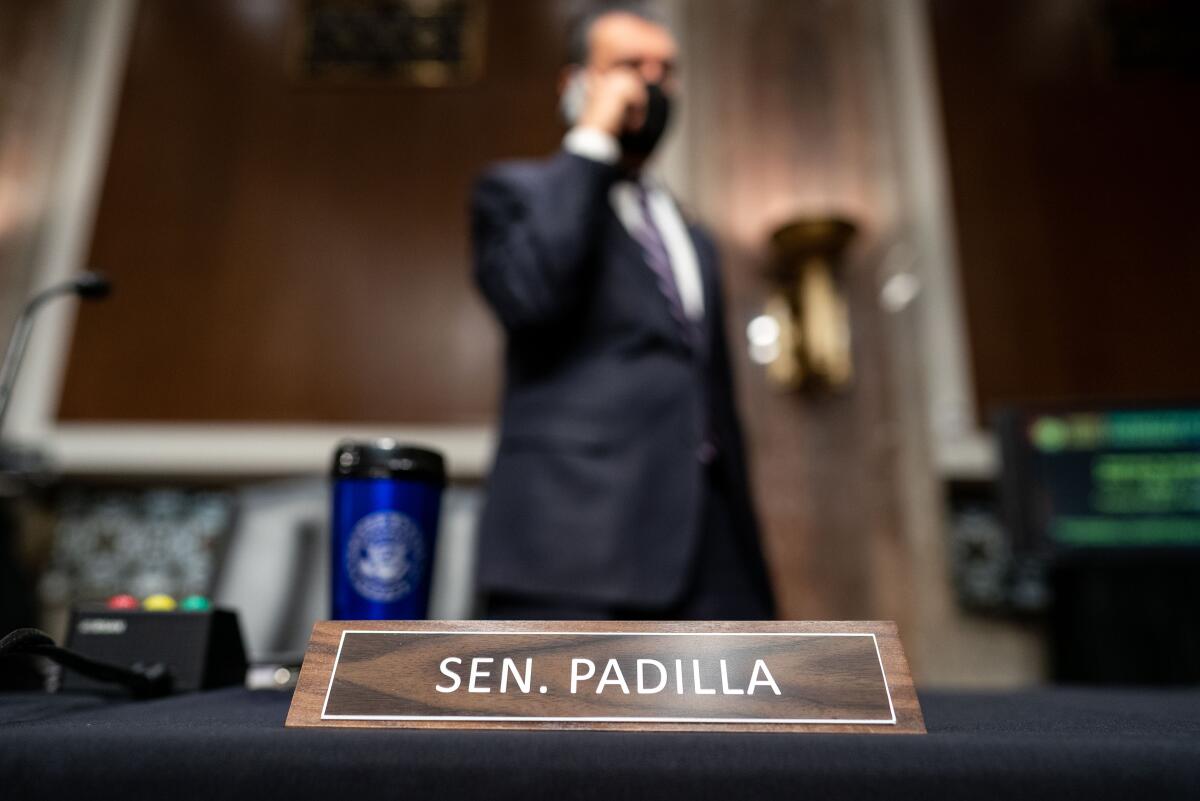

Column: âItâs not as bad as it looks.â Alex Padilla on life in the Senate, and spicing up Capitol Hill

SAN FRANCISCO â Less than a year and a half in office, Alex Padilla has already made his mark in the U.S. Senate.

Last summer, when the dining room on the north side of the Capitol ended its pandemic-related closure, Padilla arrived wielding a bottle of TapatĂo, the hot sauce native to the Los Angeles area.

Change comes slowly to the Senate, a sclerotic institution that still has a pair of spittoons on the floor because, well, tradition. But the manager of the dining room immediately agreed to add the zesty condiment to the menu, ending the requirement that lawmakers bring their own heat and instantly elevating the quality of the Senateâs famous, if bland, bean soup.

