Census numbers — more diverse, more urban — present a challenge to GOP

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Census figures showing that the U.S. got more diverse and more urban — and did so at a faster rate than expected over the past decade — have buoyed the hopes of Democrats as the two parties head into the once-a-decade battle over drawing new lines for congressional and legislative districts.

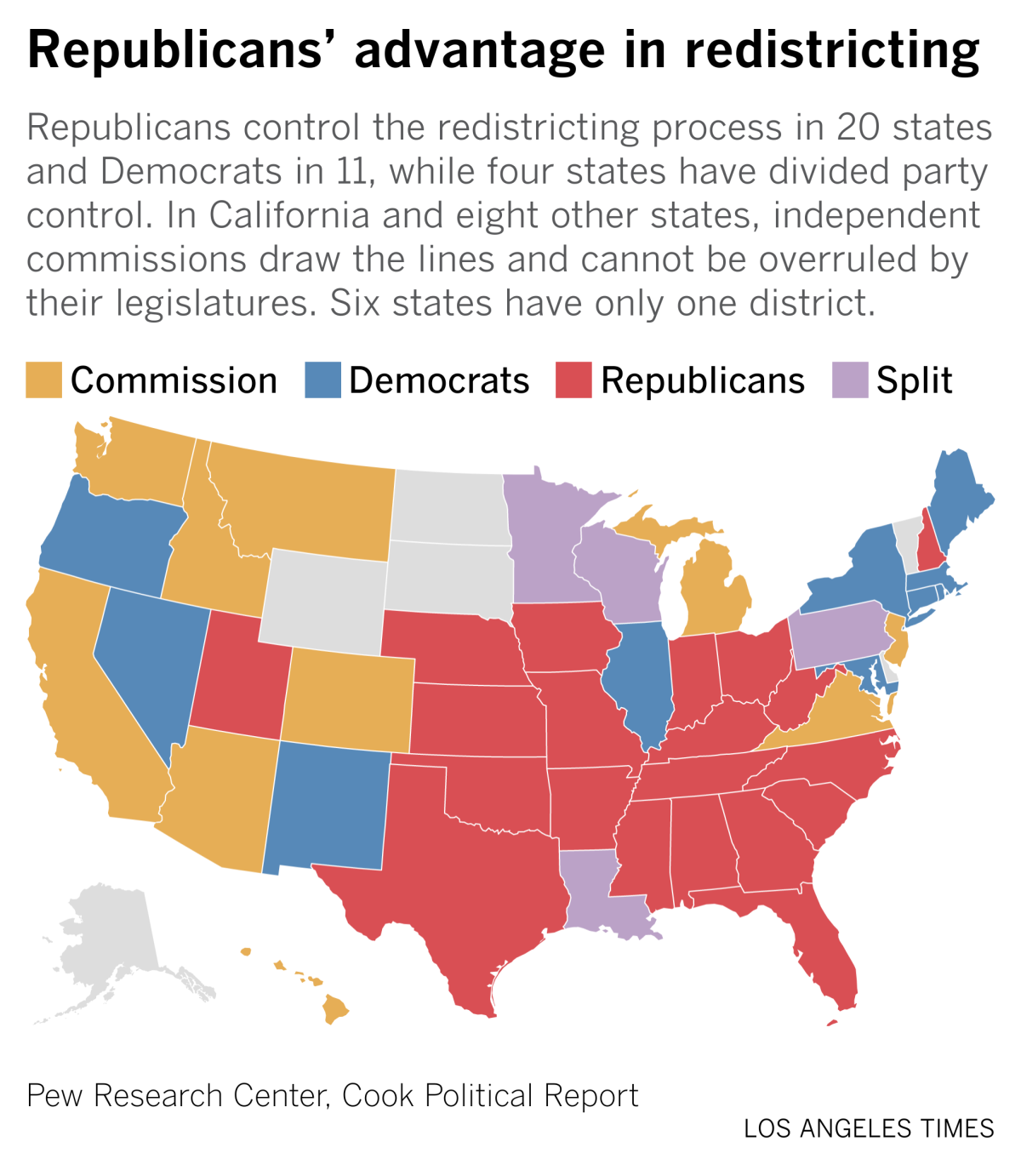

Republicans still have the upper hand for two reasons: They control the process in more states than Democrats do, and their voters are more spread out, which gives them an advantage in the U.S. system of districts based on geography. But Thursday’s data release, which allowed the redistricting process to formally start, highlighted the limits of the GOP’s strategy of relying on a white, rural base in a country that is increasingly nonwhite and urban.

