sometimes he yelled at photos of Anthony Sr. and demanded, âWhy did you leave us?â

Stephanie tried to get help for him and his sisters, but it would take months to get an appointment with a therapist.

Two days after Christmas, Anthony Jr. went to the gym with his best friend. When he came home, he thanked one of his sisters for help with his laundry. He told his mother he loved her before heading to bed.

Stephanie jolted awake before dawn the next morning. She saw light beneath Anthony Jr.âs door. When she opened it, she discovered that he had taken his own life.

âFive months ago, I had my whole family together, safe,â she told Mejia. âThe pain of losing a best friend is bad. But losing my baby is the worst pain I have ever been in.â

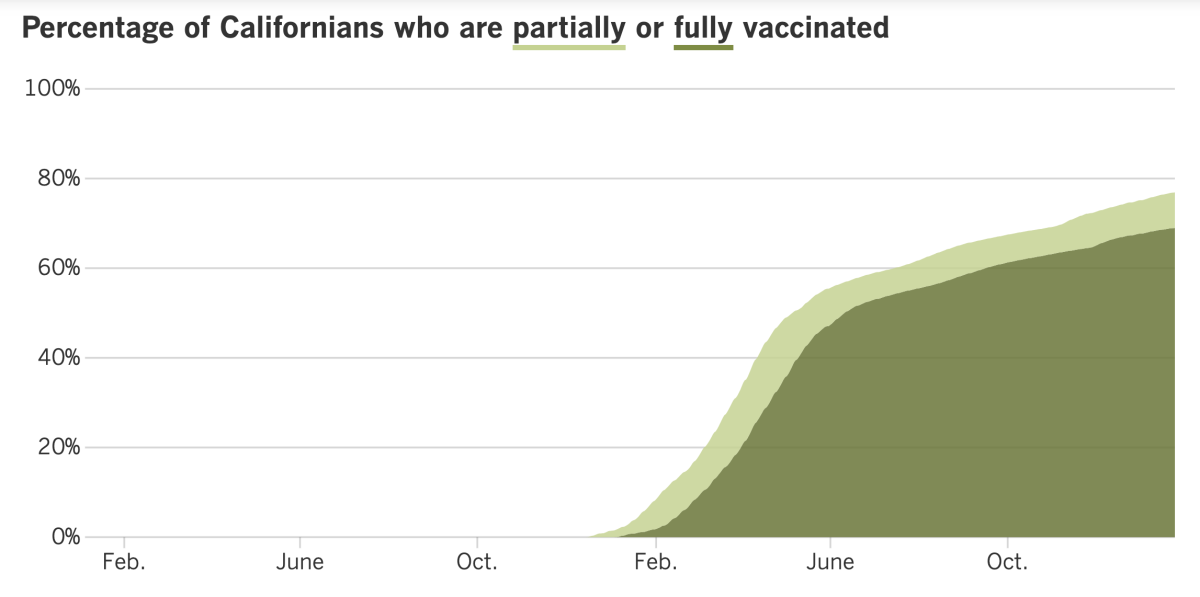

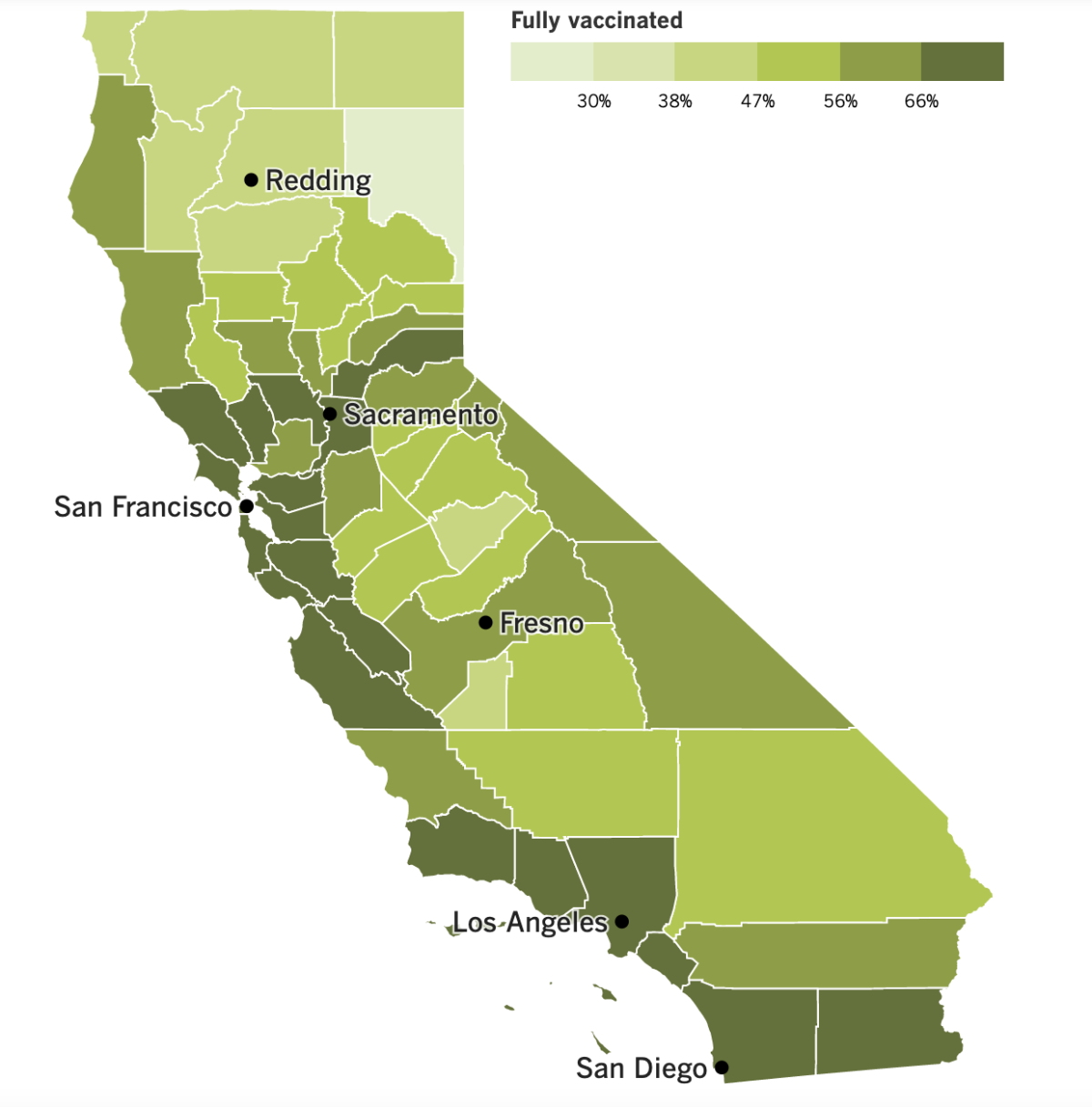

Californiaâs vaccination progress

See the latest on Californiaâs vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

The Omicron wave may be showing signs of slowing down in Los Angeles County, but the daily death toll is still rising.

Deaths from COVID-19 in the nationâs most populous county have soared in the last week. As of Tuesday, the county was averaging 57 deaths per day over the last seven days. Thatâs 162.5% higher than it was two weeks ago, according to the Times Tracker.

For the sake of comparison: The initial surge in 2020 maxed out at 50 deaths per day; the surge during the pandemicâs first summer climbed as high as 49 deaths per day; and the Delta surge (which thankfully came along after COVID-19 vaccines were widely available) topped out at 35.

L.A. County reported 102 deaths on Thursday, the highest single-day total since March 10, when the devastating fall-and-winter surge was winding down. The vast majority of those people became sick after Omicron had become the countryâs dominant strain.

