Op-Ed: That wasnât a âtown hallâ debate

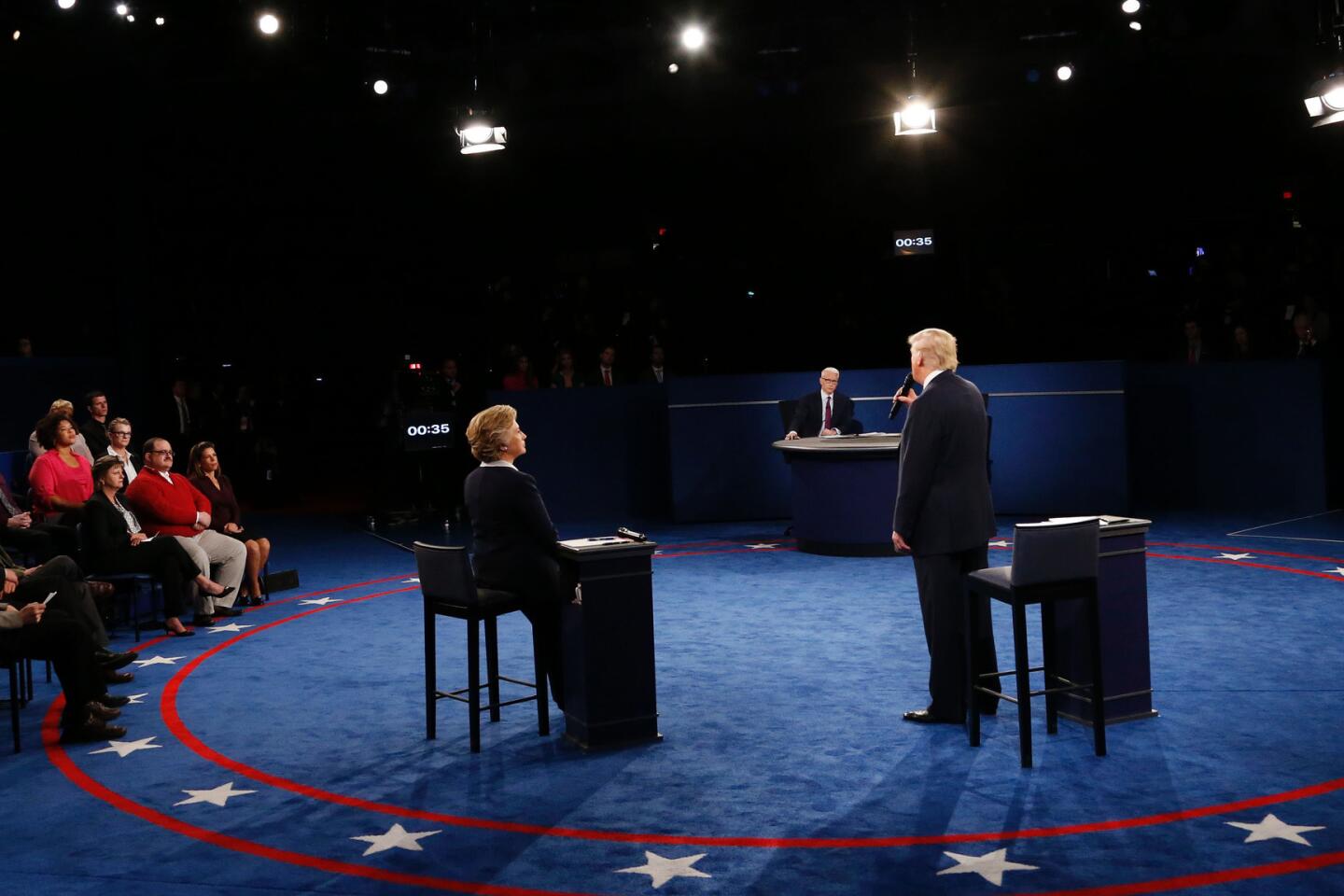

After watching Sundayâs 90-minute made-for-TV docu-drama, dripping with the venom of âHouse of Cardsâ and the guile of âUnREAL,â one thing is certain: We need to stop calling this format the âtown hallâ debate.

