Newsletter

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

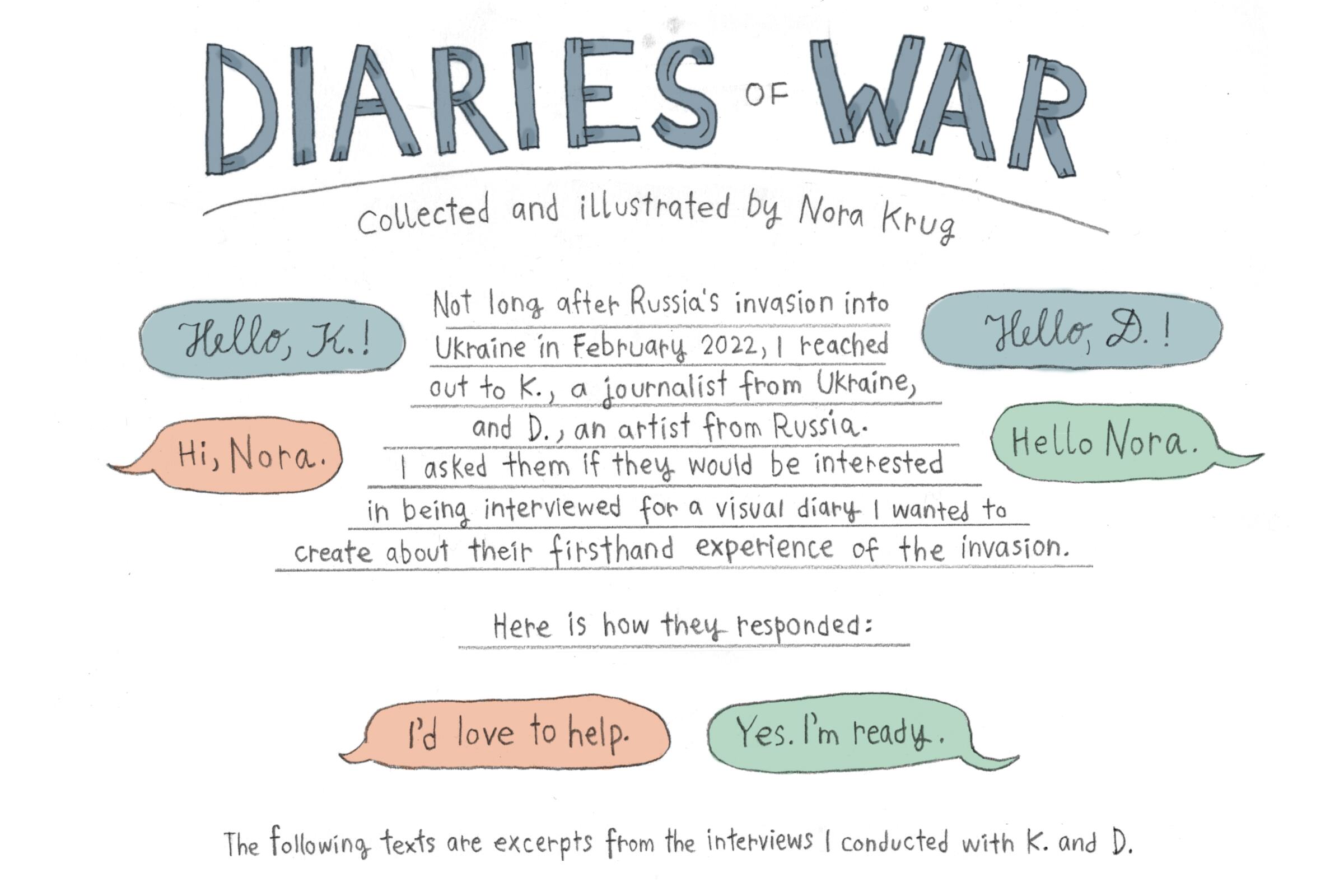

The stories of K., a journalist in Ukraine, and D., an artist in Russia, as they deal with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the trauma and threats to their lives.

K. goes to the Lviv train station, where thousands of people are congregated. D. tries to find a way to leave Russia soon.

D. recalls demonstrating against Alexey Navalny’s arrest and being encouraged by the crowds opposed to Putin’s regime. K. hopes to get her kids out of Ukraine as she stays to report on the war.

D. decides to emigrate to Riga, but fears he can’t make money there. K. takes her kids to Copenhagen to safety, but her husband remains in Ukraine, unable to get out.

