California governorâs race is likely to be decided in Los Angeles County

For the hopefuls in Californiaâs race for governor, the sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles County is as mesmerizing as the blanket of lights that glistens every night from the San Gabriel Mountains to the Long Beach coast.

The election will be decided here, where 1 in 4 of the stateâs voters live. Itâs diverse, sprawling, expensive to advertise in and voters often donât show up, especially compared with the Bay Area. Thatâs why anyone hoping to topple Democratic Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom has to win the county.

For two hometown Democratic candidates especially â former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and state Treasurer John Chiang of Torrance â doing well in L.A. County is essential. Yet this overwhelmingly Democratic stronghold continually bedevils even the most adept campaigns.

More than 180 languages are spoken here, where 5.2 million voters live, outnumbering the electorate in most states. A plurality of the county is Latino â 47.5 percent â and huge ethnic enclaves abound: Armenian Americans in Glendale, Chinese Americans in Monterey Park; and Filipino Americans in West Covina. The city of Los Angeles has the second largest population of Native Americans in the U.S.

Airing an effective television ad campaign â the only realistic way to reach voters from Palos Verdes to Palmdale and Pacific Palisades to Pomona â can cost $2 million a week.

All about the money in the governor's race »

Harnessing the countyâs political power base is tricky, since itâs a mishmash of entrenched public employee unions, Westside wealth, Latino-led political bulwarks and grass-roots organizations, Hollywood glitterati and corporate titans.

âI donât see a path to victory unless Villaraigosa or Chiang can dominate in Los Angeles,â said Democratic political consultant Rose Kapolczynski, who served as former Sen. Barbara Boxerâs chief campaign adviser.

Newsom, a former two-term San Francisco mayor, is expected to receive a warm embrace from voters in the Bay Area, where turnout is historically higher than L.A. County, especially in non-presidential years. Combined with his aggressive courtship of Californiaâs liberals, who mostly reside along the affluent California coast, the Bay Area vote gives Newsom a considerable advantage and helps explain his front-runner status.

The race in Los Angeles County itself is tighter. The USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times poll conducted in late October and early November found Villaraigosa and Newsom neck and neck among likely voters in the county, with both favored by approximately 27% of the electorate. Chiang landed in a distant third with 15%. In the Bay Area, Newsom was backed by 62% of voters compared to 12% for Chiang and 7% for Villaraigosa.

In a December UC Berkeley Institute of Government Studies poll, Villaraigosa led Newsom in L.A. County 31% to 20%, with Chiang at just 6%. Newsom still dominated in the Bay Area, with 55% of likely voter support and the others in single digits.