For the first time in U.S. history, the number of people identifying themselves as white on the census, 223.6 million, dropped compared with 10 years earlier. Non-Latino, white Americans dropped below 60% of the population for the first time, to just short of 58%. The nation’s Latino population rose to 62.1 million, or just under 19% of the total, and the number of Americans identifying as Black, Asian or multiracial also increased.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Those milestones have long been expected — they result from the aging of the country’s white population and a declining birthrate, as well as the big increase in the number of people who identify as multiracial. Nonetheless, the reality of the new numbers will likely amp up the volume of fear-mongering rhetoric on the right, where warnings of “demographic replacement” have become staples in recent years, pushed by white nationalists and conservative media figures.

For everyone else, the numbers highlight the reality of a changing country.

“The U.S. population is much more multiracial and much more racially and ethnically diverse than we measured in the past,” as Nicholas Jones, the Census Bureau’s director of race and ethnicity research, said at a news conference releasing the new numbers.

The GOP advantage and its limits

Despite the country’s demographic changes, Republicans have strong hopes of capturing a majority of the House after the 2022 election. Democrats think that’s likely, too; much of their legislative strategy starts with the assumption that control of both houses of Congress won’t stay in their hands for long.

Redistricting — the redrawing of congressional boundaries to roughly equalize district populations — accounts for a big part of the Republican optimism.

The vast majority of the country’s 435 congressional districts aren’t competitive no matter who draws the lines: Republicans aren’t going to win in Los Angeles any time soon, just as Democrats won’t carry deep-red parts of Arizona.

But redistricting is a battle won on the margins. Republicans need only five more seats to regain the House majority they lost in 2018. Their edge in redistricting could, by itself, provide that.

That edge in the process stems, in part, from an accident of history: In 2010, amid the tea party backlash against President Obama, the GOP won a significant majority of state legislatures. That just happened to be the election right before the last round of redistricting, perfect timing for the GOP, which was able to entrench its power by gerrymandering districts.

Many of those gerrymanders proved durable. In Wisconsin, Michigan and North Carolina, for example, Democrats won all three of the most recent elections for governor. But the GOP has kept control of all six legislative chambers in those three states because of favorable legislative boundaries.

Democrats gerrymander, too, of course — Maryland provides an example — but they’ve had many fewer opportunities.

The nonpartisan Cook Political Report counts 187 congressional districts where Republicans will have full control of the process this time around, compared with 75 that Democrats will control. Most of the rest will be drawn by independent commissions, such as the one that draws the lines in California, although a few states have split control. That’s a less lopsided GOP advantage than 10 years ago, but still a formidable one.

Whichever body draws the lines, however, they’ll be dealing with demographic realities that limit GOP options.

“While Republicans may hang on to some of their base in Congress in the short run through selective gerrymandering, broad demographic forces, as seen with the new census data, clearly favor Democrats,” said Brookings Institution demographics expert William Frey.

Republicans have their strongest support in rural areas, for example, but the growth in the U.S. population over the last decade came in big cities and their suburbs. Thursday’s data revealed that trend was even sharper than previous estimates had suggested.

All 10 of the nation’s largest cities gained population, paced by New York, which grew almost 8% over the decade. (Los Angeles grew by 2.8%.) At the same time, the nation’s rural population shrank. Just over half of U.S. counties lost population, with those losses concentrated in counties with populations less than 50,000.

“The country’s population is increasingly metropolitan,” the Census bureau’s Marc Perry said Thursday.

The impact can easily be seen in a place like Maine, which has only two districts — one exclusively rural, which former President Trump narrowly carried in 2020, and the other that contains the state’s metropolitan areas, which President Biden won handily. The state’s population gain came exclusively in the blue district. When the state legislature redraws the lines to equalize populations, the rural, 2nd district will almost certainly become somewhat more Democratic.

At the other end of the scale, New York City’s rapid population increase means it will gain sway in the state’s politics.

New York is the state Republicans worry about most this time around. A decade ago, they still controlled one house of the state legislature, forcing a compromise that preserved Republican-majority districts. They no longer have that buffer, and Democrats almost certainly will try to wipe out at least some of the current eight GOP districts as the state’s overall delegation goes from 27 down to 26. Dave Wasserman, the redistricting expert at the Cook Political Report, estimates that the mostly Republican population of Upstate New York is now enough to support only nine districts, down from 10 a decade ago.

Depending on what the California’s independent redistricting commission does, the state also could be a significant battleground. Democrats picked up seven California seats in 2018, but Republicans regained four in 2020.

