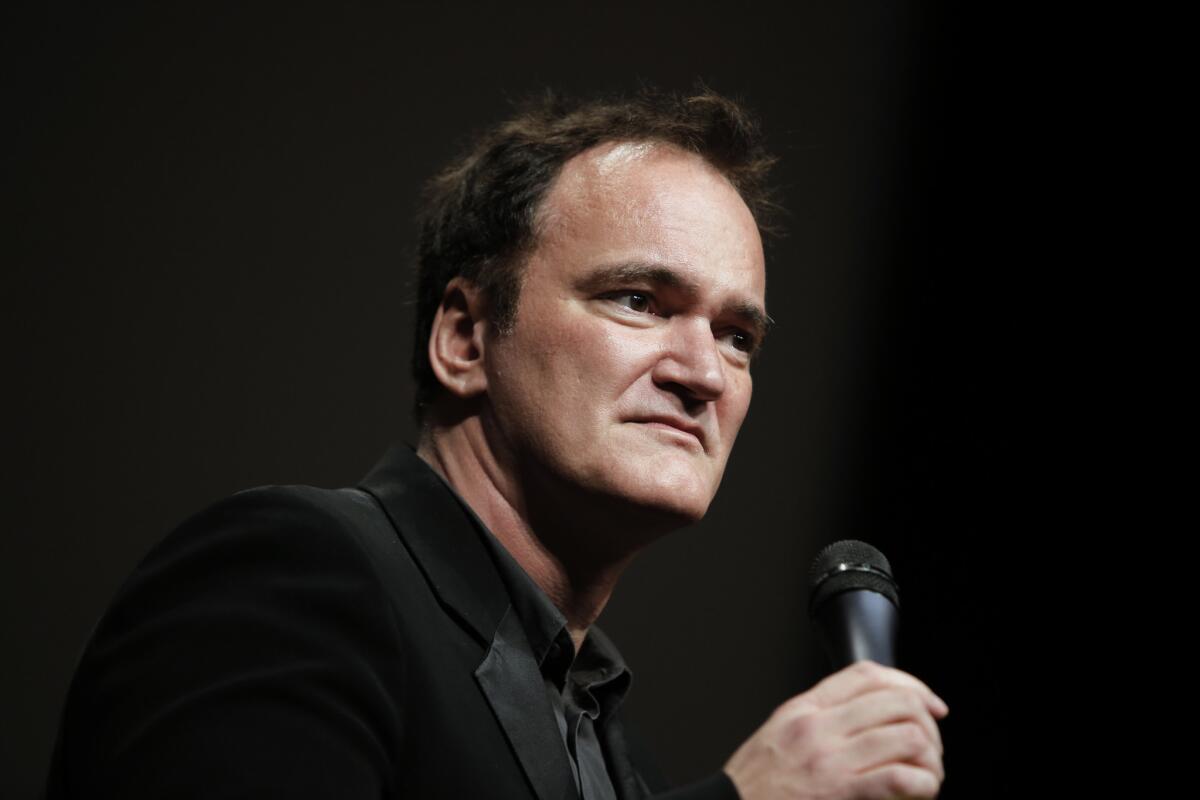

Tarantino vs. Gawker: When is linking illegal for journalists?

Gawkerâs stock in trade is revealing things about celebrities and other public figures that theyâd much rather keep private. And as long as what it prints is true, itâs pretty much immune from libel lawsuits.

Not so for copyright infringement, though. And though Gawker isnât the most sympathetic outlet, a new lawsuit against the site for linking to an infringing copy of an unreleased screenplay should send chills down the spines of every reporter who writes about copyright issues.

On Thursday, the Gawker Media site Defamer published an article titled âHere Is the Leaked Quentin Tarantino Hateful Eight Script,â about the filmmakerâs latest project. Tarantino had kept the script unpublished, but someone obtained a copy and posted it online. In the piece, Defamer quoted only a brief excerpt and a short summary published earlier that day by the Wrap. But it also included two links to the leaked screenplay on a file-sharing site called AnonFiles.

You might be thinking at this point that including the links was unnecessary and damaging to Tarantino. The ânewsâ in this episode was the fact that the screenplay had been leaked and that, as a consequence, Tarantino had decided not to make the film for now.

But that revelation was already all over the Web; the website Deadline had broken that story the previous Tuesday. So Deadlineâs competitors were left to look for new angles. To the extent the Defamer post moved the news needle at all, it was by providing a way for the public to see what the fuss was all about.

Which is not to say that what Defamer did was legal. But reporters often assume that providing links to items of public interest is perfectly aboveboard, even if the items themselves arenât. If this case goes to trial, it could help clarify what links simply canât be published legally, regardless of the news value.

The lawyers I consulted, including The Timesâ Jeff Glasser, couldnât think of any cases in which a news site had been sued for publishing a link to infringing content someone else had posted. But attorney Michael Page, a copyright expert at Durie Tangri in San Francisco, said providing such a link could nevertheless amount to âcontributoryâ infringement, particularly when the news site had been told the material was infringing and yet refused to delete it.

In a complaint filed Monday in federal court in Los Angeles, Tarantinoâs lawyers say they repeatedly asked Gawker Media to remove the links, to no avail. In fact, they allege that Defamer updated the post on Sunday to add a link to another copy of the screenplay that had been posted on the site Scribd.

(You can see a copy of the complaint that the Hollywood Reporterâs Eriq Gardner posted here. Gardnerâs take on the case is here.)

Page -- who represented the file-sharing network Grokster in its epic legal battle against the entertainment industry and so has some experience with this sort of thing -- said Gawker may put forward a fair-use defense, but thatâs hurt by the nature of the linked item. Itâs hard to argue that posting the entire, unpublished script was a fair use, Page said.

Tarantinoâs complaint relies heavily on the inducement doctrine the Supreme Court laid out in its 2004 Grokster ruling. It argues that the Defamer story not only made it easy for the general public to read a leaked script that previously had been hard to find online, but also that it encouraged people to do so.

John Cook, Gawkerâs editor, responded Monday with a post that rebuts the complaintâs most damaging allegations, saying Defamer had no involvement whatsoever in the leak or the scriptâs posting online. He also quotes Tarantinoâs comments last week to Deadline Hollywood, in which the filmmaker said he likes having his work online for people to read and review.

Writing about a copyright dispute, especially when the subject is a work that leaked before publication, is a sensitive business. For a major work, you can count on the copyright owner to sue the leaker and the site that makes the pirated copy available; Tarantinoâs complaint also seeks damages from AnonFiles and a number of unidentified individuals who helped put the script online. Yet the fact of the leak is just part of the story; so is what was leaked.

Page argued that Gawker would have been on safer ground had it published an excerpt from the script rather than pointing readers to where to find it. Yet once youâve published an excerpt, the next question from readers is, âWhat about the rest of it?â

Again, Iâm not arguing that what Gawker did was legal -- thatâs a judgeâs decision. Iâm just saying that thereâs a journalistic reason for Gawker to do what it did, and those of us who write about copyrights struggle often with the question of how to report what seems newsworthy without crossing a line thatâs drawn case by case.

ALSO:

Californiaâs drought, times three

Harry Reid earns an assist on Iran

Protect good teachers, fire bad ones

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey and Google+

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.