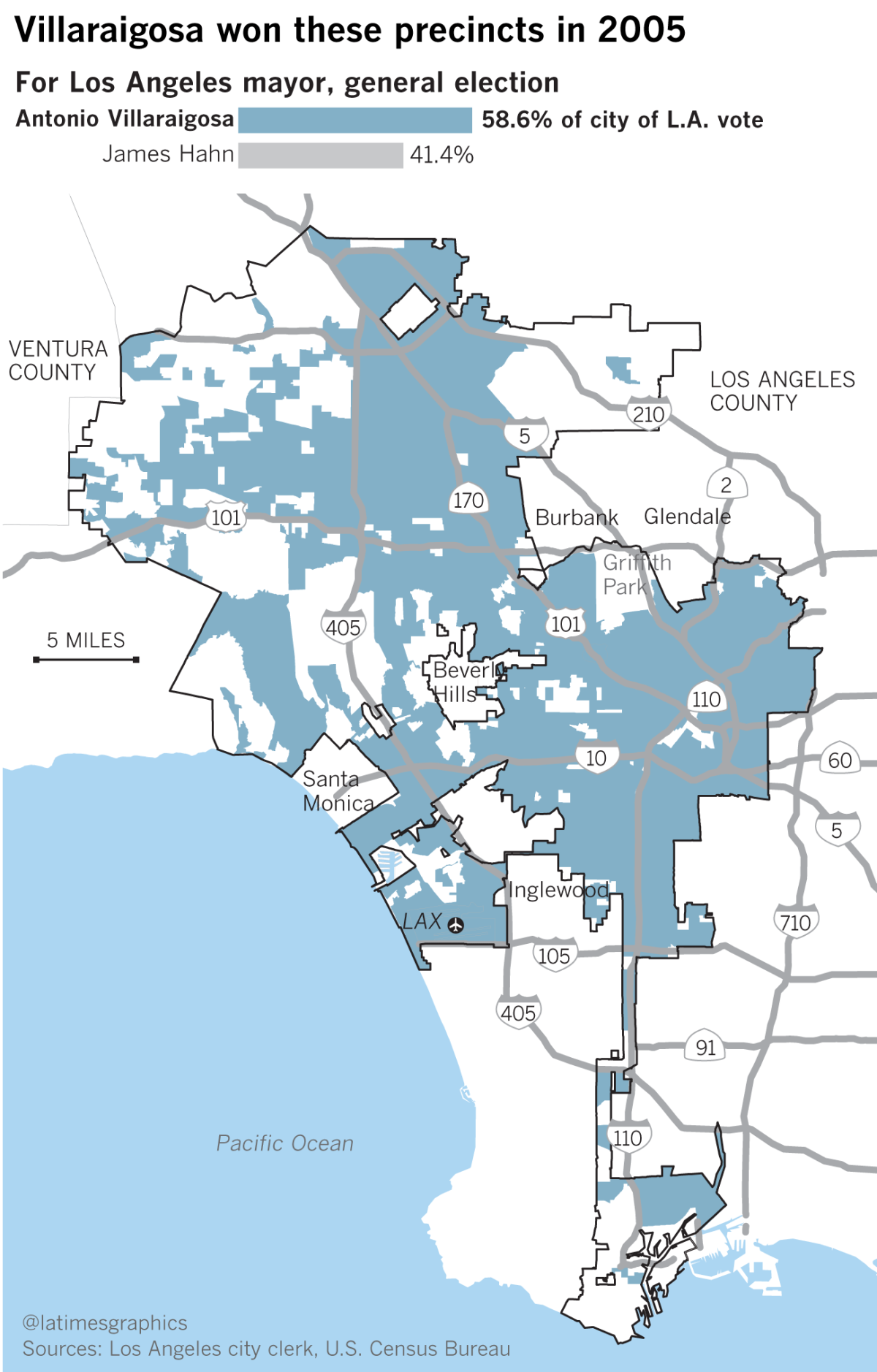

Villaraigosa has some built-in advantages. He was twice elected mayor of Los Angeles, Californiaâs largest city. Villaraigosa lost to Jim Hahn in the 2001 race for mayor of Los Angeles, but unseated Hahn four years later by cobbling together a patchwork of support, stealing from Hahnâs previous voting base in South L.A., the Westside and the central San Fernando Valley.

The question is whether Villaraigosa, who has been out of office since 2013, has the magic to pull that off again. A second-place finish in the June primary would be good enough since under Californiaâs âtop-twoâ primary system, the two candidates who receive the most votes advance to the November election regardless of their political party.

Polls show Villaraigosa still has a strong grip on a major slice of the electorate â Latinos. Roughly 40 percent of likely Latino voters statewide back him, double that of any other candidate, according to multiple polls. Approximately a third of Californiaâs Latino registered voters live in L.A. County.

Latino turnout is strongest in presidential election years. In L.A. County, the electorate in an off-year primary election tends to be older and less diverse. In the 2014 primary, voter turnout statewide was 25 percent â and just 17 percent in L.A. County. Among Latinos, it was 10%, said Mindy Romero, director of the California Civic Engagement Project at UC Davis.

Statewide turnout in 2016 among Latinos was about 50%, probably driven by opposition to then-candidate Donald Trumpâs anti-immigrant rhetoric. Should that energy linger into June, Villaraigosa might be the main beneficiary.

Chiangâs biggest problem is obscurity. Though heâs from the South Bay and has been elected to statewide office three times â twice as controller and once as treasurer â close to a third of likely voters in L.A. County have never heard of him, a Public Policy Institute of California poll found.

Parke Skelton, who recently stepped down as Chiangâs campaign advisor, said in December that the treasurer has developed a loyal following among Californiaâs growing pool of Asian American voters. Skelton predicted the group could make up 8% of the California primary electorate. Chiang already has proven to have a substantial edge when it comes to winning over Asian American political donors across the political spectrum.

