Column: Vin Scully: Voice of the Dodgers, soundtrack to a California childhood

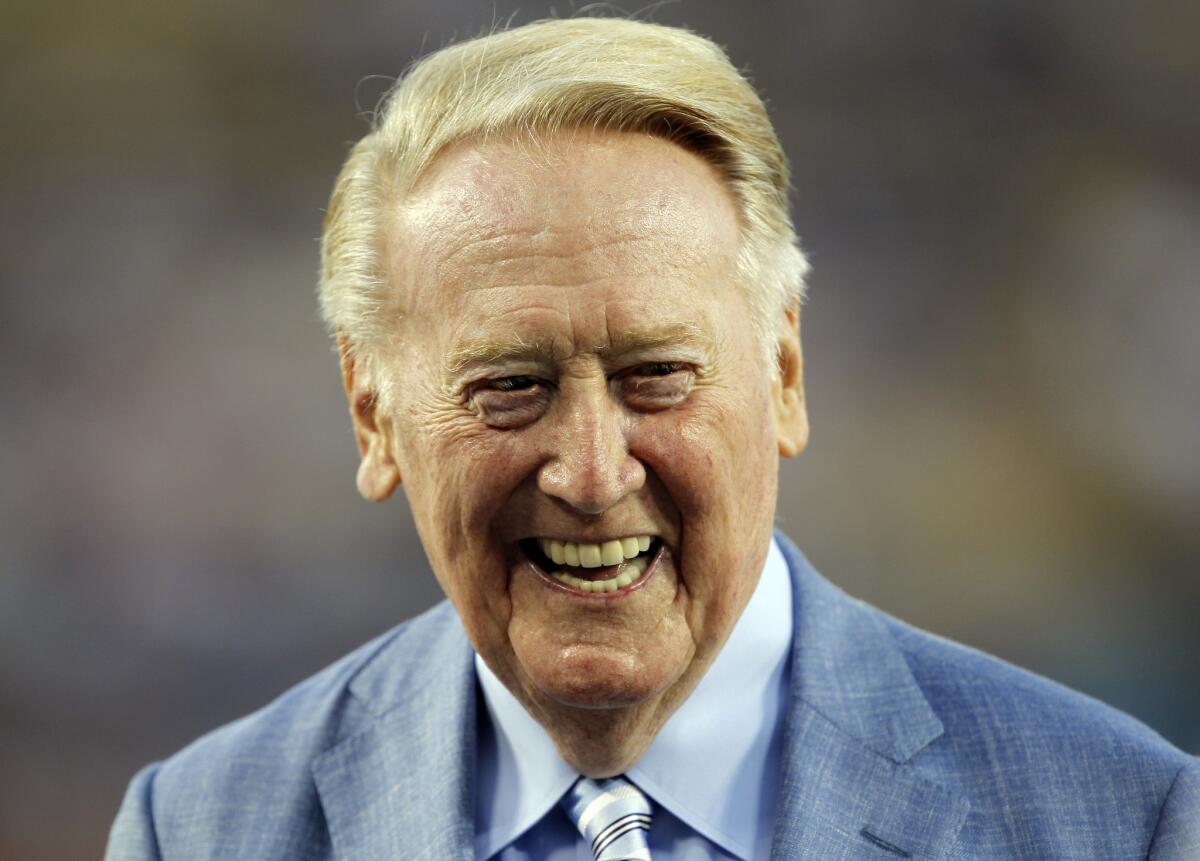

Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully is honored before a baseball game. Scully was given a Guinness World Records certificate for the longest career as a sports broadcaster for a single team.

Usually, I write about politics. Today, not as much.

Today is about Vin Scully, the poetic voice of the Dodgers, newly sidelined for the offseason by surgery. Temporarily, if prayers are heard.

Los Angeles erects giant edifices to symbolize this disparate place, to create a sense of community for a centerless amalgam of suburbs filled with people who may know nothing about the lives of the people next door. But more than the shiny buildings put up on Bunker Hill lately, Vin Scully is the real connective tissue, the greatest Los Angeles edifice.

For those of us raised in Southern California, he is also like the ticking clock--always there, dependable enough to set your life to.

