Opinion: Who’s to blame for the United Auto Workers strike? Start with Wall Street

- Share via

The United Auto Workers are striking against General Motors, Ford and Stellantis — the Big Three — to make up for lost ground. Since 2003 the average hourly wages of UAW production workers have declined by 30%, adjusting for inflation. A large portion of those losses came when the autoworkers were compelled to help bail out GM in 2008 as it went bankrupt.

The worker concessions included a decadelong wage freeze for those hired before 2007, lower pay and benefits for new hires including the elimination of defined pensions, and the shift of the healthcare benefit fund from the company to the union. The concessions also permitted the use of lower-paid temp workers who could earn $18 an hour working alongside a longtime employee earning $32 per hour while doing the same tasks.

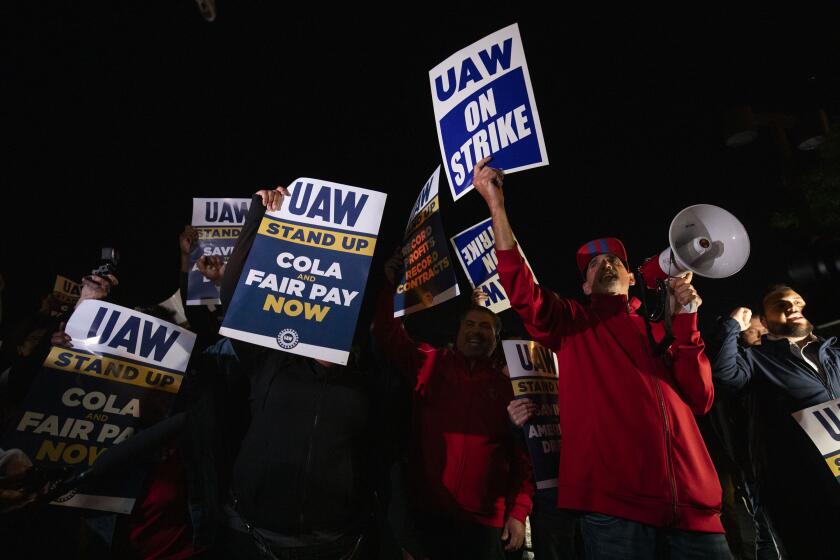

About 13,000 autoworkers went on strike at three plants after contract talks over wages and benefits broke down late Thursday.

The union wants to end these concessions while also gaining a 40% wage increase over the next four years to match the 40% compensation increases received by Big Three chief executives over the last four years. The UAW has said that if contract negotiations don’t advance by Friday, it will expand the strike beyond the three plants currently targeted.

The federal government’s $80-billion bailout and worker concessions saved GM. Many who supported the bailout expected the company, when it returned to profitability, to invest heavily in electric vehicle research, development and production: The taxpayers saved GM, so now GM should help ameliorate global warming that harms us all.

But Wall Street had other ideas. In 2015 it swooped in to capture these newly minted profits by pressuring GM management to conduct a stock buyback of $8 billion. Made possible by the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Rule 10b-18, put in place in 1982, buybacks are a method of profit extraction allowing companies to use their profits to buy back their own shares, thus increasing the value of all outstanding shares. Hedge funds and the like take large stock positions in companies, demand buybacks that quickly increase the price of their shares and then cash out with significant profits.

The failure of the Clinton-era corporate responsibility initiative helps explain why we’re seeing so much worker militancy and government activism today.

This pattern happened with GM in the years following the bailout: The giant hedge fund Appaloosa Management joined with other funds to buy up 2.1% of GM shares. These efforts succeeded and then some: GM announced $5 billion in buybacks in March 2015, another $4 billion later that year and another $5 billion in 2017. At the same time, the company planned to cut 14,000 jobs and idle five automotive plants.

In addition to rewarding Wall Street share-sellers, stock buybacks also increase the pay of top corporate executives. As of 2021, stock awards and options made up 82% of total CEO compensation. Approximately 75% of all non-financial corporate profits went to stock buybacks in the decade after the automaker bailout. In the 12 months ending in March 2022, buybacks transferred $1.5 trillion of corporate profits to share-sellers. Stellantis, which purchased Chrysler, Fiat and Peugeot in 2021, even had the audacity to announce a $1.6-billion stock buyback in February ahead of negotiations with the UAW.

Today none of the Big Three are worried about bankruptcy: Collectively they are expected to earn $32 billion in profits in 2023. The automakers claim those profits are desperately needed to make the historic shift to electric vehicles and fend off their nonunion competitors such as Tesla. Meeting the UAW demands, they claim, would cut those investments while forcing the companies to move more production to lower-wage areas here and abroad.

As usual, the media and politicians are blaming the possibility of an auto strike on the auto workers union, but company managements are the guilty parties.

What they neglect to say is that Wall Street’s shadow also hovers over these negotiations. As Stellantis made crystal-clear when it authorized stock buybacks this year, the industry is more than willing to divert badly needed investment funds into the pockets of top executives and powerful Wall Street firms.

A stock buyback, of course, does not strengthen the company. It does not create investment in new plants and equipment. It does not upgrade the skills of the workforce. And it does not improve health and safety or increase research and development to mitigate climate change. In fact, it decidedly detracts from all of these critical functions by eating up the money to fund them. Billions spent on buybacks means billions less not only for workers’ wages but also for developing high-quality, affordable electric vehicles to forge the transition to a green, sustainable economy.

For the first time in a generation the labor movement is held in high esteem by the American public. It is widely understood that working people need the protections only collective bargaining can provide. This puts unions like the UAW at the forefront of the struggle to protect jobs and the environment. Perhaps these difficult negotiations can help us all realize just how much stock buybacks threaten both economic fairness and the health of our climate.

Les Leopold is the executive director of the Labor Institute and author of the forthcoming book “Wall Street’s War on Workers: How Mass Layoffs and Greed Are Destroying the Working Class and What to Do About It.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.