Opinion: Was the Malheur occupation legal, or did the feds botch the Bundy case?

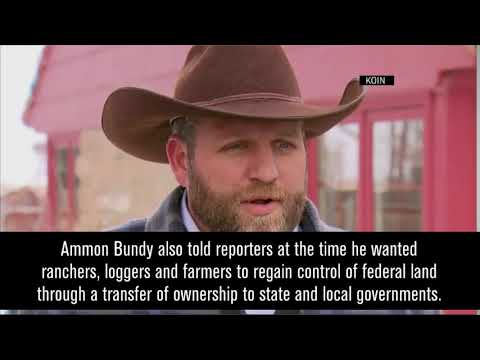

Ammon and Ryan Bundy, and five others had been charged with conspiracy to prevent federal employees from doing their jobs by occupying the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge for 41 days in Oregon in early 2016.

- Share via

The acquittal Thursday of seven anti-government activists who occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon for six weeks last winter was stunning. Armed and angry, the activists seized the property to protest imprisonment of two ranchers convicted of setting fires that spread to federal land. The protest quickly blossomed into a challenge of the federal government’s right to federal land, during which the occupiers blatantly violated laws against possessing firearms in such a facility.

That’s not a theory cooked up by a prosecutor. The seven defendants acknowledged in court that that was exactly what they had done. During the occupation, they appeared in news photos with firearms plainly visible, shot off rounds at the compound, and some vowed to fight if federal agents sought to regain control of the federal facility. Eleven others involved in the takeover have already pleaded guilty.

Yet a jury found brothers Ammon and Ryan Bundy and five others not guilty of conspiracy charges arising from the occupation. Though as one juror is reported to have said, that doesn’t mean the jury found them innocent. The problem, the juror said, was the federal prosecutor failed to make the case that what occurred at the wildlife refuge was, indeed, a conspiracy, as it charged.

As one juror is reported to have said, that doesn’t mean the jury found them innocent.

“It should be known that all 12 jurors felt that this verdict was a statement regarding the various failures of the prosecution to prove ‘conspiracy’ in the count itself – and not any form of affirmation of the defense’s various beliefs, actions or aspirations,” the anonymous juror told the Oregonian in an email, adding that after the verdict was read the jurors met with the judge and pressed her on why the prosecution went the conspiracy route in the first place.

Because, the juror said they were told, it would have resulted in the toughest sentence.

“We were not asked to judge on bullets and hurt feelings, rather to decide if any agreement was made with an illegal object in mind,” the juror wrote. “It seemed this basic, high standard of proof was lost upon the prosecution throughout.”

In fact, the juror suggested, the government was overconfident in its case.

“The air of triumphalism that the prosecution brought was not lost on any of us,” the juror wrote, “nor was it warranted given their burden of proof.”

So was it a botched prosecution? Maybe. In fact, that would be a better explanation than to discover that a jury looked at clear-cut evidence, including confessions by the perpetrators, of an armed takeover and standoff on federal land and determined that such actions do not constitute a crime.

It’s unclear what the fallout from the debacle will be, particularly given its timing in the midst of a presidential election that taps into an undercurrent of anti-government sentiments. And in an unrelated showdown, armed law-enforcement officers have been clearing and arresting mostly Native American protesters occupying private land in North Dakota over which a controversial oil pipeline is being built.

Different issues were involved than at Malheur than in North Dakota, but the concurrence is jarring: A white jury acquits white anti-government protesters of seizing federal land at the same time authorities arrest more than 140 Native Americans trying to block a pipeline across private land that the protesters claim rightfully belongs to Native Americans under an 1851 treaty.

So will the anti-government activists find the Oregon acquittal emboldening and try more occupations? Let’s hope not. In the short term, some of the key leaders, including the Bundy brothers, remain locked up ahead of a trial in Nevada on charges related to another armed standoff over unpaid federal grazing fees owed by Cliven Bundy, their father. So some of the movement participants might still be held to account

But at the very least, the verdict should remind the U.S. Justice Department that a case, and a conspiracy, that might seem obvious to a prosecutor isn’t necessarily obvious to a jury. That’s an important lesson as the government heads to court once again.

Follow my posts and re-tweets at @smartelle on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.