âWeâre still walking through ⌠the shadow of the valley of death right now when we see 100-plus people in my city, my county, die in a single day,â L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti said. âAnd somehow thatâs become normalized, or we donât think about it as hard as we used to. I do. I still think about it.â

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Omicron is killing its victims more quickly than earlier variants did. When Delta reigned, the typical time between the onset of COVID-19 symptoms and a patientâs final breath was four to five weeks. Now, itâs about three weeks or less.

âThatâs a relatively short period of time between the time somebody gets infected, gets their symptoms and then passes away,â she said.

No one wants to catch Omicron, of course, but Tuesday brought some encouraging news for those who do get sick: More days of paid sick leave may soon be available for California workers.

Gov. Gavin Newsom reached a deal with state lawmakers to restore up to 80 hours of paid leave for COVID-19 patients. That matches the requirement of a law from 2021 that expired on Sept. 30. The paid time off can also be used to care for a loved one who is sick with COVID-19.

The new law would apply to businesses with at least 26 employees, and companies would have to absorb the cost. The deal includes tax credits to help offset the added expense.

Labor unions pushed for the return of longer paid leave, and state officials hope it will encourage sick workers to stay home and limit the virusâ spread. Business groups pushed to require a positive coronavirus test to qualify for Hours 41 through 80 of sick pay.