âTown hallâ evokes the meetings used in Puritan New England to adjudicate matters of local governance. Itâs meant to, of course. Both the typical 17th-century town meeting of, say, my hometown of Springfield, Mass., and the presidential-debate spectacle in St. Louis on Sunday night feature large audiences of unelected people from the area, simple townsfolk, who speak up as well as listen.

The careful deliberation and direct democracy of the town meeting represent, for many, the kind of simple virtues that we could have in politics today, if only (pick one) we got big money out, or got rid of lobbyists, or had a more robust media. The town hall is the format of populist hopefulness. Leave the questioning to the common folk. With their good sense, theyâll ask the straightforward questions that slick media folk let slick politicians dodge.

From the beginning, however, the format has failed to live up to its namesake.

âTonightâs program is unlike any other presidential debate in history,â ABCâs Carole Simpson said, on Oct. 15, 1992, as she introduced the first town hall debate, with â209 uncommitted votersâ behind her. âThe candidates [Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot] will be asked questions by these voters on a topic of their choosing â anything they want to ask about.â

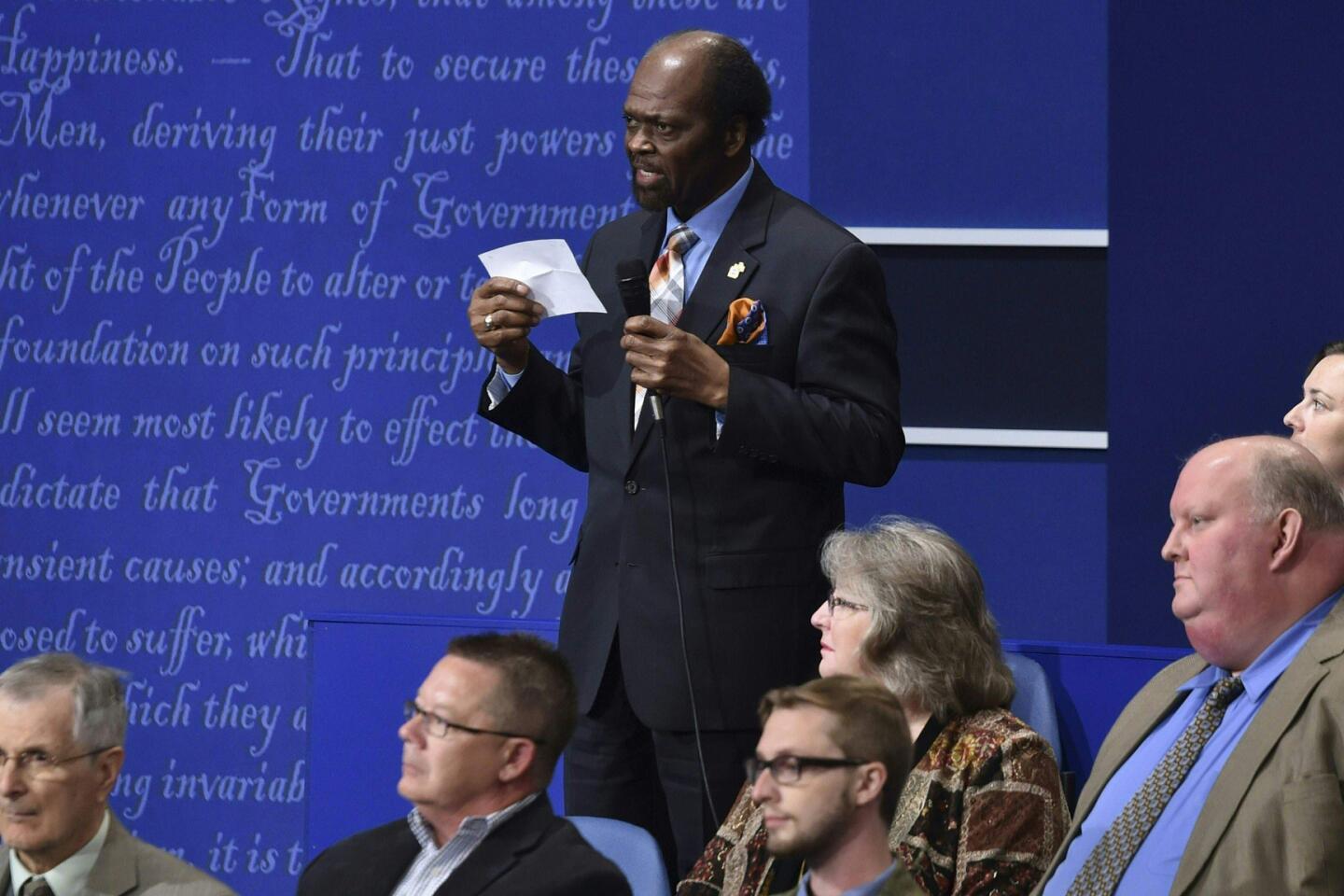

Yet watching tape of that debate, the audience questions were as plodding, and almost as non-specific, then as they were on Sunday night. In 1992, we got one man rising to ask, âHow can we as, symbolically, the children of the future president, expect the three of you to meet our needs?â Sunday night, an audience member asked: âMy question is, do you believe you can be a devoted president to all the people in the United States?â

We love the idea of New England town meetings because, we believe, they empowered the people. But in presidential politics, the town hall debate format does the opposite: it infantilizes the people, reducing them to children. Note how, in the case above, the questioner even calls the electorate âchildrenâ â asking benevolent moms and dads how their needs will be met.

In the old town meetings, any voter (which meant only men, sometimes only property-holding men) could speak, on matters of taxes, budgeting and so forth. At the end, the voters got to vote. There was an incentive to discuss policy, in a serious way, because policy was made there.

