Op-Ed: COVID-19 may be teaching the world a dangerous lesson: Diseases can be ideal weapons

The devastation COVID-19 has wrought on the U.S. population is staggering. Yet the risks it poses to our national security are also chilling: Diseases are, in many terrible ways, ideal weapons.

Many high-level national security leaders have contracted the virus, including the president. In October most of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and two other high-level military leaders were in quarantine after coming in contact with the vice commandant of the Coast Guard, who tested positive for the disease. A number of White House aides have been infected.

COVID-19 has struck more than 90,000 Department of Defense personnel and their dependents.

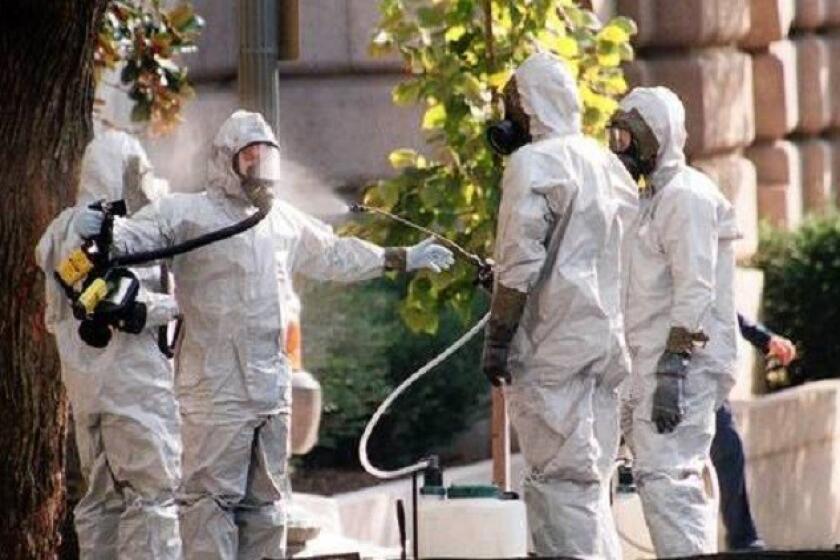

The world has a centuries-long and sad history of deliberate use of diseases in conflict that reaches back to at least 14th century BC when the Hittites sent poisoned animals to their enemies. From the first century onward many militaries tried to spread diseases during conflict using corpses and infected materials like blankets.

The Cold War saw new and frightening feats in the development of biological weapons including by the United States. One major Soviet site could produce 300 metric tons of anthrax agent for use in conflict — more than enough to kill everyone on the planet if deployed effectively.

In the late 20th century, the tide turned, for a time. The Biological Weapons Convention extended international law against bioweapons beginning in the 1970s. Countries cooperated to dismantle Cold War bioweapons programs, including the U.S. collaborating with independent Kazakhstan beginning in the 1990s to eliminate the Soviet anthrax weapons facility.

Yet even before the COVID-19 pandemic, progress against such weapons had eroded. Norms against weapons of mass destruction — usually classified to include nuclear, chemical, biological and radiological weapons — were already growing weaker. In the last decade, Syria, Russia and North Korea repeatedly used chemical weapons. Last summer, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was poisoned with a Soviet-era nerve agent. North Korea’s nuclear weapons testing has driven further proliferation concerns. The United States and Russia are fueling a new nuclear arms race with their respective investments in new nuclear capabilities, and China, India and Pakistan are expanding their arsenals.

These trends could be eclipsed if COVID-19 teaches the world the dangerous lesson that biological weapons are worthy investments.

Here’s what leaders of nations considering biological weapons could be learning. Weaponizing disease could allow them to infiltrate military assets and infect the highest-level leaders of powerful nations. They could cripple economies in a matter of months. They could drive significant disinformation and confusion if countries have to worry that every new outbreak could be an intentional attack.

Unfortunately, the current pandemic shows that easily transmissible diseases may be ideal biological weapons if the aim is to infect as many people as possible, even if that approach endangers the aggressors’ own population.

Diseases also make for cheaper weapons of mass effect than nuclear weapons. There is great fear that post-pandemic, bad actors will view biological weapons as a cost-effective path to disruption and power. U.S. national security agencies are already studying this concern.

The Department of Homeland Security stored sensitive data from BioWatch on an insecure website where it was vulnerable to attacks by hackers, records show.

While getting the current pandemic under control, the Biden administration should aim to deter biological weapons by stripping them of their potential for causing such devastating damage. The United States could do this by creating a system of enhanced preparedness, early warning and rapid response so strong that any infectious diseases that emerge — regardless of whether they stem from nature or a deliberate attack — can be detected and stopped before triggering large-scale outbreaks.

Such a system is technologically feasible. It also could drive significant economic growth if the U.S. devises a strong disease-defense system before other countries do.

Some of the necessary elements are already in place in response to COVID-19. After China posted the coronavirus’ genetic sequence in January, it took only days for companies to use it to build prototype diagnostics, treatments and vaccines. The United States has started expanding technologies that allow quick design and manufacture of therapeutics and vaccines when novel viruses emerge, regardless of the specific pathogen. The speed has quickened on vaccine development during the COVID-19 era — drugmaker Pfizer just announced promising data that could make its vaccine one of the earliest to market in the U.S. We are seeing how the economy can flex to address a biological crisis, including in academic and private labs shifting their assets to ramp up testing.

Wherever possible, the billions of dollars the country invests in COVID-19 responses should be designed to become part of this preparedness and rapid-response ecosystem. For example, it appears that some of the new government-funded vaccine development and manufacturing methods will succeed; the U.S. must maintain and expand these capabilities. This will be critical to persuading those tempted to use biological weapons not to go down that path.

The Pentagon also needs to make dealing with potential biological threats a top priority. America’s defense enterprise includes world-class military medicine experts, brilliant scientists and infrastructure to develop, test and deploy the systems needed to prevent or address biological attacks. Optimizing defense spending against biological threats is a critical complement to augmenting resources for civilian health agencies.

There are simple truths that must guide the Biden team in the months ahead. Even if the administration does all it can to end the pandemic, COVID-19 will make biological weapons seem more attractive than they have been in decades. And the nation will not be secure without creating early-warning and rapid-response systems that halt all biological threats early and effectively.

Christine Parthemore is chief executive officer of the Council on Strategic Risks. Previously, she was a senior advisor for countering weapons of mass destruction at the Pentagon. @CLParthemore

Andy Weber is a senior fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks and a former assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical and biological defense programs. @AndyWeberNCB

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.