Op-Ed: Ramadan in the time of the coronavirus

- Share via

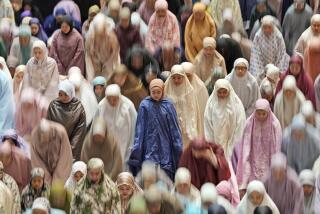

The harira soup was flavored with lamb, the bread was freshly baked, and the dates were sweet as molasses, but what I remember most was the warmth of my parents and siblings around me. In Morocco, as elsewhere in the Muslim world, Ramadan was a time for community. For thirty days, no matter what obligations awaited, my family gathered around the table at sunset, waiting for the muezzin’s call, which signaled the end of the fast. Then, after the iftar meal, it was time to call on friends and neighbors or go to mosque for taraweeh prayers.

After I left home for college and moved to the United States, these childhood memories grew more precious, enhanced as they were by nostalgia. Ramadan remained my favorite holiday, celebrated without fail everywhere I’ve lived. With the spread of the coronavirus, however, the holy month will be unlike any I have ever known. Stay-at-home orders have been imposed around the world. Mosques in many states, including here in California, are closed. There will be no congregational prayers, no visits to family and no nighttime festivities.

Still, this extraordinary time has something to teach us, if only we let it. The solitude that social distancing has suddenly forced upon the faithful gives us an opportunity to reflect on the core principles of Ramadan. According to Islamic tradition, it was during Ramadan that the prophet Muhammad received his spiritual revelation, in the form of the Quran.

It is a month of daily fasting, prayer and reflection, though these are often matched by nightly banqueting, social mingling and partying. Not this year, of course. But freed of its ostentatious parts, Ramadan can better reveal the value of abnegation, charity and solidarity.

Fasting from dawn to dusk gives Muslims the chance to experience in the flesh the deprivation that the needy endure every day. Hunger is a compelling teacher. This year, I have donated more to food pantries, which have been overwhelmed with demand since schools and businesses were shuttered. With unemployment reaching levels not seen since the Great Depression, food pantries will continue to need donations in the months ahead.

Being confined in my home all day has also renewed my commitment to end the cash bail system. Every year in this country, tens of thousands of people are locked up in jail not because they have been convicted of a crime, but because they cannot afford to pay their bail while they wait for their cases to be heard. A bail-fund contribution was already on my charity list, but with the spread of a highly infectious virus it was even more urgent.

In our “Dispatches From the Pandemic” series, we bring you personal stories from people whose lives have been altered by COVID-19.

And while the quarantine prevents me from hosting elaborate iftars with family and friends, spending so much time with my husband and daughter has been enriching in other ways. It has given me the chance to reflect on the migrants and refugees who were separated from their children at the border. Since the president’s family separation policy was enacted in 2018, their stories have slowly faded from the headlines.

Aside from donating to various relief agencies, I’ve also found myself looking for ways to express my gratitude to those who risk their lives to make sheltering in place possible for the rest of us — grocery store clerks, truck drivers, delivery workers, mail carriers, healthcare workers, among many others. These may be small gestures, like posting a thank you note on my door or leaving a generous tip through a delivery app, but they are what I can do while maintaining safe physical distancing.

The biggest challenge for me is to remain hopeful in the face of devastation. More than 53,000 Americans are dead and tens of millions have lost their livelihoods. Meanwhile, the president muses about injecting disinfectant and, as usual, rails against the press. But here too, the holy month has been a salve, as it has reminded me that “with every hardship, there is relief.” (Quran, 94:6.)

“Have you ever experienced anything like this?” I asked my father, who turned 83 years old recently. “Never,” he replied.

In Morocco, where he and my mother live, quarantine restrictions are far more stringent than those in California, where I live. Only one person can leave the house to do the groceries, and they must carry a laissez-passer than can be checked by the police. There is a curfew in place after 7 p.m.

I think about what my parents had survived — World War II, foreign occupation, political unrest, multiple droughts and emergencies of all kinds — and I think we will survive this, too. Inshallah.

Laila Lalami is the author of “The Other Americans,” a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.