Opinion: Can Virginia reject its racist past and ban the death penalty?

Since the earliest days of European settlement of North America, Virginia â first as a colony, then as a state â has executed more people than any other jurisdiction in the United States. But in recent years it has moved away from capital punishment, with only two people currently on its death row, no executions since two in 2017, and no new death sentences since 2011.

And now Virginia may be on the verge of banning the practice altogether, which would make it the first of the secessionist Civil War states to formally end a practice inextricably tied to slavery and its legacy of racism. Hereâs hoping it wonât be the last.

Efforts have been made in Virginia before to end the death penalty, but they were unsuccessful in the traditionally conservative state. But as demographics have changed in Virginia over recent years, Democrats won control of the state Legislature in the November 2019 elections, joining Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam, who has made ending the death penalty in Virginia a priority.

And it might happen this time. A key state Senate committee approved an abolition bill Tuesday, and local reports suggest the proponents have enough support in the Legislature to enact the ban.

You know, when it comes right down to it, itâs been a fast four years. Or not.

According to an analysis by the Death Penalty Information Center, from 1608 through 2019 Virginia executed 1,390 people, with 113 of those coming after 1976 when the Supreme Court reaffirmed capital punishment. The second-most prolific killer of the condemned is Texas, with 1,322 executions over time. As the busiest of the handful of states that still execute people, Texas could eventually surpass Virginia on that all-time list of shame.

And yes, itâs a bit odd that a freshly purple state like Virginia could be on the verge of such a historic step while California â among the bluest of the blue states â has fallen short, most recently in 2016 when voters approved Proposition 66 to not only retain the death penalty but to truncate the appeal process.

But Proposition 66 did not fully anticipate how to do that; it did not include funding for an expanded capital defense bar to handle the increased caseload, for instance. Then, before any executions could take place, Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a moratorium two years ago, abandoned the single-drug lethal injection protocol and dismantled the death chamber at San Quentin.

A bill to once again put a death penalty ban before voters has been introduced in Sacramento, but so far no action has been taken.

Advocates for capital punishment frame their arguments in terms of justice for victims and executions as deterrents for others who might kill. But the flaws of the system itself overwhelm those points.

Ensuring that the innocent are not wrongly executed â and there is no guarantee â requires a slow and deliberate review process that, given budgetary constraints and overloaded courts, takes years, and in some cases decades, to complete, dragging out the agony of the families involved.

And given that only a handful of people are executed each year, there is little justice â no matter how one defines it â delivered. What we get are randomized and arbitrary applications of the death penalty to people who are disproportionately nonwhite, poor and often suffering from severe mental illness â not people placed on a list based on the heinousness of their crimes, the supposed âworst of the worst.â

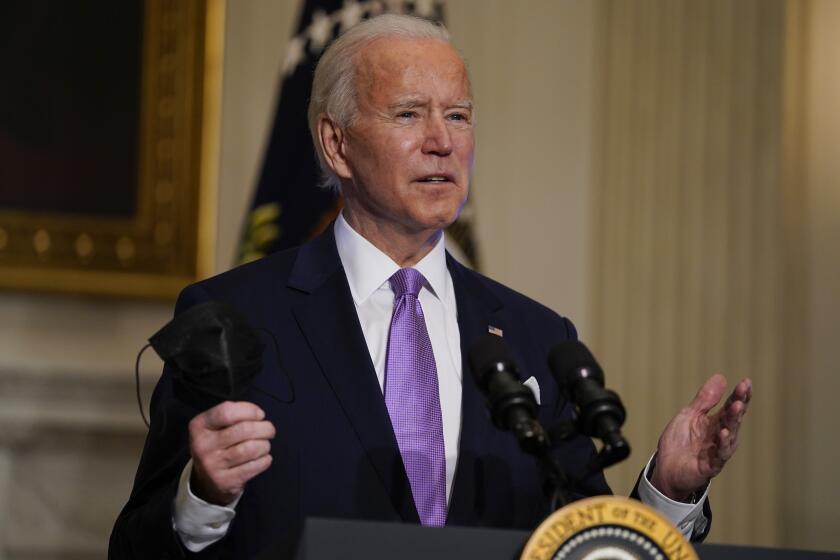

Biden faces a choice on COVID-19 relief: Go small and bipartisan, or go big and potentially pop the unity bubble.

Itâs the racist history of the death penalty that comes into focus with the decision now facing Virginia. The Death Penalty Information Center issued a report last year, âEnduring Injustice: The Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty,â detailing the history of capital punishment in the South from the slave era through the present day.

It includes jarring maps showing the overlap between concentrations of lynchings of Black victims between 1883 and 1940 and state executions of Black defendants from 1972 to 2020. There are many reasons to end the death penalty, but the inherent racism behind how we determine who will die for their crimes stands as the starkest.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.