In the current town hall debate format, the only incentive is to give people-pleasing answers, because the candidates have to appear both likable to viewers at home and empathetic to the questioners in the audience.

The town hall format was probably inevitable, for a number of reasons.

For one thing, in those very early Internet days, the idea of mass, crowd-sourced democracy was in the air. In the 1992 debate, you can hear Perot talk about the âelectronic town hallsâ he would hold if elected.

And given how much the public knew about the candidatesâ private lives in the era of tabloid TV â which had, after all, taken down candidate Gary Hart the previous campaign cycle â it was only a matter of time before candidates realized that they had been forcibly taken off their pedestals. They couldnât maintain a cool distance any longer. Once a candidate had made time to play saxophone on Arsenio Hallâs late-night show, as Clinton had in June, it was probably time to let the voters into the debates.

The most important influence on the format, however, was surely the daytime talk show, which in the 1980s had moved beyond the traditional desk-and-sofa late-night format by inviting audience questions.

Phil Donahue was the first roving host, bounding up stairs and climbing over people to get his microphone to audience members. His show went national in 1970, and by 1992 imitators were all over the airwaves, including Sally Jessy Raphael and Geraldo Rivera. In 1986, Oprah Winfrey went national, and she almost immediately displaced Donahue as the top-rated host.

Itâs these shows, more than the original town meetings, that were in the air on Sunday night.

Which brings me back to my original point. If we donât drop the format, letâs at least drop the âtown hallâ label. Town Hall Debate? Try the Donahue Dialogue. Or maybe just The Springer.

Mark Oppenheimer is a contributing writer to Opinion.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

ALSO

Op-Ed: The time Donald Trump wrote me a thank-you note

Editorial: At long last, Republican leaders must disavow Trump

Op-Ed: It takes a village to raise a misogynistic monster like Donald Trump

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.