Opinion: Shannen Doherty was painted as a bad-girl âVeronicaâ stereotype. She deserved better

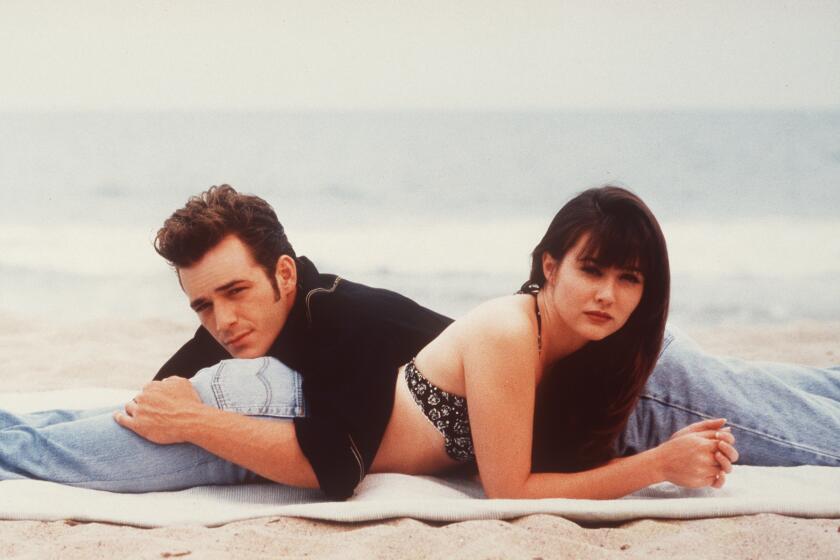

As Brenda Walsh on âBeverly Hills 90210,â Shannen Doherty represented a bit of reverse typecasting. She was a dark-haired, sultry beauty, her green-eyed gaze peeking out through long bangs, but she played the good girl â a Midwestern virgin lost in the Sodom of Beverly Hills. Similarly cast against type, an angelic-looking blond, Jennie Garth, played Kelly, a worldly and experienced SoCal vixen â Brendaâs best friend and, sometimes, treacherous rival.

Had Aaron Spelling deliberately set out to reverse the Betty/Veronica pop-culture (and deeply Eurocentric) stereotype, in which blonds are virtuous and brunets dangerous? Maybe. (The old Hollywood version of this is the 1950s tabloid feud between sexy brunet Elizabeth Taylor and sweet blond Debbie Reynolds, who were friends before Taylor âstoleâ Reynoldsâ then-husband, Eddie Fisher.)

But the age-old dichotomy came roaring back anyway, in the form of a â90210â backstage plotline: Doherty developed an off-camera âbad girlâ reputation. Rumors flew about her allegedly demanding and entitled behavior on set. She was a Veronica, after all. Co-stars â reportedly including Spellingâs daughter, Tori â complained, until finally, in a much-publicized move, Doherty was fired. The fallen angel was expelled from Eden.

Shannen Doherty, who died Saturday, was as complex as the âBeverly Hills, 90210â character that she was best known for, loved and hated, and simultaneously revolutionary.

It was a setback for Doherty, but also a classic example of how much pop culture relies on stories of good and bad girls, both onscreen and off. However difficult male actors might be, we rarely get so much detail about their professional behavior. Nor do men elicit anything like the level of moral judgment women do. But womenâs (especially young womenâs) âgoodnessâ â whether as depicted in a television show or assessed in their personal lives â remains an inextricable part of their image.

Doherty was eventually welcomed back into the Spelling universe with a starring role in âCharmed,â a series about three brunet sisters who happened also to be actual witches. Her redemption seemed complete â all three were good witches! But even here, the storyline suggested the double lives all women are suspected to have: The âCharmedâ sisters must keep their powers a secret and try to live ostensibly normal lives (there are shades here of the old 1960s shows about women forced to hide their magical powers: âBewitchedâ and âI Dream of Jeannie,â in which each main character was virtuous and blond but had a disruptive brunet alter ego).

Yet Doherty was brought low again by her own troubling offstage self. She left âCharmedâ in 2001 amid rumors she was slated to be fired. The onscreen Glinda-the-Good-Witch persona could not outweigh the offscreen Wicked-Witch-of-the-West one. âCharmedâ had always been about the epic battle between good and evil, and conveniently, whatever her conscious intention, Doherty appeared to keep playing out this struggle herself. Her life and behavior just fit remarkably neatly into this conventional paradigm.

Holly Marie Combs, who co-starred with Shannen Doherty on the original âCharmed,â gave a heartfelt tribute to her onetime sister-witch, who died Saturday.

Dohertyâs biggest struggle, of course, came with her cancer diagnosis in 2015, which she met with dignity, grace and frankness, demonstrating the maturity and wisdom sheâd acquired with age. She became a vocal advocate for educating the public on cancer. She gave frequent updates about her own condition. When her health worsened, in 2023, she launched a podcast, âLetâs Be Clear,â talking honestly about her life, career, illness and relationships.

Amid this medical crisis, Doherty seemed to find comfort in spirituality. In one 2023 interview about her grim prognosis, she said: âIâm not afraid of death, because I know where Iâm going. ⌠I think I would be afraid of death if I wasnât a good person. But I am.â

As her remarks remind us, the good-girl/bad-girl motif is really just a small part of a much larger, more profound narrative about heaven and hell, sin and morality, a narrative that underlies much of Western civilization â and with which women are often far more burdened than men, doomed to be assigned one end or the other of this spectrum.

Doherty could not win her battle with cancer, sadly, but she did triumph â over her bad-girl persona, the decades of bad publicity and the constraints of a pop culture storyline that long predated her and will likely long outlive her: the one in which young women, especially those who fit a certain stereotype of the sexualized, dark-haired beauty, are scrutinized, judged and often convicted in the public imagination. It should not take the tragedy of cancer, though, to be seen as worthy of redemption, or better still, to be worthy of a more complex, honest and human narrative.

Rhonda Garelick is a distinguished professor of English and journalism at Southern Methodist University and the author of a forthcoming book on fashion and politics.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.