I was raised in Long Beach, only 29 miles down the road from downtown Los Angeles but a town that then had a significant chip on its shoulder about the behemoth to the northeast. This played out in odd ways. Until the morning I started work at the Los Angeles Times as a junior in college, I had never seen its downtown building, nor the grand City Hall across the street, nor the glorious Public Library a few blocks away. They were of Los Angeles, and we weren’t.

The sole exceptions were sporting venues. We hung out in season seats in UCLA’s basketball arena, Pauley Pavilion, in the second to the last row up high behind the team‎ benches. Close enough to see Coach John Wooden, another Los Angeles edifice, wrap his papers into a tube he could point for emphasis rather than lose his mild demeanor to a bellow.

My father, a former UCLA baseball pitcher, wanted never to lose touch with that elemental part of him. He could see himself in the athletes on the court.

My dad coached his four kids in baseball from the time we could walk. I threw left—inept at using the favored hand--but was taught to bat right, probably for his ease. I got to play in the boys’ park leagues, and no one raised a constitutional stink.

At school the fourth grade teacher‎, a nun named Sister Josephine Mary, played left field in our games, catching not with a glove but by holding up a few of the voluminous layers of her floor-length habit. And when the Dodgers made the World Series, the hard-nosed Catholic school teachers would roll portable black and white TVs into the classrooms, so we could watch the games.

For reasons I don’t know, the Dodgers from the very beginning connected us to baseball more than the UCLA team on which my dad had played. Maybe it was the pull of professional sports, a game my father would have loved to play had my arrival not stopped him in semi-pro.

So we trudged one day, in a drenching rain, up to a ledge in disdained Los Angeles to look into a giant pit. That’s Chavez Ravine, my dad said reverently. That’s where they’re building‎ Dodger Stadium.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

After it was built we had the run of the place. At some point, my dad’s job meant a share in season tickets, first base line. We scarfed down Dodger dogs and frozen chocolate malts fast, the better to catch any foul ball headed our way. Alas, the angle was mostly wrong.

The rules then gave season ticket holders twice the number of playoffs and series tickets as regular seats, meaning eight additional tickets besides the four behind first base.

The two oldest kids won the rights to the ‘60s series games. Off we trotted to the newly acquired seats, on the top deck, third base side, hundreds of feet up and across from where he sat. I was 9 and my brother was 7, if I remember right, when we first clambered up, snack money and gloves in hand, hoping an opponent would shank a Koufax or Drysdale pitch into our willing arms. It didn’t happen there either.

Still, we walked the stadium’s byways with the swagger of veterans.

You heard Vin Scully at the stadium, of course, by transistor radio. Row after row, fans would hold them to their ears to catch his radio broadcast, him talking to you, right to you, right to your awed ear.

The summer I turned 9 we listened from our backyard as he called a game from Candlestick Park, home of the scorned San Francisco Giants. Dodger catcher John Roseboro challenged Giants pitcher Juan Marichal for beaning two Dodger teammates. Marichal retaliated by cracking Roseboro on the head with his bat, opening a wound that would send blood running down Roseboro’s uniform.

We were aghast at the sudden violence. I remember staring at the transistor on the step, the cool of the concrete as we sat next to it, the light breeze‎. But Vin smoothed things out--cognizant, he said later, of the kids listening in.

If this is to be a little bit about politics, let’s say that it doesn’t appear lately that many politicians are cognizant of the kids, or of anyone else, as they bluster on. Maybe, in his hopefully temporary departure, Vin has left lessons for them, and lessons for all of us.

Be there, consistently: 66 years for him, so far. Make it not about you but everyone else: The stories he tells are not about his accolades but about other people, the legends and carny characters who inhabit baseball. Care, in an obvious and meaningful way, about the people you’re talking to.‎ Be the connective tissue that he is.

I was last at Dodger Stadium about 10 years ago, the season after my father died. It was August, again. We’d gotten tickets in the sunny part‎ of the stadium, forgetting how hot it would be.

We could hear Vin Scully through other people’s radios, a good thing as the transistor had long since died. The kids brought their gloves. No wayward foul balls came our way. And as before, that barely mattered.

For politics, go to www.latimes.com/decker and www.latimes.com/politics.

MORE ON VIN SCULLY

Dodgers’ postseason will be missing voice of Vin Scully, L.A.’s most-treasured star

Vin Scully to miss postseason after undergoing medical procedure

Dodgers Dugout: Vin Scully announcement puts spotlight on TV situation

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.