Essential Politics: A $400-million Newsom recall election?

- Share via

This is the April 26, 2021, edition of the Essential Politics newsletter. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox three times a week.

It’s well known that elections have consequences. They also have price tags.

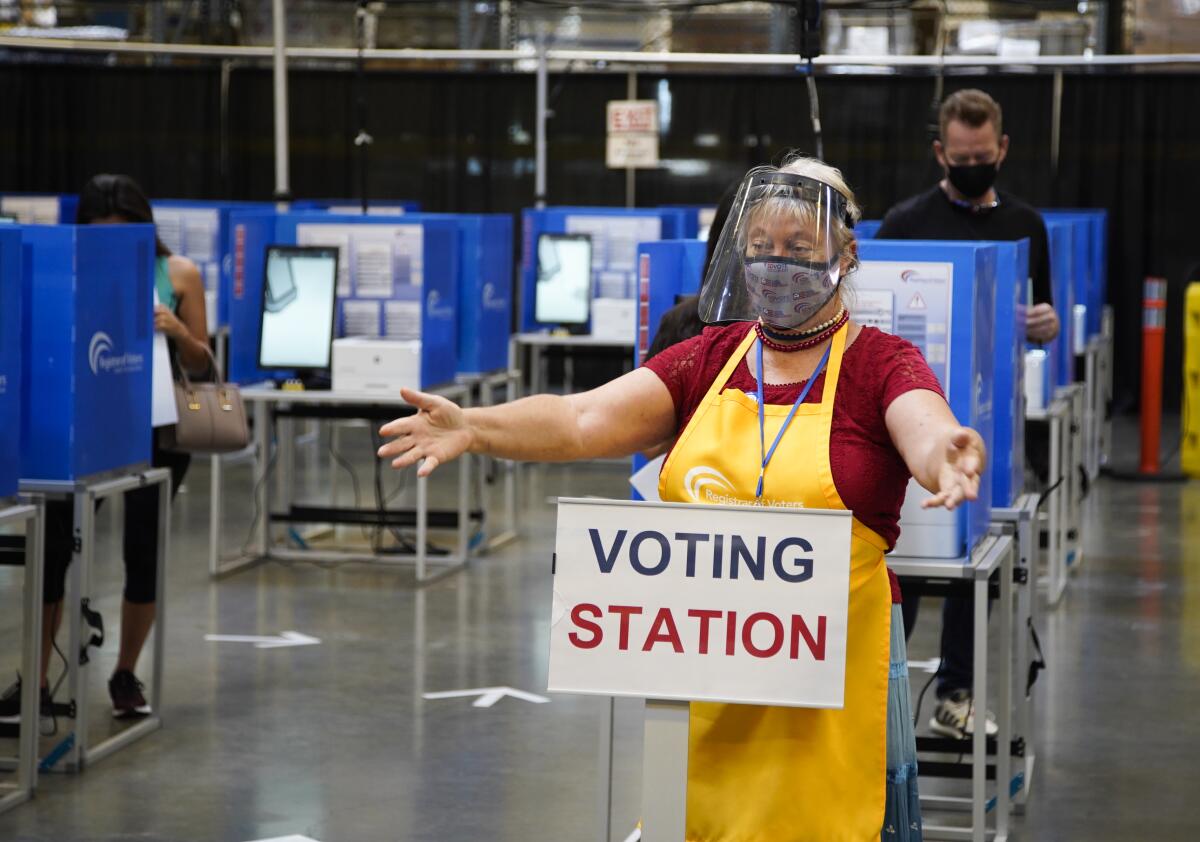

With signs pointing to a special election this fall at which voters could remove Gov. Gavin Newsom from office, local officials from across California believe the cost of conducting the election could run as high as $400 million.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The estimate is four to five times higher than rough guesses bandied about in recent months and is equal to a cost of about $18 per registered voter — more than double what local elections officials say was spent on California elections in 2018.

It’s a price they say counties, which are struggling to cover pandemic-related costs for health and human services programs, will need the state to cover.

“There is an urgency to this,” said Donna Johnston, the registrar of voters in Sutter County and president of the California Assn. of Clerks and Elected Officials.

Who will pay for the recall?

Johnston’s group bases its $400-million estimate on a preliminary tally of costs from the November 2020 election, for which every registered voter was mailed a ballot and in-person voting was subject to strict rules designed to minimize the risk of coronavirus infections.

The recall election will be conducted in a similar fashion. Already, state officials have extended the mailing of ballots to all voters for any 2021 special elections.

With expenses reported by 33 of California’s 58 counties, the clerks association’s tally for last November stands at $292 million; final numbers could make it the most expensive election in state history. It was also an election subsidized by federal coronavirus relief funds. In some small counties, the money covered the majority of election expenses.

There are no expectations for that kind of help to conduct a gubernatorial recall.

“It would force some very hard decisions with only county resources,” Johnston said.

A little-noticed provision in a 2017 California law that revised recall election rules seems to indicate that the state will pick up the tab for “reasonably necessary” costs but also notes that there must be funds “designated for that purpose.”

A spokesman for Newsom declined to say whether the governor supports setting aside money in the new state budget for a recall election. The governor’s campaign spokesman, Dan Newman, said Californians would rather spend the money on helping schools and small businesses affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The leaders of the two legislative houses, asked about support for the state paying the cost of the election, instead criticized the recall’s proponents.

“Neither the state nor the counties should be stuck footing the bill for such an unnecessary election,” said Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood).

“This is a very expensive partisan Republican ploy, and as usual they are leaving the taxpayers holding the bag, any way you look at it,” Senate President Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) said in an email to The Times.

