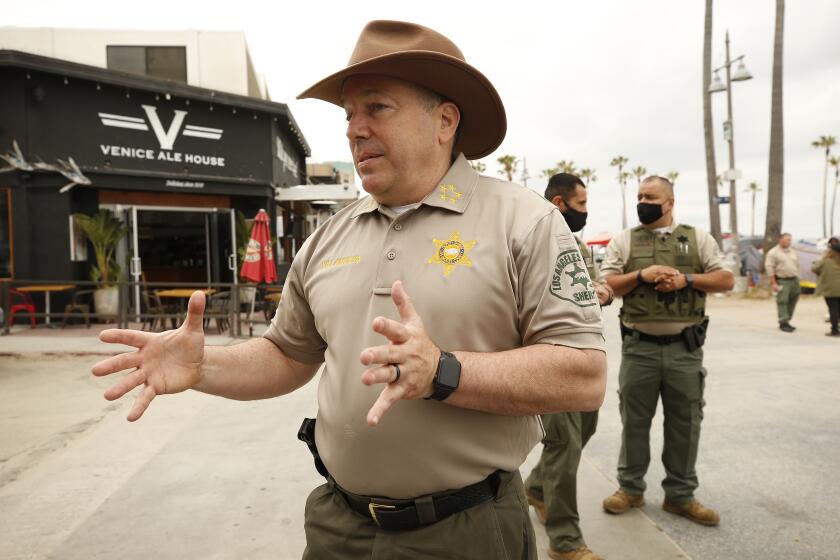

Editorial: What Sheriff Villanueva got right (and why it wasn’t enough)

- Share via

Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva was so overwhelmingly repudiated by voters in his bid for a second term that it’s easy to conclude that he was wrong about everything, and that he leaves behind no lessons or insights of particular value.

That’s not entirely the case. Villanueva’s tenure was disastrous for the county and his department, but he got a few things right, usually despite himself. Robert Luna, who becomes sheriff Monday, would do well to take heed. So would the people of Los Angeles County.

Villanueva’s most obvious on-target policy was to remove federal immigration officials from county jails. He saw, just as Los Angeles Police Department leaders saw decades earlier and state lawmakers more recently, that residents — even those in jail — must be able to approach local law enforcement agents without fear that doing so will make them or their families targets for deportation. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents have their jobs to do, and sheriff’s deputies have theirs. They do them best while staying out of each other’s way.

Villanueva understood the needs of the county’s immigrant and working-class families in other ways as well. He correctly noted that the most serious theft problem in the county is not high-profile crimes such as shoplifting, but wage theft — when employers refuse to pay workers what they owe them, to the tune of about $26 million a week in Los Angeles County alone.

The Los Angeles County sheriff’s election is more significant for Alex Villanueva’s defeat than Robert Luna’s election

In response, he created a wage theft unit, which, if judged by the amount of money it recovered, failed miserably. Wage theft falls under the jurisdiction of the California Labor Commissioner’s Office within the state Department of Industrial Relations, and it’s not clear what value is added by a sheriff’s participation. In better hands, though, the department might play a constructive role.

Much of what Villanueva got right can be found in the crevices of what he got astoundingly wrong, especially in his claims that all of his critics were part of a conspiracy against him.

For example, he carried a grudge against what he considered the unfair treatment of himself and other deputies by department superiors during his career. Complaints about perceived slights and injustices are typical of any large, bureaucratic organization. But at least some of Villanueva’s complaints bore a ring of truth and are important to the future of the department and the people it serves.

There has never been a sufficiently thorough outside investigation into whether promotional exam results during the reign of Undersheriff Paul Tanaka (later sentenced to federal prison for obstruction of justice) or even before were unfairly doctored, or whether some favored personnel were improperly given extra time and reduced duties to better prepare and earn higher scores, as Villanueva and others alleged. But there was enough talk among the ranks about such shenanigans to make deputies openly question the fairness and legitimacy of the promotional system.

Robert Luna would be a much better sheriff than the disastrous Alex Villanueva

Should county residents care about Sheriff’s Department promotions? Yes. When confidence in official processes disappear, members of an organization will develop alternatives. Off-the-books relationships and codes of conduct supplant rank and chain of command. It’s a phenomenon that produces criminal street gangs, and, quite possibly, exacerbated the problem of deputy gangs within the department, and raises the specter of armed officers on the street and in the jails playing by rules they make up themselves.

Villanueva’s response to perceived unfair treatment was unsound. He tried to rehire deputies who he and trusted associates claimed had been improperly terminated, instead of referring the issue to outside reviewers (some terminations already had been upheld by the civil service commission). Instead of correcting an allegedly unfair process, he substituted in his own equally whim-based scheme.

But the underlying concern about corrupt processes was on target and has yet to be fully addressed.

Villanueva was also right about a basic and costly structural failure in county government. The county supervisors “are both branches of government in one body,” he told the Los Angeles Times editorial board. “There should be a county mayor. So you have a true executive branch of government and [the supervisors] should only be a legislative branch of government.”

He’s correct. County government fails to offer the checks and balances that characterize federal, state and city governments, and the county and the people suffer from it in the form of insufficient representation and transparency.

But, as was typical, the sheriff steered his accurate observation into baseless conclusions. He claimed the Board of Supervisors was corrupt, along with everyone the board appointed who criticized or thwarted his mismanagement: the Civilian Oversight Commission, the inspector general, county counsel, the chief executive officer. The record is devoid of any meaningful evidence that any of those bodies or individuals engaged in misconduct or fell short in their duty to keep the sheriff operating within the law and sound policy. Villanueva’s refusal to comply with subpoenas or turn over information discredited him and his department. The raid on the homes of Supervisor Shelia Kuehl and commission member Patti Giggans (which Villanueva tried to distance himself from) was the final straw.

And yet, the commission and the inspector general, and the board’s new power (in the wake of a successful ballot measure) to fire a sheriff for cause, are at best workarounds that fail to fix a basic problem: The county lacks adequate checks and balances.

Editorial: Villanueva’s attempt to intimidate a Times reporter is a gaslighting assault on the press

Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s attempt to intimidate a Los Angeles Times reporter is the sort of tactic employed by tin-pot dictators and power-happy functionaries.

Nor was the sheriff completely off-base when he accused the board of shifting public funds from county workers to private contractors. He provided only the most specious evidence that contracts are corruptly awarded based on campaign contributions or personal friendship, but he put his finger on a central concern. If the county is to expand its program of referring offenders to supportive housing, drug treatment, mental health care and other services often provided by nonprofits and private contractors rather than jails staffed by deputies — as it should — there will be increasing tension between public employee unions and nonprofit service providers. And there will be a growing need to evaluate the nonprofits’ performance, and to trace the flow of public money.

Even when he properly identified problems, though, Villanueva failed to effectively solve them, except for removing ICE from the jails. His self-righteousness, his erratic temperament, his defiance of oversight, all undermined him and left his department weaker and less respected. He will not be missed. But he should be remembered — for all the things he got wrong, yes, but also for those few things he got right.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.