KABUL, Afghanistan â His hair in a bun, face shadowed by his hoodie, Jawad Sezdah raps with his âhomiesâ about Afghanistanâs darkening future.

He and his friends sit in a circle at what they call their club, a second-floor makeshift studio in west Kabulâs Pul-e-Surkhta neighborhood. They smoke weed, drink tea and practice freestyle lyrics. A picture of Tupac Shakur is taped on the wall.

But the lives the 22-year-old Kabul University student and others of his generation have forged in the nearly two decades since America invaded their country are at risk as never before. The U.S.-led invasion has brought the trappings of the West and a small degree of its promised freedoms, but many here are fearful those gains are about to evaporate.

They are a generation not so much adrift as stuck between opposing forces. They live with fresh graves and echoes of firefights and marketplaces spoiled by suicide bombers. Theirs is land that has not been conquered, a nation that has attuned them to hardship and the hope that the Taliban and the government will peacefully coexist after U.S. troops crate their weapons, fold their banners and leave.

Born into occupation, Sezdah is a man with a wary eye on what lies ahead. He and his friendsâ latest rap â a haunting five-minute cry for tolerance posted on YouTube â opens with aerial shots of the cityâs teeming markets and mosques. His message is to the Taliban fighters seeking to reimpose strict Islamic law that would leave little room for his art.

âIâm yearning for peace, for empathy, for a nation standing with my revolution,â he raps over a mournful melody. âSo many of us got martyred for what we have now.â

The names of the dead live in his voice: Ali, a friend killed with 34 others by gunmen who attacked Kabul University this month while Sezdah was in class. Another friend, 18-year-old Amir, who died two years ago when an Islamic State suicide bomber struck a nearby college prep center.

Nearly 6,000 Afghan civilians, young and old, urban and rural, were killed or wounded in the first nine months of the year, 30% fewer than in 2019, according to the United Nations. But that trend isnât likely to last.

A return of the Taliban, who ruled Kabul and much of the country between 1996 and 2001, has never seemed closer. Attacks and assassinations are spiking. Peace talks between the insurgents and the Afghan government appear stillborn. And U.S. troops, their numbers falling below 5,000 this month, are due to depart completely by May 2021 â never truly defeating what Washington spent trillions of dollars and nearly 2,400 American lives to crush.

Many young people are adamant about staying and fighting, hoping the Taliban â if it returns â cannot rule a capital that now allows girls into classrooms and a relatively free press. Many others are less sure. They are packing to leave.

âWhat will happen to our achievements?â says 16-year-old Khurshid Muhammadi, a player on the 10-year-old Afghan womenâs national soccer team. âWe may not be able to work and again have to wear head-to-toe burkas the Taliban once forced women to wear in public.â

The Taliban has acknowledged past shortcomings. Its leaders say they are not the same as before. Yet many young Afghans remain skeptical that militants who have chopped the hands off thieves, blown up ancient Buddha statues and given sanctuary to Osama bin Laden will be anything but cruel and extreme.

âFor the past 20 years, people have aspired to lives that are very different, but Taliban are cut off from this reality,â said Shaharzad Akbar, chairperson of Afghanistanâs Independent Human Rights Commission. âThey are very strict in their understanding of whatâs right and wrong, and they believe it is their God-given right to impose it on everyone else.â

While many â especially in urban centers â have seen progress in recent years, other lives have taken a turn for the worse.

Safiullah Sangari, 22, says his native village in Nangarhar provinceâs Shinwar district has tumbled into rubble. âU.S. airstrikes have destroyed most houses,â he said, leading him to take up arms four years ago when he joined the Taliban to fight the âforeign invaders.â

âIt was our struggle to fight them,â he said. âNow they [the U.S.] donât have a choice but to sit at the table with us. Everyone knows that we won this fight.â

Sangari grew up in the dun-colored hills of eastern Afghanistan, his village built from mud bricks, surrounded by farmland and cannabis fields. A child of conflict, he has seen little to make his life better, despite decades of international aid intended to extend Kabulâs government services into rural areas. His education ended after sixth grade.