Many of the most consequential decisions, however, will come in Republican-majority states where population growth came almost entirely from people of color. In Texas, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina, for example, Republicans will have to decide whether to accommodate racial and ethnic change or continue to fight it in the legislatures and in the inevitable court challenges that will come once the lines are drawn.

In Georgia, for example, the growth of the state’s Black, Latino and Asian voter populations, especially in the Atlanta suburbs, provided the key that allowed Biden to narrowly carry the state last year and Sens. Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock to win special elections in January. The Census shows that the non-Latino, white population of the state has dropped to 50.1%.

A decade ago, Georgia Republicans created a congressional map that gave them a 10-4 majority in the state’s delegation. By decade’s end, the rapid growth of the Black voter population in metro Atlanta helped flip two of those districts, leaving the split at 8-6. Republicans will try to redraw the lines to win back at least one of those districts, but the state’s rapid demographic change probably will frustrate their hopes of regaining both.

In several other Republican majority states, census figures highlight the question of what approach the GOP will take toward the growing Latino population. That’s especially true in Texas, where Latinos now almost equal non-Latino whites as a share of the population, but lag significantly behind in the number of voters.

In the last redistricting fight, courts found that Texas Republicans did everything they could to avoid creating Latino-majority districts. But Trump did better than Democrats had expected among Latino voters in Texas in 2020.

Some Republican strategists believe that result marked a trend that will allow their party to form a populist coalition of white and Latino working-class voters. A lot of white Republican voters, however, remain uncomfortable with any increase in Latino political power, an unease that purveyors of theories about demographic replacement prey upon.

Whether the GOP will take the risk of trying to forge a multicultural course or continue down the track toward becoming an expressly white party is a huge question for the future of American politics. The Census figures make clear that the party has only limited time to make up its mind.

Can Biden rescue Newsom?

With polls showing that Democratic apathy poses a significant risk for California Gov. Gavin Newsom in next month’s recall election, Biden and other senior members of his administration, including Vice President Kamala Harris, are preparing a major support operation, Mark Barabak reported.

The effort puts the national party strongly in Newsom’s corner, in a way that both parties steered away from during the state’s last recall election, in 2003.

Newsom has been urging Democrats to vote only on the first question on the ballot — whether he should stay in office — and skip the second question, which asks who should replace him if he loses. George Skelton says that Democrats should ignore that advice.

Newsom won a major victory in court this week as the California Supreme Court upheld his power to issue sweeping executive orders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maura Dolan reported that the state’s highest court declined to review a lower-court decision that said California’s Emergency Services Act of 1970 gives the governor broad powers during the pandemic.

For all the latest on the recall election and other key issues in the state, sign up for our new weekly California Politics newsletter, featuring the best of The Times’ state politics reporting and the latest action in Sacramento.

Our daily news podcast

If you’re a fan of this newsletter, you’ll probably love our new daily podcast, “The Times,” hosted by columnist Gustavo Arellano, along with reporters from across our newsroom. Every weekday, it takes you beyond the headlines. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts and follow on Spotify.

Rapid collapse in Afghanistan

In April, when Biden announced that U.S. troops would leave Afghanistan after 20 years of inconclusive fighting, aides said they hoped the Afghan government would be able to hold off a Taliban offensive. The opposite has happened; Afghan security forces are rapidly crumbling as Taliban forces take one provincial capital after another.

On Thursday, Tracy Wilkinson reported, the administration announced it was pulling most U.S. Embassy personnel out of Kabul and would send several thousand U.S. troops to help with the partial evacuation.

There’s no sign that Biden is contemplating a change of course, however. So far, there’s also no sign that he’s paid a political price for presiding over the collapse of the U.S.-backed Afghan government. A sweeping Taliban victory might change that, but might not. Most Americans seem to have long ago written off the Afghan war as a mistake.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Will the green economy yield good jobs?

Biden predicts his plans to spend billions of dollars to foster renewable energy production will produce hundreds of thousands of good-paying, blue-collar union jobs. But as Sammy Roth and Chris Megerian reported, it’s not a sure bet. The transition away from fossil fuels could cause upheaval for some workers even as it produces new opportunity for others.

Much of that money is contained in the $3.5-trillion budget package that Biden and Democratic leaders are pushing, as well as the roughly $1.2-trillion bipartisan infrastructure deal that the Senate passed on Tuesday. Sarah Wire looked at what’s ahead as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi tries to maneuver both of those bills through the House.

Nomination blues

The Senate went on recess for the rest of this month with a long list of Biden’s nominees, especially for diplomatic posts, still hanging. As Wilkinson reported, Republican senators have stalled the nominations to protest administration policies they disagree with, frustrating Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken and other officials.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.