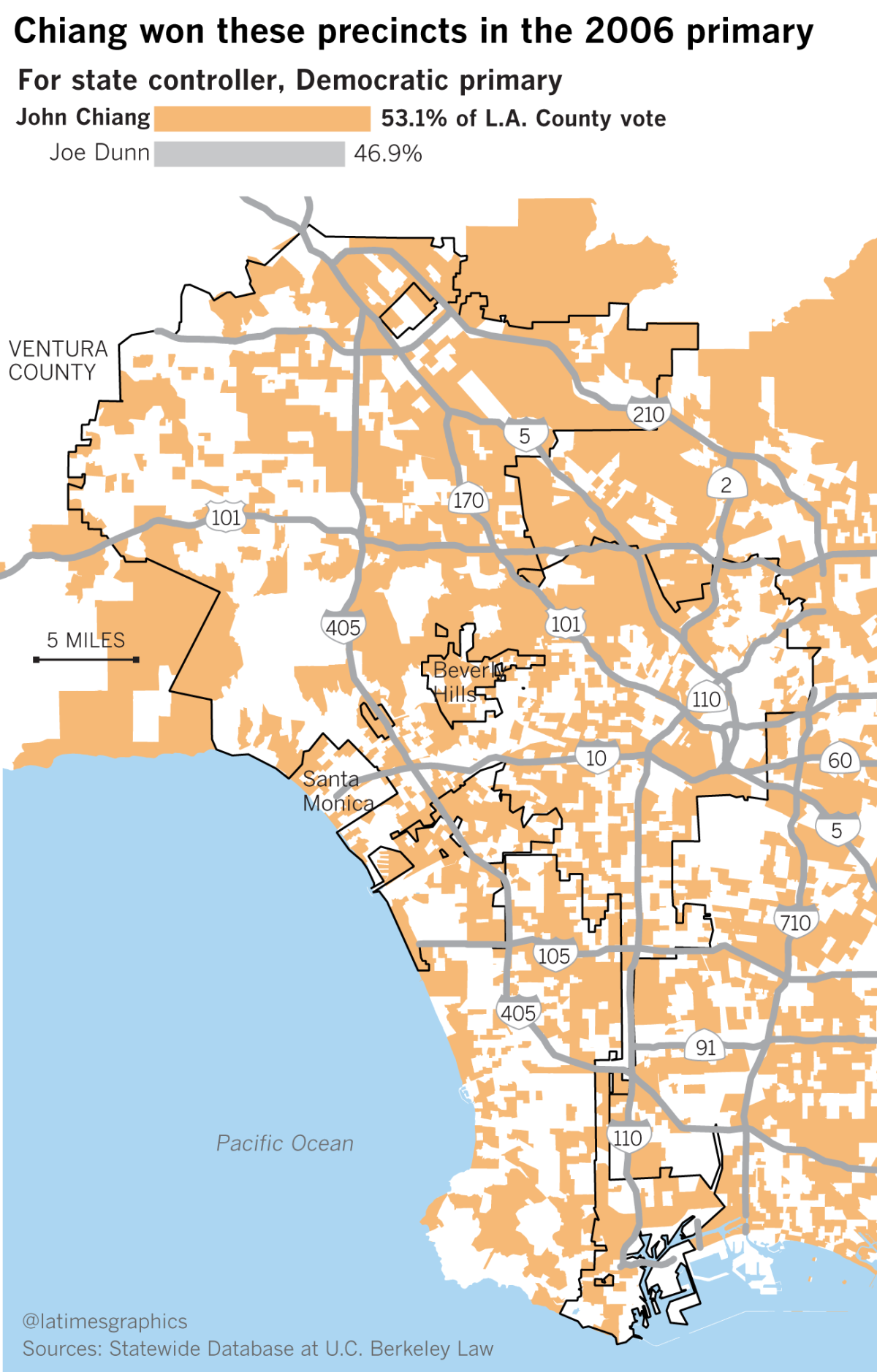

Chiang always has done well in L.A. County in his statewide runs for office. That included his hotly contested campaign for state controller in 2006, when he beat a state senator from Orange County in the Democratic primary. Chiang won the primary in L.A. County by more than 6 percentage points, thanks in part to strong support in Century City, downtown Los Angeles, Gardena, Burbank, Glendale and Van Nuys.

Newsom, who became a darling of the left as mayor of San Francisco when he directed the city to start issuing same-sex marriage licenses in 2004, glided to victory in his first campaign for lieutenant governor.

But he had some trouble in L.A. County in the 2010 Democratic primary. Just like the governorâs race, Newsom was challenged by a well-known Democrat from L.A., city councilwoman and homegrown political scion Janice Hahn. Hahn, the daughter of former county supervisor Kenneth Hahn and sister of the former L.A. mayor, beat Newsom by 14 percentage points in the county. Newsom fared best in some of the regionâs most affluent areas, including the Westside, Hollywood Hills, West Hollywood, Santa Monica and Malibu.

Newsomâs margins in Northern California may make up for a mediocre performance in Los Angeles, but if he can boost his numbers in L.A. in the June primary, that would cement his front-runner status.

He says heâs visited Southern California at least once a week since he was elected lieutenant governor.

âWeâre doing a lot of town halls around the region. And weâre not taking anything for granted,â Newsom said.

Delaine Eastin won L.A. County in her successful statewide runs for state superintendent of public instruction in 1994 and 1998. But polls put the Democrat, who lives in Northern California, with county support at 6% or less. A Public Policy Institute of California survey found 55% of county voters had never heard of her.

For the most prominent Republicans in the race, Rancho Santa Fe businessman John Cox, Huntington Beach Assemblyman Travis Allen and former U.S. Rep. Doug Ose of Sacramento, prospects in L.A. County also border on grim. Hillary Clinton crushed Trump by a 3-to-1 margin in the county last fall.

Democrats have a 33 percentage-point voter registration advantage over the GOP here. Even âdecline to stateâ voters outnumber Republicans by 360,000.

FOR THE RECORD

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the City of Los Angeles has the largest Native American population in the U.S. The city has the second largest Native American population.

Twitter: @philwillon

Updates on California politics

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.