âOf course foreign investment is necessary to bring the country forward,â he admitted, âbut it shouldnât be in the form of tanks and guns. Iâve only seen fighting. I havenât seen opportunities for education and business.â

Sangari receives no salary from the Taliban, but he is committed to helping them rule. His last operation took him to nearby Khogyani district, where he attacked an Afghan army outpost. He doesnât know if heâs ever killed anyone. âMaybe,â he said, shrugging. âSome of my bullets might have hit the soldiers.â

Living just a three-hour drive from the Afghan capital, Sangari, unmarried and devout, admitted that heâd never visited Kabul. But he shares one sentiment with his generation across the country: âEveryone wants peace,â he said. âWe donât want to keep fighting.â

Moscow and Washington are intertwined in a complex and bloody history in Afghanistan, with both suffering thousands of dead and wounded in conflicts lasting for years.

Soraya Shahidiâs life is vastly different from Sangariâs. But she has the same wish.

The 27-year-old single mother of a 9-year-old son is one of Kabulâs few female tattoo artists. She has had nearly 30 clients, men and women, since opening her business two years ago. Petite and fashionable, Shahidi grew fascinated with the art form after friends persuaded her to get a tattoo on her forearm.

The design â a dreamcatcher motif impaled by an arrow â had little meaning to her. It was the act of getting it that appealed to her boundary-testing instincts. A tiny silver stud in her pierced lower lip, she is the kind of woman who at once perplexes and infuriates the Taliban.

Born in Iran, where her parents moved in 1990 to escape Afghanistanâs civil war, she returned to Kabul with them in 2002, hoping it would be safer after the U.S. invasion. In the nearly two decades since, Shahidi has slowly built an untraditional life, divorcing an abusive husband in spite of the shame her parents feared it would bring on the family.

She took a class on tattooing in Iran, then another in Turkey in 2018, encouraged by her U.S.-educated brother, Ali. Tattoos became a side business after opening a beauty salon with her two sisters. Word of her services have spread on Instagram, and now she says she is recognized on the street.

But notoriety has brought harassment. Some men ask if she will tattoo the private parts of their bodies. She has been physically assaulted, she says, by men who say Islam forbids women in her profession. An Islamic cleric denounced her on Afghan television.

Shahidi would not bend. She and her family moved their salon to a larger compound nearby, painting âAngels Beauty Salonâ in gleaming gold English over the gated entrance. She is renovating a street-facing room to serve as a tattoo parlor, hoping to draw more customers.

But the looming exit â unless President-elect Joe Biden changes course â of American troops has forced Shahidi to contemplate what she will do if the Taliban returns to Kabul. In her apartment above the shop, her pale pet snake sits in a glass bowl on the shelf. It bit her once, and for that she has named it âPashm Riz,â a Dari phrase meaning something so frightful it makes oneâs hair fall out.

But even those with freedoms far outside Kabul fear the hard ways and strict scriptures of the Taliban.

Pakistan issues financial sanctions against the Taliban just as the militant group is in the midst of a U.S.-led peace process in Afghanistan.

Hafiza Faroke was born shortly after the 9/11 attacks and days before the United States stormed into her native Kandahar province in 2001. Her parents were on the run continually to escape airstrikes and fighting in the provinceâs outlying Panjwayi district, eventually settling in Kandaharâs city center.

The city was still dangerous for much of the last two decades, even with Afghan and foreign troops patrolling the streets. Girls like Hafiza could nonetheless attend school. Her parents pushed her to study hard, supporting her aspiration to one day attend university.

But after graduating from high school in 2018, Hafiza put her university ambitions on hold. Instead, she opened her own elementary school in her familyâs living room. Enrollment swelled so quickly that the 19-year-old director moved to a rented townhouse surrounded by compound walls. The Ministry of Education later put the 16 teachers on the government payroll.

The school now teaches over 400 students, most of them girls of conservative parents who prefer their children receive religious education, along with math, science and writing.

Yet Hafiza, sitting cross-legged on the floor in one of her schoolâs classrooms, wearing a light pink scarf, says even a school with religious instruction is a target.

âIf the Taliban returns,â she says, âit might mean women â literate and illiterate â are once again hidden behind closed doors.â

The cost to stay is too much for some.

Muhammad Haidar, a 22-year-old jewelry maker in Kabul, wants to leave for the United States or Canada, or almost anyplace where he can make a living selling his handmade silver earrings and lapis stone pendants.

Trained in his craft by a British-funded nongovernmental organization, he and his two partners made over $30,000 between 2016 and 2019 selling their jewelry, mostly to aid workers and diplomats in Kabul.

But with the COVID-19 pandemic, and many non-Afghans leaving the country, their one-room shop sees few customers.

Haidar has tried going to Gulbahar Center, a dank Kabul mall frequented by brokers who offer to procure visas. He paid $4,000 and handed over his passport in April to one of them promising a visa to Turkey. The deal fell apart when Turkey temporarily closed its consular services and canceled fights due to the pandemic.

