Op-Ed: California’s ‘jungle’ primary system could blow up in the Democratic Party’s face

- Share via

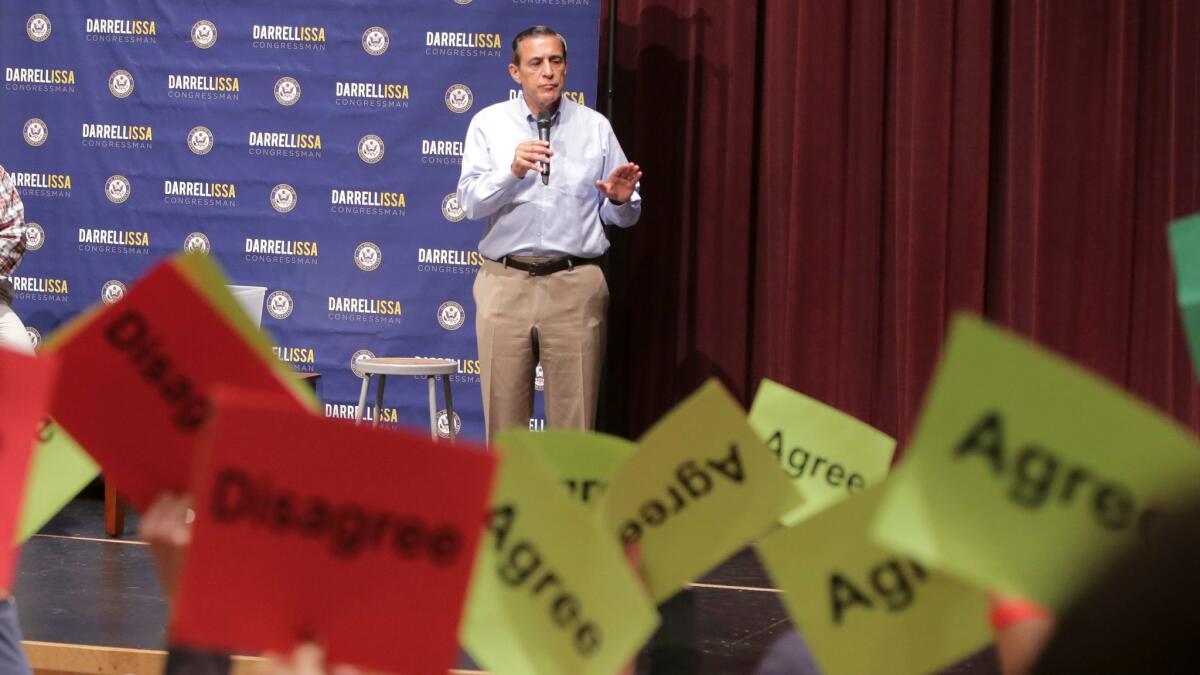

When two Orange County Republican congressmen — Ed Royce and Darrell Issa, both of whom were facing tough races this November— declared earlier this month that they wouldn’t seek re-election, Democrats were elated. Without an incumbent on the ballot, they believed, one of the many Democrat challengers who’d already declared their candidacies would surely emerge victorious in each district.

Well, maybe. There’s a wild card in this electoral deck that renders those outcomes uncertain, and it’s not just President Trump’s popularity or the state of the economy. It’s the structure of California elections: more precisely, our crazy “jungle” primary.

Under our newish electoral system, the top two finishers in the primary election, regardless of party affiliation, run against each other in November. Because California has become so overwhelmingly a Democratic state, the full effect of our jungle primary has not yet been felt. A Democrat wins statewide office either by defeating a Republican in November or — if Democrats place one-two in the primary — by ensuring that no Republican appears on the November ballot at all. (The referendum that established the jungle primary also eliminated the possibility of November write-in candidates.)

But what will happen when multiple candidates of both major parties seek office in a swing district? That’s exactly what’s shaping up in the contests to replace Royce and Issa.

In Issa’s district, three Democratic candidates have already raised more than $500,000 each. And in the weeks since Issa announced his bow-out, a host of Republican candidates have come forward, too, including one state Assembly member, one former Assembly member, and a county supervisor. In Royce’s district, three Democrats have raised more than $600,000 each, while on the Republican side, a former state senator, a former state Assembly member and a county supervisor have also entered the fray. In both districts, other Democrats and Republicans are also running, and more may yet enter.

Here’s where the jungle primary enters the picture.

Suppose — and it’s anything but a wild supposition — that the Koch brothers funding network, or some other group of mega-rich donors, decides to fund two Republicans in each of those races, giving those candidates a decided advantage. Suppose the three leading Democrats in each of those races stay in the race, along with the other Democrats still in the field. (There are seven Democratic candidates in Royce’s district.) Suppose, in the June primary, the total vote for the district’s Republican candidates comes to 44%, with the two leaders each winning 20%. Suppose the total vote for the district’s Democratic candidates comes to 54% (let’s say 2% goes to minor party candidates), but it’s split so many ways that the leading Democrat gets just 19%.

The activists who’ve powered the resistance must find a way to come together in support of one or two candidates.

If all those suppositions hold, then the candidates in the November run-off would both be Republicans, even though the Democrats would have collectively outpolled the GOP hopefuls by 10 percentage points.

How far-fetched is this hypothetical? Given that control of the House is shaping up as a huge national battle, with Orange County as its epicenter, it requires no imaginative leap to see the Kochs or their equivalents gaming the system in just this manner.

The Democrats are generally a more unruly bunch when it comes to candidate selection. And this year, with so many candidates coming out of the woodwork, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, at least in California, appears to have an uncharacteristic hands-off policy. Given the suspicions that many progressive activists harbor toward the DCCC, which has often favored more centrist and self-funding wealthy candidates, that’s a prudent move.

But unless Democrats want to sacrifice potential congressional pick-ups to the vagaries of the jungle primary, they need to devise a winnowing process of their own. Perforce, that duty falls to the activist groups in each of the districts: Indivisible, abortion-rights groups, unions, civil and immigrant rights organizations, Our Revolution, Democratic clubs and so on. Somehow, in a process that’s bound to be messy, the activists who’ve powered the resistance must find a way to come together in support of one or two candidates, and campaign for them as fervently and consistently as they have campaigned against Trump.

Agreeing on a candidate is a lot more complicated than agreeing on the slogans for a march, but to move from resisting policy to making policy, that’s what Democrats — forced to compete under the law of the jungle — will have to do.

Harold Meyerson is executive editor of American Prospect. He is a contributing writer to Opinion.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.