Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s ‘The American Daughters’ boldly confronts the legacy of slavery

- Share via

Book Review

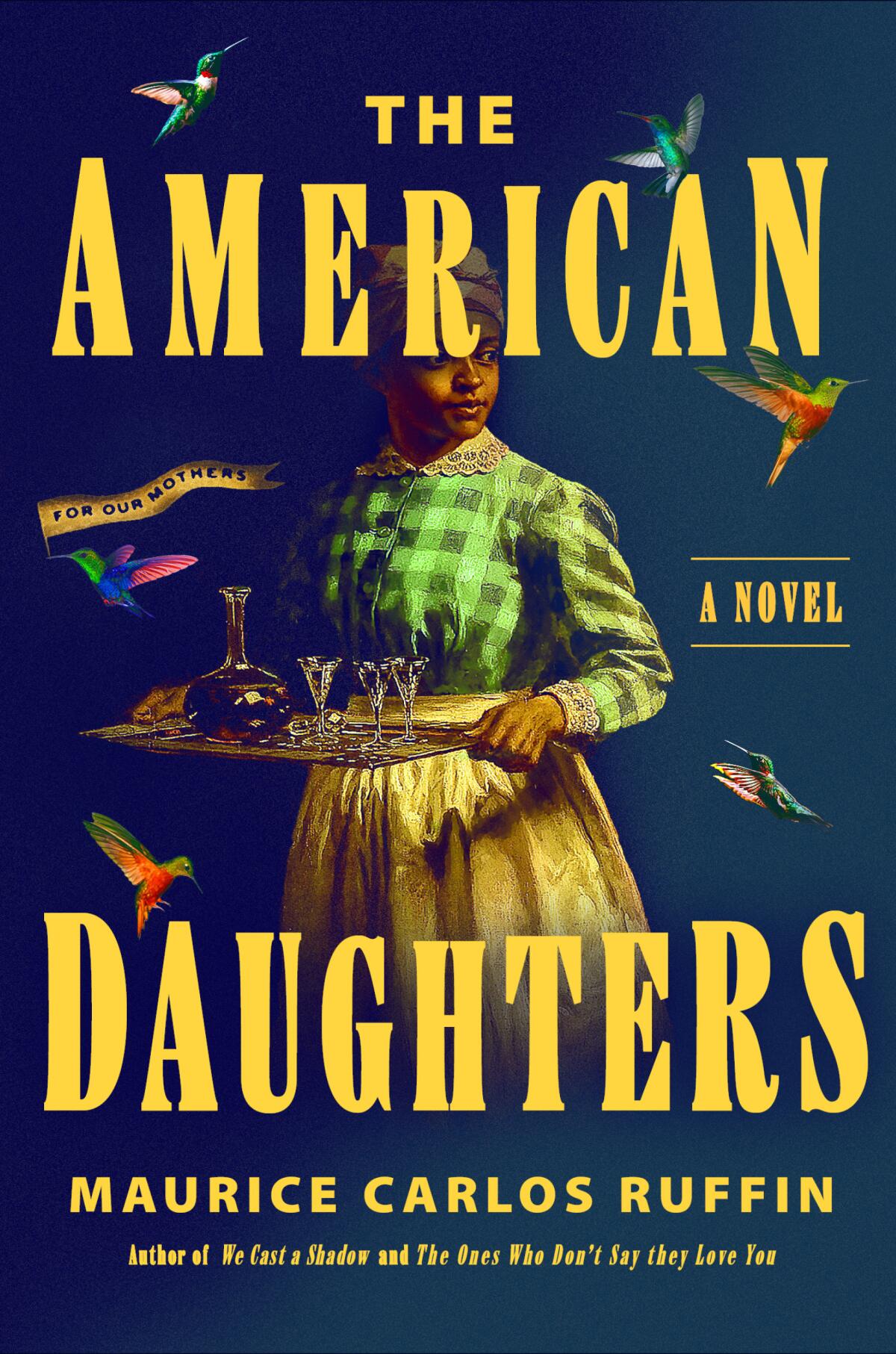

The American Daughters: A Novel

By Maurice Carlos Ruffin

One World: 304 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Historical fiction has long had associations with the overwrought, unnecessary and myopic nostalgia that suffuses books such as Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone With the Wind.” But today the genre is better known for its capacity for provocative interrogation. A sublime example of the form is, of course, Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Beloved.” And just this past year, the two-time National Book Award winner Jesmyn Ward looked backward to write “Let Us Descend.” These examples preoccupy themselves with the still-festering American wounds brought about by the institution of slavery and its legacy. Now someone with the training of a lawyer and the heart for storytelling joins this chorus.

With his bold and ambitious third work of fiction, “The American Daughters,” Maurice Carlos Ruffin approaches the historical novel on a slant. After setting aside a career in law for creative writing, Ruffin published his first novel, “We Cast a Shadow,” in 2019. A deeply satirical novel, skewering racism, it was set in an unnamed Southern American city that resembled his hometown of New Orleans. His 2021 book, “The Ones Who Don’t Say They Love You,” was an evocative love letter to New Orleans, full of contemporary stories that captured the rhythm and blues of the city. Given these works circling New Orleans and the lives of its Black residents, it comes as no surprise that Ruffin is pivoting to confront the past.

Are utopias becoming a trend in fiction during this dystopian era? The debut novel from Phillip B. Williams, ‘Ours,’ embraces magic without ignoring reality.