A Canadian visa would cost $40,000, far more than he could pay, and it might be a fake anyway, says Haidar, dressed in a denim jacket and sneakers.

âI am very afraid that one day when I go to my work, I will die,â he says.

Tens of thousands have. Attacks and assassinations erupt regularly, often against young people striving to change their country.

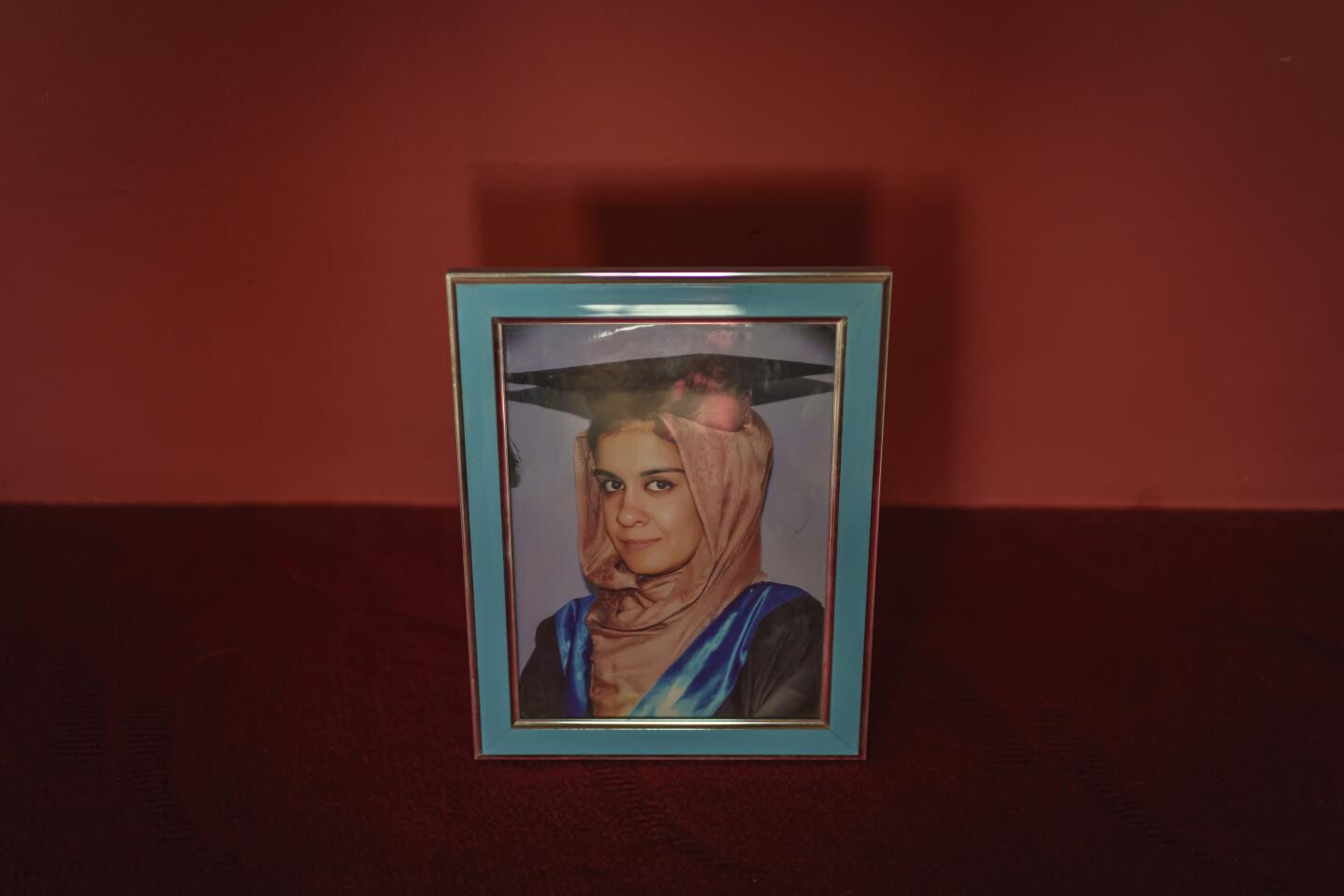

Fatima Khalil had just celebrated her 24th birthday in June when she was killed in Kabul by a bomb attached to her car.

