Opinion: Hawks take over my backyard each year. Their visits prepare me to return to my classroom in the fall

- Share via

I have been thinking a lot about the hawks who return to live in my backyard late eachspring. Are they Cooper’s hawks? Sharp-shinned? Even practiced birders might relent and log these birds as either/or.

In my neighborhood, a pair of small but vociferous falcons have lately been troubling my hawks, taking turns dive-bombing them in spectacular displays of aerial loops and twirls, intimidation through speed, agility and determination. The hawks just take it, hunched and resigned on a nearby telephone pole, like mute, stationary gargoyles guarding their castle.

It is merlins — small falcons once known as “lady hawks” in the medieval hierarchy of falconry — that are hectoring my hawks. Their size belies their ferocity. Their association with the female might make one think that my affection lies with these small but mighty birds, but it does not. Hawks speak to me of home. It is to them that I pay my allegiance.

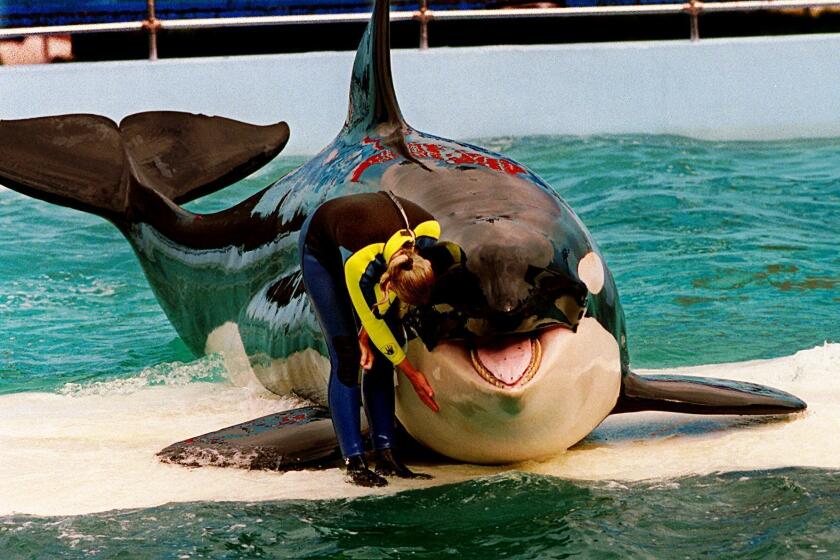

Lolita, a.k.a. Tokitae, is on track to be released from the Miami Seaquarium to her native waters on the West Coast. Her journey is a story of humans devaluing animal life.

My hawks have built a great hulking nest — a safe house — in the pine tree that starts in my yard. To the dismay of my neighbor, some of its tangled branches and messy needles fall into his. The nest, however, is on my side of the property line, so I have claimed the castle, so to speak, even though during nesting season it is the hawks who rule my yard.

I have sometimes wandered into what is clearly their domain to perform some inconsequential chore — going to the shed for a hammer, scratching my dog’s ears — only to be swooped down upon and warned that my time outside is over. When these battle lines are drawn, I retreat.

Sometimes when I am reading on my deck, one of my hawks will land on the jacaranda tree above me, almost within touching distance. He and I will sit in what, at best, is an uneasy detente, his eyes trained on me, considering, it seems, just how meek and ridiculous I am. In my subservient position, I have ample time to consider the color of his wings, the rust-colored striations on his chest, the shape of his head. Yes, I think, Sharp-shinned hawk. And after he has turned and left, I rush inside to check my field guides — and my old doubts settle in yet again. There was a certain squaring off of the head that speaks of a Cooper’s hawk, and my insistence on a correct label for my bird remains unmet.

Perhaps this struggle is not a bad thing. Perhaps labels are meaningless. A label, a definitive name, “is nor hand, nor foot, nor arm, nor face,” nor any other part of consequence.

The inability to label these birds reminds me of my middle school classroom, where the disparate voices of my students hold sway, and their temperaments defy absolute identification. They are finding the allure of their own voices.

Though I am not a falconer (I do not “a-hawking go”) it strikes me that the art of falconry has much in common with the art of teaching.

Having children is an emphatic statement of hope, yet ‘Earth breakdown’ from climate change awaits. Taking decisive action is the best way to give kids hope.

I like to think of my classroom as a safe house, filled with students defying labels. Is this boy, who refuses to look at the screen when I show photographs and films, on the spectrum? How would I label a girl who moves stealthily amongst her peers yet shows such elegant vulnerability in her prose? I know that the boy who swaggers into the room, chest puffed out, making himself fill the space with his discontent, is doing so to hide his sadness over his parents’ divorce. How then should I label him?

It is best, I think, to see my students as fledglings, whose brief forays into the world have not yet equipped them to take on all of its wonders and ills. Better to log them as either/or and appreciate their delicious complexity for the brief months that I enjoy their company.

As summer wanes, and months of being awakened by the calls of my hawks, living under the scrutiny of their gaze, observing their nesting, soaring, diving and landing, they have left me. The silence overwhelms my yard, much as it descends upon my classroom each year when June arrives.

But now that my hawks are gone I can tidy up: shelve my binoculars, rake up the pile of blue jay and mockingbird feathers beneath their nest. I can even sleep in a little later — a brief respite before I prepare for the new school year.

Wendy Schramm lives and teaches in North San Diego County.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.