An antebellum-era novel set in Louisiana, primarily in New Orleans’ French Quarter, “The American Daughters” tells the story of a mother and daughter, Sanite and Ady. The two are sold on the bank of the Mississippi River to serve wealthy landowner John du Marche in his French Quarter residence. This arrangement offers a reprieve from the backbreaking physical labor upriver on du Marche’s plantation; however, psychological dangers such as isolation and sexual violence loom in the city. There is no escape from sadism under enslavement.

Ruffin creates an intimate and atmospheric portrait of life in New Orleans through interior scenes divided between opulence and abuse. He brings to life the lively energy of the French Quarter streets, teeming with characters both nefarious and benevolent. The tension between these two worlds reflects the times; freedom persists just outside the courtyard door.

Indeed, liberation awaits. Eager to move the plot along, Ruffin assumes a fast clip as Ady and Sanite’s bleak experience in New Orleans leads to an unexpectedly straightforward escape. Life on the run offers an opportunity to flesh out the women’s backstory before mother and daughter are bound again in slavery on what Ruffin throughout the book refers to as “the slave labor camp, also known as a plantation.” It’s a verbal tic that feels overstated until you recall that Ruffin has revealed his puppeteer’s strings in the prologue. Overwrought or hackneyed language — such as describing an unexpected skill as feeling “like hope” — are not the sign of clichéd writing in the case of “The American Daughters.” They’re visual markers within a text that demands interrogation.

The reason for this active detective work is that Ruffin himself asks the reader to question the text. In his prologue, he makes it clear that what follows are stories within stories. He offers notes from a researcher’s files that include a translated fragment of a historical document and a conversation transcript regarding a book that shares the name of Ruffin’s novel. He establishes an outside perspective and awareness of the novel as a story within a story. He shares a quote from a 2017 interview with a distant relative of the real-life Ady who says, “I never lied, now. I admitted the work I did to fill the gaps and complete the narrative. By this time, the book had been reprinted twice. I played down my involvement because I never wanted the hoopla to be about me. It was her story, you feel me?” The transcript (a stylistic device that signaled inspiration from Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale”) makes clear that “The American Daughters” is compromised. It’s a story that’s been borrowed and rewritten and passed off for fiction when it’s a composite of truth and fantasy.

Lost cause narratives sometimes have been powerful enough to build or destroy political regimes. They can advance a politics of grievance.

While on the run from du Marche, Ady and Sanite recognize the impossibility of freedom in a world that grants them no place to live autonomously without fear of violence. Unburdening herself to Ady, after being caught and returned to du Marche’s clutches, Sanite muses, “The only thing I’ve ever wanted was life with a house and you and your dad to be unbothered by the like of white folk. But the older I get, it seems that ain’t possible.” Ady counters, “That don’t make any sense. You always talking about freedom.” Sanite explains the elusive nature of freedom during the mid-19th century for a Black woman bound by a “world that’s slanted.” Ultimately, it’s Ady who embodies freedom to Sanite. “You my freedom. My life out there don’t mean anything. My life in here ain’t much either. But my daughter. My joy. That’s why we here.”

Freedom deferred to children is an ever-shifting desire. Its fulfillment comes through action, which forges a link that bonds mothers and daughters across time — and beyond death. Rebellion is an expression of freedom. But before mother and daughter can participate in a broad and sweeping rebellion, a series of tragic events unfolds that ultimately brings Ady back to du Marche’s French Quarter home. Here, without her mother, she strikes up a powerful friendship with a free woman of color named Lenore. Together, they forge a bond that subverts the power wielded by du Marche, his fellow slave owners and Confederate rebels.

Ady joins Lenore and others in a resistance group called the Daughters, whose name is a nod to the Daughters of the American Revolution. The Daughters is an action-driven organization devoted to liberation that has been passed down through generations. This, too, is forecast at the beginning of the novel.

‘The Fraud,’ Zadie Smith’s sixth novel, cleverly follows the famous 19th century trial of a fraudulent claimant who becomes a populist hero. Sound familiar?

Lenore is a miraculous figure: a business owner, an unmarried woman who commands respect from slave owners as well as her father. Her presence in the book not only raises the stakes (will her influence prompt Ady to escape du Marche’s clutches again? Does their friendship transcend platonic affection?) but seems almost too good to be true. Were there actual women like Lenore or is she pure invention? What does it say that we know so little about free women of color?

Here Ruffin’s legal background lends a hand; the details in his fiction are his evidence, notes of proof. Stories are not canon. Narratives offer one lens on a story that contains endless variations. To whom do they belong? Who should we trust? The idea of possession — people as property, stories as intellectual property — becomes a slippery object in Ruffin’s hands. Mothers and daughters share trauma, stories overlap and swap. But the telling and retelling (what we know as slave narratives, oral histories, fictionalizations, academic interpretations) of stories is something that defies containment. Imagination is a conduit of freedom.

This is the real story that Ruffin wants to tell. Late in the novel, an admission surfaces: “The women were well aware that whatever the Daughters accomplished would be forgotten for all time. Ady knew that she, too, would be forgotten.” So what endures? It’s the ongoing storytelling and capacity for dreaming that keeps us free.

Cracking open the very idea of historical fiction, Ruffin dares to ask us more from history and culture. The concept of freedom has always been up for debate. By looking backward, we recognize our own agency. With his novel, Ruffin urges us to lay claim to an odds-defying legacy of determination and willful optimism.

Lauren LeBlanc is a writer and a board member of the National Book Critics Circle.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.