She had grown up in the capital, returning with her family from a refugee camp in Pakistan shortly after the U.S. invasion. After finishing her degree at the American University of Central Asia in Kyrgyzstan, she had taken a job with Afghanistanâs Independent Human Rights Commission.

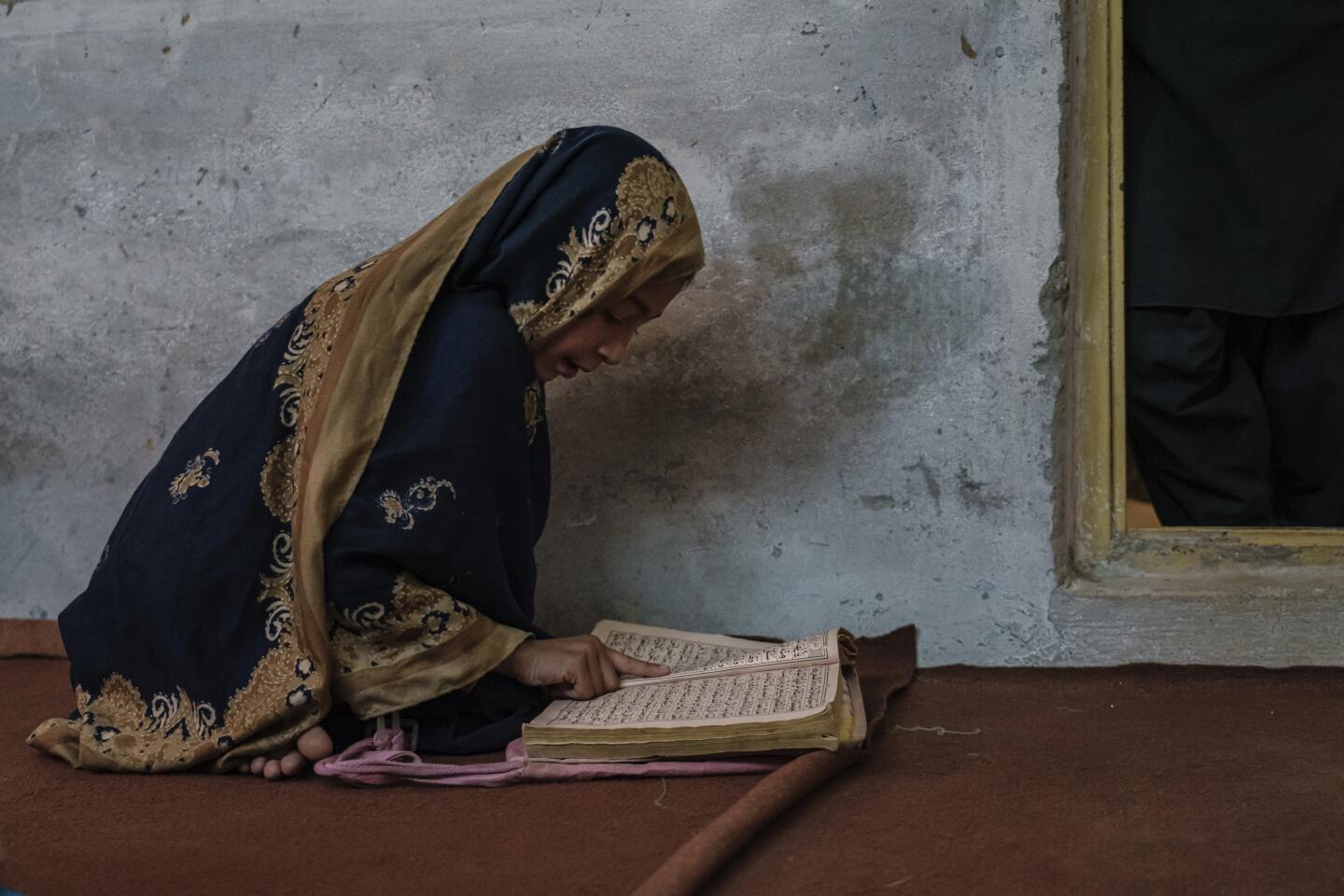

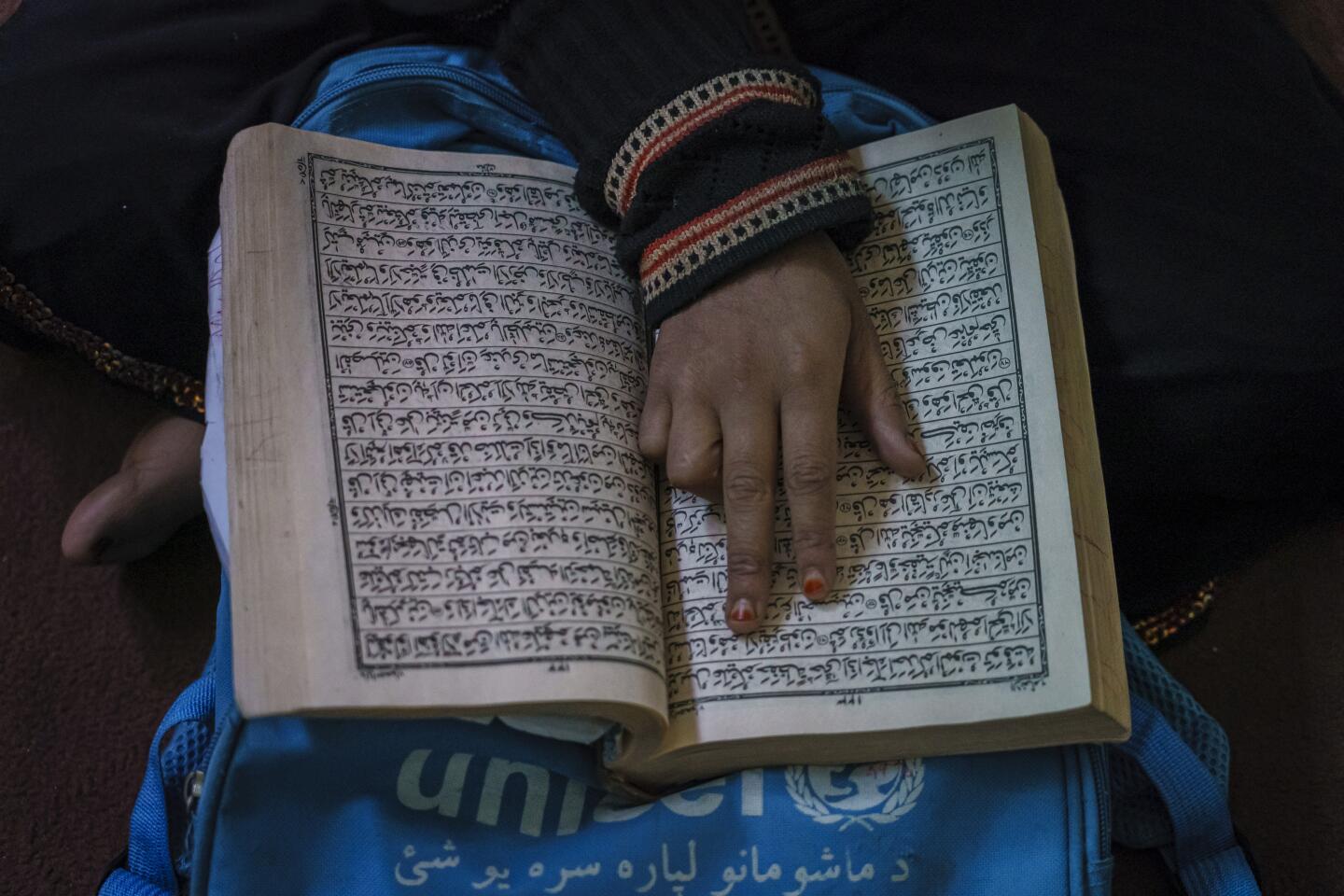

Her mother, Halima Sarwar, 62, sat quietly on what was once Fatimaâs bed in the familyâs Kabul apartment, wiping tears from her eyes with her headscarf. A graduation photo, propped between books and a bowl of chocolates, showed Fatima smiling in cap and gown, exposing a pair of pink sneakers as she crouched on the grass.

With her murder and no answers as to who killed Fatima, her familyâs hopefulness is fading.

âWho will bring change if people kill her generation?â her mother says, quietly adding one wish for the future: âDonât bring back the dark times.â

But some sense they are close.

Music echoed as dusk fell on a recent Friday in Jawad Sezdahâs studio on the other side of Kabul. He and his rapper friends crowded around a computer, laying down a new beat over a sampled melody from YouTube. They were connected to the larger world in ways their parents could never imagine.

Enveloped in smoke, Jawad was on his bare feet, swaying his arms to the rhythm, trying out words. Others joined in as the sound synced. They laughed and nodded in unison, finding something, then losing it. Someone opened the door to let the air clear.

The beat abruptly halted. The computer had crashed. Night had come.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.