D. finds that it’s too dangerous to talk about the war to anyone who isn’t a friend. K. interviews Ukrainians in Mariupol, a city nearly destroyed by shelling.

D. tries to cross the border into Finland, but is turned back because he lacks a work reason. K. questions how to live in a world where the atrocities committed in Bucha are possible.

D. considers what it means to be Russian now. K. returns to Lviv to deliver helmets and protective vests to journalists, one thing that could make a difference.

K. returns to Kyiv and reports from a nearby village that survived the Russian attack. D. sees a ‘Z’ displayed in the window of a neighborhood school and wonders what the parents will do about it.

D. wishes for Putin’s death while St. Petersburg prepares for Victory Day on May 9. K. interviews a woman whose son was executed for no reason by Russian soldiers in Hostomel, a city northwest of Kyiv.

Like a carrier pigeon, K. travels from one city to another, transporting messages and belongings. D. crosses the Russian border into Latvia to look for work.

K. is scared for her reporter colleagues and distressed to think that Putin’s death won’t change Russia’s actions. D. goes to a concert by a Ukrainian singer and feels ready to cry.

K. see hundreds of dead Russian bodies in refrigerated trucks in Ukraine and with no one taking them back to Russia for burial. D. hears that many people in Latvia, where he has moved, support Putin.

D. worries that people in Latvia will shun him because he’s Russian. K. tries to avoid speaking to Russian acquaintances because she is so filled with anger at their silence.

D. considers what Russian cultural identity means for him, a native of Saint Petersburg. K. explains her roots in Ukraine and her connection with Russia.

K. goes to the frontlines of the war in southern Ukraine to report on the residents there. D. drives from Moscow through Belarus to get to Latvia, and ponders a future in limbo.

D. talks about neo-Nazis in Russia and remembers his friend who as killed by them 17 years ago. K. discusses antisemitism in Ukraine and Putin’s false justification for the war.

D. talks to his sons about the cause of the war. K.’s young son is growing up fast, living apart from his parents because of the war.

D. worries about the European Union’s potential visa ban on Russians. K. ponders how art fits into this world of war and plans for the winter.

K. considers what it would be mean to carry a gun to defend your country. D. says if he’s drafted by the Russian army he would refuse to carry arms and be willing to go to prison instead.

D. considers his generation’s mistake in ignoring politics. K. cries when she sees the videos of Ukrainian soldiers liberating towns from Russian occupation in the Kharkiv region.

K. is reunited with her husband in Copenhagen and wonders about a friend who was taken prisoner by the Russians. D. flees Saint Petersburg for Helsinki to avoid being conscripted into Putin’s army.

K. considers whether there is an immediate future for her family in Ukraine. D. believes Russia has lost this war and finds it impossible to imagine a future there.

D. lands in Paris, hoping to starting a life there. K. visits her family’s empty apartment in Kyiv, which now feels like a haunted house.

D. considers personal guilt and the collective guilt of Russians for the war. K. finds that only the temporary is permanent in wartime.

D. thinks Russians have never recovered from the traumas of the post-Soviet era. K. visits liberated Kherson and talks to people who survived the Russian occupation.

K. says everyone in Ukraine is worried about the winter. You can’t live in a house without a roof. D. sees a play about what’s happening to Ukrainians and feels ashamed.

K. thinks about how the war has affected old friendships. D. considers all that will need to be done by Russia to atone for its attack on Ukraine.

D. spends New Year’s Eve in France, pondering his wish for Putin to die. K.’s young son cries on seeing President Zelensky’s New Year speech.

D. reads about the bombing of an apartment building in Dnipro, another crime by the Russian army. K. learns about an Ukrainian videographer shot dead in Donbas and is paralyzed with grief and fear.

K. recovers from salmonella in Kyiv, and dreams of returning to Crimea one day. D. meets two Ukrainian artists in France and is grateful they can have an open conversation.

D. returns to Saint Petersburg to see his wife and kids for a short visit, and hopes for the war to end. K. visits Babyn Yar, the site in Kyiv where more than 33,000 Jews were murdered during World War II, and feels a connection to today.

At the one-year anniversary of the war, K. believes the hate Ukrainians have for Russians will remain for the next generation to resolve. D. reconsiders his decision to leave Saint Petersburg, and worries that he’ll lose his emotional connection to his children.

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.