Randy Economy, a spokesman for the Newsom recall campaign, said some costs — notably the requirement to mail every registered voter a ballot — could have been avoided if officials would allow a “traditional” election. He said the governor, through his actions, is the one who bears responsibility.

“You can’t put a price on democracy,” Economy said. “The only reason we’re in this position is Gavin Newsom.”

California’s long list of election IOUs

The looming question of who will pay to conduct the recall is a stark reminder of how California elections have been chronically underfunded for years.

“While the state reaps regular benefits from county elections administration, it only sporadically provides funding to counties for election activities,” the independent Legislative Analyst’s Office wrote in a 2017 report.

The report estimated the state’s total IOU to counties for past election mandates at the time at $71 million and said it would grow by about $30 million every general election year without legislative action. Johnston, the president of the clerks association, said some estimates now put the state’s election IOU at $160 million.

Voters may not realize the potential consequences. In a 2017 column, I noted that California law allows counties to simply stop offering some of these election services if the state doesn’t cough up enough cash: “They could refuse to provide absentee ballots to anyone who wants one. Or perhaps even more provocative in the current election-integrity climate, they could refuse to use long-standing legal rules when asked to verify a voter’s signature on a provisional ballot. No money, no mandated services.”

As new election rules take effect, counties will keep making the case for the state to pay its fair share. A new law allowing voter registration up to, and including, election day didn’t come with clear funding for locals — a decision challenged in December by San Diego County.

One thing we know for sure is that the state has the money. Already, there are estimates of a massive tax windfall and discretionary revenue in the state budget totaling as high as $20 billion through the summer of 2022.

“The best way for the state to show the counties some love is to give them the money,” said Kim Alexander, president of the nonpartisan California Voter Foundation.

Waiting for the recall signature tally

In a surprise to local elections officials and political watchers, last week ended with no report from Secretary of State Shirley Weber on the number of recall petition signatures that had been submitted by the counties byApril 19. An announcement could come as soon as Monday.

Weber’s office is responsible for collecting those reports from the counties and then conducting any final review, as needed, to make sure the numbers add up.

A spokesman for the secretary did not respond Friday to inquiries about the report’s timing. Based on the number of voter signatures that had been validated last month and preliminary reports from a few counties, the tally is expected to confirm what even Newsom has already conceded: He will face a recall election later this year.

Counties must finalize all recall petition reviews by Thursday. Once Weber notifies elections officials of the results, the clock starts on a series of other recall election preparations.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

‘I’m in,’ says Caitlyn Jenner

California’s 2003 gubernatorial recall attracted several celebrities, so perhaps it’s not surprising that the 2021 edition is poised to reflect a blend of politics and Hollywood, courtesy of Caitlyn Jenner.

Last week, the reality TV star and former Olympic champion announced her intention to run in the recall election to serve the year remaining on Newsom’s term in office, should voters oust him.

“I am a proven winner and the only outsider who can put an end to Gavin Newsom’s disastrous time as governor,” the 71-year-old Jenner, a Republican, wrote on Twitter.

The emergence of Jenner, bringing her blend of activism on transgender issues and onetime support for former President Donald Trump, made national headlines. Newsom’s political team sent out multiple fundraising emails in the hours after the news broke. On Saturday, the campaign warned donors that Jenner is part of a GOP effort to “install a Trump acolyte into power” in California.

Some pundits compared Jenner’s candidacy to that of Arnold Schwarzenegger, who handily won the 2003 election in which voters recalled Gov. Gray Davis. But for those of us who covered that election, the comparison has its limits. Most notably, Schwarzenegger had long been mulling a run for governor — one for which he had laid the groundwork by successfully championing a 2002 statewide ballot measure providing funds for afterschool programs.

On the campaign trail, Schwarzenegger certainly capitalized on his iconic image but did so to attract attention to his serious campaign platform. He eventually won the backing of California Republican leaders and cemented his support among the GOP’s base.

“What credentials are there?” Don Sipple, a political consultant who produced advertising for Schwarzenegger’s 2003 campaign, said of Jenner. “What’s the groundwork that’s been laid in the public policy arena to suggest she would be a plausible candidate or a plausible governor?”

The early hours of Jenner’s candidacy were turbulent. Her decision was quickly criticized by one of California’s largest LGBTQ rights groups and by trans activists around the country. And in a tweet posted Saturday, she suggested that district attorneys in California are either chosen or answer to Newsom — neither scenario, however, is true.

National lightning round

— As his presidency reaches its 100th day this week, it’s clear that President Biden has chosen to govern as a progressive, significantly to the left of his three Democratic predecessors on the issue of government’s role in society.

— Biden on Saturday formally recognized as genocide the killing of more than 1 million Armenians starting in 1915, a label long used by historians but resisted by U.S. presidents to avoid angering Turkey, an important ally.

— Months after former Trump’s election defeat, legislative Republicans in Arizona are challenging the outcome as they embark on an unprecedented effort to audit the results.

Today’s essential California politics

— Newsom on Friday took action to ban new permits for hydraulic fracturing starting in 2024, a reversal from previous statements that he lacked the executive authority to do so.

— The Legislature confirmed Democratic Assemblyman Rob Bonta as California attorney general on Thursday. He told his former colleagues that he would hold law enforcement accountable for excessive force and other misconduct.

— A federal appeals court decided Friday that criminal defendants were not robbed of their right to speedy trials or forced unconstitutionally to remain behind bars because the COVID-19 pandemic delayed their trials.

— Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti’s spending plan for the 2021-22 fiscal year proposes a slight increase for the LAPD, disappointing advocates who want those funds used for social services.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.