Granted, itâs not the sort of thing that gets your name slapped on a congressional office building or inscribed on the pages of history. But itâs a start.

In truth, Padilla has been doing a lot more adjusting to the Senate than the other way around.

Proponents of mandatory voting say it would strengthen democracy and make Americaâs politics less awful.

He was Californiaâs secretary of state when Gov. Gavin Newsom chose him to replace fellow Democrat Kamala Harris after she assumed the vice presidency in early 2021. Padilla has been accommodating himself to changes ever since â to life under a scattershot schedule, to long periods away from his wife and three boys, to the joys of a 4,600-mile round-trip commute several times a month.

Not that heâs unhappy or regretful. Padilla will be on the ballot twice in June, seeking to finish Harrisâ term, which ends in January, and, separately, to obtain his own six-year lease on the Senate seat through 2028. Heâs strongly favored to win.

âPublic service comes with sacrifice,â he said during a conversation about the personal aspects of his first year and three months in Washington. He sat high over San Francisco, in one of his several district offices, with a postcard view of the Transamerica Pyramid and Coit Tower behind him.

The hardest thing about life in the Senate, Padilla said, has been the separation from his family. They remain at home in Porter Ranch in the San Fernando Valley, while Padilla rents a studio apartment a few blocks from Capitol Hill.

His boys are 7, 9 and 14. Padilla, a former L.A. city councilman, prided himself on being the kind of dad who attended not only his boysâ sporting events but many of their practices as well. Not anymore. Heâs also missed Christmas recitals, was gone for the first time ever on his wedding anniversary (No. 9), and spent his most recent birthday attending the second installment of Ketanji Brown Jacksonâs Judiciary Committee hearings.

When Padilla got back to his apartment after the marathon session, his wife and kids called to wish him a happy 49th. All he wanted to do was go to bed.

Not that life in dual time zones or the long-haul commute were entirely unexpected. Going into the job Padilla got plenty of advice, and warning, from Harris, former Sen. Barbara Boxer and the stateâs senior U.S. senator, Dianne Feinstein, among others. Their tips were both practical (Always book a backup flight in case you miss the first) and pointed (You may be new to the Senate, but youâre from California. Donât be afraid to speak up).

From the outside looking in, the Senate seems like an awful place, a slough of petty squabbling, partisan backbiting and oversized egos on the march.

But Padilla insisted that away from the TV cameras âitâs not as bad as it looks.â True, there are senators like Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley who seem mainly focused on performing stunts and positioning themselves to run for president. But there are many more, Padilla said, âtrying to find common ground to try to work across the aisle.â

He cited his joint effort with Texas Republican John Cornyn to pass legislation to help weatherproof the countryâs electrical grid, and his work with Oklahoma Republican James Lankford to improve healthcare for Native Americans.

âI havenât gone out for many beers with Republicans,â Padilla said, âbut a coffee here, a lunch there in an effort to both get to know and get to be known.â

A repeat of 1992âs âYear of the Womanâ seems unlikely, given todayâs higher threshold for outrage.

The Senate, for all its imperfection, is also a place of great history and moment.

Padilla thumbed through his phone and brought up a photograph from last spring, when a bipartisan group of face-masked lawmakers gathered in the Oval Office to discuss President Bidenâs massive infrastructure proposal. âMy assigned seat was the chair right next to the Resolute desk,â Padilla said, referring to the oak monolith used by many presidents.

A feeling came over him. It was, he said, one of those can-you-believe-it things: a kid from Pacoima, a graduate of public schools, the son of Mexican immigrants, the first Latino senator in California history, perched among a group of lawmakers helping shape legislation touching the life of just about every American.

âIâm thinking of my parents,â Padilla said, âlike, Iâm in this room at this moment.â

Then Padilla remembered the reason heâd come to the White House, to make his case for such priorities as water policy and expanded broadband access.

The reverie, he said, had to wait. There was work to do.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.