The legislation is likely to be fast-tracked and sent to the governor in a matter of weeks. If it passes, it will be retroactive to Jan. 1 and remain on the books until Sept. 30.

Lawmakers in Sacramento â particularly Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a pediatrician â are also working to pass some of the strongest COVID-19 vaccine legislation in the country. In addition to the bill that would allow adolescents to consent to the shots, thereâs another that would essentially make it moot. SB871 would add COVID-19 vaccines to the list of required immunizations for students attending K-12 schools and only offer exemptions to children with a legitimate medical reason to skip the shots.

Another bill in the works would require people to be vaccinated to set foot in California schools, workplaces, restaurants, and other public venues like malls and museums â and it would be much harder to evade the requirement by claiming some kind of exemption. Thereâs even one under consideration that would hold tech companies accountable for allowing misinformation about vaccines to spread on social media platforms.

Anti-vaccine activists are fully aware of this activity and are vowing to fight back. They acknowledge they may not succeed in a state as blue as California, but they expect their efforts will gain them followers elsewhere.

âThe point of these rallies and protests is to bring more people into the fold, from all around the country,â said Stefanie Fetzer, who has organized anti-vaccination demonstrations in years past. âSen. Pan galvanized a larger anti-vax movement that wouldnât have happened without him.â

Speaking of vaccines, the Biden administration has formally withdrawn its rule that would have required people at companies with at least 100 workers to either get the shots or submit to regular coronavirus testing. The move was something of a formality after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration didnât have the authority to institute the vaccine mandate.

Some large employers â including Starbucks and General Electric â withdrew their own vaccine mandates in light of the high courtâs decision. But others, like Citigroup and Carhartt, are keeping theirs in place.

Pfizer and BioNTech said Tuesday that theyâd kicked off a clinical trial to test a new version of its COVID-19 vaccine thatâs specially designed to target Omicron. The study will enroll up to 1,420 people ages 18 to 55 and compare the new formulation with the original version thatâs already FDA-approved. The new vaccine will be assessed for use as a booster and as a primary immunization. It could take months for full study results to come in.

In Israel, an expert panel has recommended a second COVID-19 booster shot for everyone 18 and older. That would bring the total number of doses to four.

Panel members cited research that showed a fourth dose provided double the infection protection of three doses. It also helped reduce the risk of severe illness, they said. A fourth dose is already available to high-risk Israelis, including those older than 60.

And in France, a new law went into effect Monday that excludes unvaccinated people from restaurants, bars, tourist sites and sports venues (unless they have proof theyâve recently recovered from a case of COVID-19). A negative coronavirus test result will no longer cut it.

Your questions answered

Todayâs question comes from readers who want to know: Why canât people on Medicare get reimbursed for buying COVID-19 test kits?

This question was prompted by the Biden administrationâs announcement that, as of Jan. 15, health insurance companies must pay for up to eight coronavirus tests per month for each person they cover. And thatâs the crux of the problem for Medicare beneficiaries: Traditional Medicare is not a health insurance company.

Sure, it functions like a health insurance company in many respects. Enrollees pay a monthly premium, and the program covers the cost of doctor visits, hospital stays, prescription drugs and the like. If a doctor orders the kind of coronavirus test thatâs processed by a lab, Medicare will foot the bill.

But the government health insurance program for Americans 65 and older is governed by federal law. And that law does not allow the program to pay for over-the-counter tests people use to diagnose themselves.

Under the law, Medicare Part A pays when patients are treated in hospitals, nursing homes or hospices, as well as for home healthcare. Part B pays for doctorsâ services, whether itâs a routine physical or coronary bypass surgery. (Certain medical supplies are covered under Part B as well.) Medicare Part D handles prescription drugs.

You may have noticed we skipped Medicare Part C. This is an alternative to traditional Medicare that came along in 1997, and these plans (now known as Medicare Advantage) are administered by private companies. Some of these companies might reimburse enrollees for COVID-19 tests they buy themselves. If you have Medicare Advantage, youâll have to ask your provider if youâre eligible.

For what itâs worth, the reimbursement rule doesnât apply to people on Medicaid either, or to those who are uninsured. The Biden administration aims to help those in the latter group by sending up to 50 million home test kits to community health centers.

Also, remember that everyone is eligible to request four free rapid test kits at COVIDtests.gov. You can reread Fridayâs reader question for a refresher on why itâs a good idea to order them even if youâre vaccinated and feel completely healthy.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and weâll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your questionâs already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Hereâs where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Hereâs what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

Weâve answered hundreds of readersâ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.