Op-Ed: Where will Putin steer the Ukraine war on Russia’s Victory Day?

- Share via

May 9 marks a pivotal date in Russian history and has long been important in its politics. Known as Victory Day, it is used by Russian leaders to celebrate victory over Nazi Germany by holding large military parades and nationalist ceremonies.

It’s not surprising that this year the Kremlin is using the day’s heavy symbolism to promote its savage war against Ukraine — which it has monstrously and falsely justified is a “denazification” campaign.

The war in Ukraine is at a critical juncture. Russia continues to attack along the eastern front despite estimated losses as high as 20% of its combat-ready ground forces in Ukraine. Russia also faces the risk of defections from its elite ranks. For weeks now, Moscow has launched missile attacks against Ukrainian lines of communication, hitting rail lines, warehouses and critical infrastructure to reduce the ability of Kyiv to push foreign military supplies forward and to sustain its defenses in the east and south.

U.S. military, intelligence, economic and humanitarian aid to Ukraine must keep flowing and even increase as the Russian invasion enters a new phase.

On the other side, against all odds, it looks like the Ukrainian people — with the help of a coalition of democratic nations and volunteers — are holding their own against Russian troops.

But what comes next? The answer rests on how Moscow and an increasingly isolated, paranoid and risk-taking group of Russian elites surrounding President Vladimir Putin approach Monday’s holiday.

Here are three possible paths forward in the struggle for Ukraine:

First, Putin and his generals could use Victory Day to declare what’s known as a Potemkin peace: claim victory while pulling back to lines of control that roughly match territory that Russia controlled in Ukraine in 2014, including its annexation of Crimea that year. Russia has a long history of using Potemkin villages — elaborate facades to hide uncomfortable truths — that could serve as a foundation for a new lie: victory in Ukraine.

The shooting would stop along the front line and Russia would proclaim independent states in the east and around Kherson, a city in south Ukraine. There would probably be periodic shelling along a contact line and a continuing lower-intensity conflict. Sanctions would remain in place, and while the West helped rebuild Ukraine, Moscow would focus on rebuilding its army and insulating its economy, for a future military operation. This pattern reflects a sad truth from international relations: The most likely source of conflict is past conflict. Many wars never end: They hibernate only to perpetually return, creating patterns of protracted conflict and enduring rivalry.

Second, Putin and his generals could declare martial law and conduct a total mobilization of the Russian state and society for war. This is the most dangerous path. Putin has denied that he will officially declare war on Monday, but that could change. A formal declaration of war would end any prospect of a rapprochement with the West, with Moscow showing that it’s willing to fight a long, costly war likely to further threaten bordering European states. Putin could even be pulled to expand the conflict beyond Ukraine’s borders.

There are already signs this dark future may be upon us. There are reports of a mass mobilization being discussed in Russia. The Kremlin is moving to escalate its economic war with the West, including breaking existing contracts for energy exports and denying strategic resources to countries helping Ukraine.

Even a mass mobilization, however, wouldn’t mean an immediate escalation in fighting. It would take time for Russia to train new recruits, build units and move them to Ukraine. Russia would suffer economically by putting money into its troop expansion and cutting business ties with the West. In this scenario, the open question then is what China, Iran and India would do. If Russia can align its trade and financial system to these Asian countries, then Russia can sustain a long war.

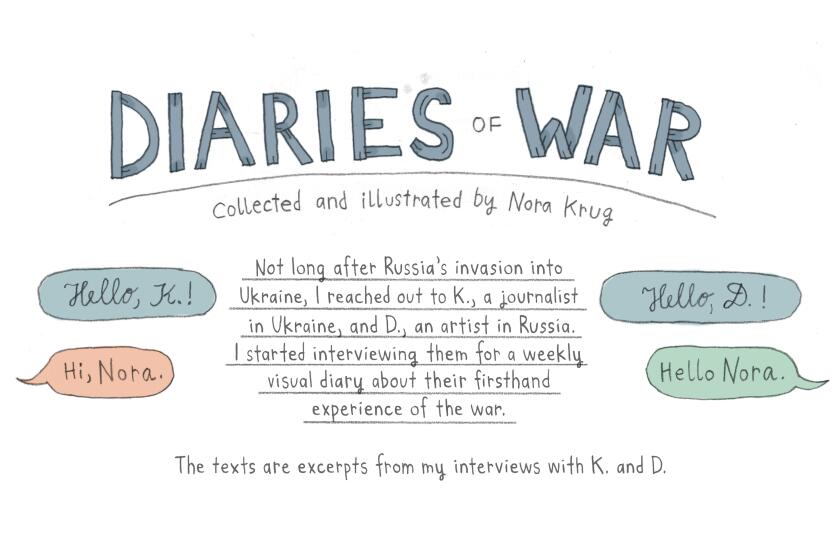

Like a carrier pigeon, K. travels from one city to another, transporting messages and belongings. D. crosses the Russian border into Latvia to look for work.

Here the history of the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s provides insights. Tehran was cut off from the world, while Baghdad received significant foreign financial and military support. Yet Iran was able to mobilize troops that conducted human-wave attacks, in which large masses charge toward the enemy at once, and fought Iraq to a bloody stalemate for more than eight years.

Third, Russia could stay the course, continuing what has essentially become a stalled offense. In this scenario, the Russian military would order the units already in Ukraine, which are suffering from high attrition levels, to attempt to seize more territory in the east using current tactics. While making some territorial gains might achieve a symbolic tactical victory for Russia, it would set the stage for a large-scale Ukrainian counterattack.

At present, Russia’s ability to find gaps in Ukraine’s defensive line in the east has proved limited, raising the risk that Kyiv could counterattack. If Ukraine can isolate Russian forces, it creates the possibility of mass surrenders, a common outcome seen historically when militaries employ the blitzkrieg and kesselschlacht strategies to encircle the enemy. But even this outcome is unlikely to end the war, because Russia still retains its nuclear arsenal and long-range missiles that it could potentially employ.

The tragedy is that any of these paths — Potemkin peace, long-attritional struggle or a Ukrainian counterattack — means that this war is not likely to end soon.

Cease-fires don’t guarantee peace. The only people who can stop this war are the Russians. But Putin has locked up Russian citizens for questioning the war. While Western nations hope sanctions will turn Russian elites against the Kremlin, no cracks in the regime have emerged. This political reality sets the stage for a long, brutal struggle that will require continued support for Ukraine and increased diplomatic efforts to keep Moscow isolated.

Benjamin Jensen is a professor of strategic studies at the Marine Corps University School of Advanced Warfighting and a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.